Using a Gospel Synopsis

Lecture Notes for Topics 1.3 - 1.3.3 in

in

Religion 311

Last revised: 9/02/03

Explanation:

Contained

below is a manuscript summarizing the class lecture(s) covering the above

specified range of topics from the List of Topics for the appropriate course(s)

indicated above: Religion 102

/ 305 / 311 / 314.

For updated information about the class, see the appropriate class bulletin

board: Religion 102

/ 305 / 311 / 314.

Quite often hyperlinks (underlined)

to sources of information etc. will be inserted in the text of the lecture.

Test questions for all quizzes and exams will be derived in their entirety

or in part from these lectures; see Exams

in the appropriate course syllabus for details: Religion

102

/ 305 / 311 / 314.

To

display the Greek text contained in this page download and install the

free BSTGreek

from Bible Study Tools. |

Go Directly to topic:

1.3

What is a

gospel synopsis? |

1.3.1

A Gospel Harmony

and

A Gospel Synopsis |

1.3.2

Types of

Gospel Synopses |

1.3.3

How to Use

a Gospel Synopsis |

Bibliography |

|

1.3 What is a Gospel Synopsis?

When studying the Bible one

occasionally comes across duplicate narratives of the same historical event.

Seldom, if ever, do the duplicate narratives describe the one event the

same way. What could be discovered if these duplicate descriptions were

placed side by side in parallel columns? This was and remains a central

point in the use of a gospel synopsis or gospel harmony. When the double

or triple tradition materials are listed side by side the Bible student

can do a more detailed analysis of the distinctive perspectives of each

gospel writer with much greater efficiency. At a higher technical level,

the use of a gospel synopsis containing the Greek text of the gospels facilitates

the more detailed analysis involved in both Source Criticism and Form Criticism.

This unit of study seeks

to acquaint the student both with the tools and the procedures for using

a gospel synopsis. The discussion is by nature introductory and will not

produce a technical scholar. But, hopefully, a foundation will be laid

for subsequent development of scholarly expertise in this area to whatever

extent your interests carry you in the future.

1.3.1

A Gospel Harmony and A Gospel Synopsis

When checking the titles

of this kind of book, you will quickly notice the occurrence of one of

two words appearing the in book title most of the time. It will be either

'harmony' or 'synopsis.' What is the difference? Actually, at surface glance

you will not notice significant differences. But, when the presuppositions

that are foundational to the organizing structure are examined, then quite

important differences are detected. These will be explored below.

Other Viewpoints:

Robert W. Funk, "Synopses and Harmonies,"

New

Gospel Parallels, vol. one: The Synoptic Gospels (1985), pp. xi-xiii.

In recent gospel synopses, the emphasis has been on the paradigmatic or

vertical dimensions of the gospel materials, as a consequence of the influence

of form criticism and in reaction against older study instruments which

sought to "harmonize" the fourfold canonical tradition. On the other hand,

harmonies, as they are called, endeavor to weave all the elements of the

tradition into a single chronological strand, into one composite order

or sequence. Harmonies are therefore predominantly syntagmatic.1

We may consider, first, the more recent synopses and then return, subsequently,

to the older harmonies.

Synopses were originally created for the microscopic comparison of words

and phrases in parallel texts; a synopsis of this type is oriented primarily

to source criticism. Synopses were later fabricated also for the close

comparison of oral pericopes; this kind of synopsis came into being under

the aegis of form criticism. Redaction criticism eventually made use of

synopses as well, although special synopses seem not to have been created

for that specific purpose.

The first kind of synopsis is concerned with the synoptic problem, that

is, with the problem of the relationships among written sources; the second

type was interested as much or more in the oral prehistory of the materials.

More recent versions of synopses, such as Huck-Greeven and its English

language counterparts, attempt to combine the two interests with increasingly

dubious results.

The two types of synopses betray differing judgments about the character

of the gospel materials.

The synopsis oriented to source criticism was concerned to determine which

of the gospels was chronologically prior and was employed as a source by

the other two synoptic writers. Once the two-source hypothesis (and its

variations) became established, the consensus formed around Mark as the

original written gospel. Matthew and Luke were taken to be dependent on

Mark and another source, now lost, called Q (which stands for the German

word Quelle, meaning source). John dropped out of the picture as

a contender for highest historical honors, and consequently dropped out

of many synopses as well. The function of the source-critical synopsis

then became to show how Matthew and Luke edited Mark in the process of

creating their own gospels: the columnar treatment, which has once served

primarily to demonstrate the priority of Mark, was converted, under redaction

criticism, to the second purpose, now taken to be the more interesting

question.

After the flowering of source criticism and the consensus that consigned

the priority to Mark, but before the advent of redaction criticism form

criticism took the field. Karl Ludwig Schmidt, Martin Dibelius, and Rudolf

Bultmann demonstrated how the written sources of the canonical gospels

were preceded by a significant period of oral creativity and transmission

of the Jesus tradition. If one breaks the written gospels apart at their

editorial seams, clearly demarcated oral units separate themselves from

the editorial dross utilized by the canonical authors to weave the pieces

together into weak narratives. These oral units may be classified according

to form and compared with other units of like form, in the same gospel

and in other gospels. A properly designed synopsis can assist with this

process of paradigmatic comparison. The cohesive editorial material is

of course discarded or given a relatively low value quotient by the form

critics.

The form-critical use of synopses took the oral segments to be relatively

stable and reliable in relation to the rest of the material; it placed

little or no value on the narrative sequences in each of the gospels.

The older interest of synopses in source criticism perpetuated a certain

interest in sequence, particularly in Mark, although here, too, the synopsis

was obviously more concerned with vertical comparison of words and phrases

than with order or chronology.

The gospel harmony, on the other hand, lacks a genuine interest in the

differences revealed by paradigmatic study; its concern is to smooth the

versions out and work them up into one sequence. The resulting sequence,

of course, was entirely arbitrary: there were as many sequences as there

were harmony editors, and none of them was congruent with the sequence

presented by one of the evangelists.

When the harmony was generally discredited, interest in sequence collapsed.

That is to be regretted, although it is not to be regretted that the harmonizing

strategy was abandoned. Nevertheless, sequence is an important feature

of narrative and cannot be ignored in any serious study of narrative, gospel

or other. The paradigmatic study of the gospels was subsequently challenged

as well, but without decisive results. A renewed interest in biblical narrative,

especially on the part of literary critics, has nevertheless served to

infringe the domination of source, form, and redaction criticism, and thus

of the paradigmatic. This new interest and its impact suggest that gospel

criticism is going through a transitional stage. It is probably correct

to say that the balance between the paradigmatic and the syntagmatic is

being restored.

The restoration of balance between the paradigmatic and the syntagmatic

signals a new phase of gospel criticism. The paradigmatic study of the

gospel materials will no longer be motivated primarily by the interests

of form criticism, with its more or less overriding concern to establish

the oral history of the units of material. Instead, associative comparison

will range over a much broader spectrum of material -- miracle stories,

pronouncement stories, chreia, parables, aphorisms drawn from all

over the hellenistic world. The new aim will be to learn as much as possible

about how these particular linguistic vehicles, rather than some other

types of discourse, came to be employed as building blocks of the gospels.

The syntagmatic study of the gospels will not be concerned to recover or

reconstruct the historical chain of events lying behind the gospels --

which are, in any case, simply beyond reach, given our present sources

-- but will take an interest in the gospel narratives in and of themselves.

Narrative is a form od discourse having its own grammar; as such, narrative

is a linguistic screen through which the story of Jesus must pass. By examining

that screen closely, we may learn why the first raconteurs elected to narrate

the things they did, in the way they did. We will certainly learn something

of the rules to which they had to subscribe in narrating anything at all.

We will do this, in this first instance, because the gospel narratives

are, in fact, all we have; we may wish to make as much of them as possible.

The combination of paradigmatic and syntagmatic research in their new forms

will open up new horizons in understanding the gospel narratives. The New

Gospel Parallels is designed to make many other uses possible, some

or many of which cannot be forecast.

----------

1David Dungan,

"Theory of Synopsis Construction," Biblica 61 (1980) 305-29, gives

definitions of the "harmony" and the "synopsis" (310) which are adopted

here. Dungan's analysis of the issues connected with synopsis construction

and his constructive proposals are worth careful study. However, his views

suffer from a narrow orientation to the synoptic problem and the question

of gospel priority. These questions need not be permitted to tyrannize

the design of a study instrument.

1.3.1.1 Harmony

The gospel harmony by definition

attempts to harmonize the gospel accounts of the life and teaching of Jesus

into a chronological framework beginning with his birth and ending with

his ascension to Heaven. A chronological framework is developed using the

four canonical gospels. But what basis can be used for this framework?

As Robertson (below) points out, early harmonies in the modern era used

the feasts described in the four gospels as hinge points and thus developed

their framework around these references to Jewish feasts. But toward the

end of the 1800s with advancements in Source Criticism, a new framework

was developed, beginning with Broadus (1893), Stevens and Burton (1893)

et als. The older assumption of being able to develop a precise chronological

framework for the various pericopes in the synoptic gospels began fading

to be replaced with more modest historical assumptions.

Yet, the issue of the legitimacy

of a gospel harmony remains important, especially in evangelical Christian

circles. This because of the historical nature of the Christian religion,

and because of the issue of the historical

Jesus. The emergence of Historical

Criticism at the beginning of the modern era of western culture has

demonstrated the importance of these aspects. When very positive conclusions

are reached about both these issues, then the next step is to attempt to

reconstruct some kind of chronological framework for the life and ministry

of Jesus of Nazareth. To be certain, modern critical studies have clearly

demonstrated the immense challenges involved in such an effort. But, large

hurdles to clear doesn't mean that we refuse to try to find ways over them.

The conclusions reached

here will powerfully dictate some of the structure details in setting up

a harmony, or a synopsis. I do concur with the viewpoint that a harmony

in the strict definition of the term is impossible, given the limited data

available from both the canonical gospels and from other ancient sources.

But, one can develop a broad chronological framework and then develop a

text formatting process that allows for the variations etc. that come when

treating the scripture texts.

Other Viewpoints:

A.T. Robertson, "About Harmonies of the Gospels,"

A

Harmony of the Gospels, (1922) pp. 253-254:

We do not know how soon an effort was made to combine in one book the several

portrayals of the life of Jesus. Luke in his Gospel (1:1-4) makes a selection

of the material and incorporates data from different sources, but with

the stamp o his own arrangement and style. He followed, in the main, the

order of Mark's Gospel, as is easily seen. But this method is not what

is meant by a harmony of the Gospels, for the result is a selection from

all sorts of material (oral and written), monographs and longer treatises.

The first know harmony is Tatian's Diatessaron (dia tessaron, by

four) in the second century (about 160 A.D.) in the Syriac tongue. It was

long lost, but an Arabic translation has been found and an English rendering

appeared in 1894 by J. Hamlyn Hill. It is plain that Tatian has blended

into one narrative our Four Gospels with a certain amount of freedom as

is show by Hobson's The Diatessaron of Tatian and the Synoptic Problem

(1904). There have been modern attempts also to combine into one story

the records of the Four Gospels. There is a superficial advantage in such

an effort in the freedom from variations in the accounts, but the loss

is too great for such an arbitrary gain. The word harmony calls for such

an arrangement, but it is not the method of the best modern harmonies which

preserve the differences in material and style just as they are in the

Four Gospels.

In the third century Ammonius arranged the Gospels in four parallel columns

(the Sections of Ammonius). This was an attempt to give a conspectus

of the material in the Gospels side by side. In the fourth century Eusebius

with his Canons and Sections enabled the reader to see at

a glance the parallel passages in the Gospels. The ancients took a keen

interest in this form of study of the Gospels, as Augustine shows.

Of modern harmonies that by Edward Robinson has had the most influence.

The edition in English appeared in 1845, that in Greek in 1846. Riddle

revised Robinson's Harmony in 1889. There were many others that employed

the Authorized Version, like Clark's and that divided the life of Christ

according to the feasts.

Broadus (June, 1893) followed Waddy (1887) in the use of the Canterbury

Revision, but was the first to break away from the division by feasts and

to [p.254] show the historical development in the life of Jesus. Stevens

and Burton followed (December, 1893) Broadus within six months and, like

him, used the Canterbury Revision and had an independent division of the

life of Christ to show the historical unfolding of the events. These two

harmonies have held the field for nearly thirty years for students of the

English Gospels. In 1903 Kerr issued one in the American Standard Version

and James one in the Canterbury Revision (1901).

Harmonies of the Gospels in the Greek continued to appear, like Tischendorf's

(1851, new edition 1891), Wright's A Synopsis of the Gospels in Greek

(1903), Huck's Synopsis der drei ersten Evangelien (1892, English

translation in 1907), Campbell's First Three Gospels in Greek (1899),

A

Harmony of the Synoptic Gospels in Greek by Burton and Goodspeed (1920).

The progress in synoptic criticism emphasized the difference in subject

matter and style between the Synoptic Gospels and the Fourth Gospel as

appears in the works of Huck, Campbell, and Burton and Goodspeed that give

only the Synoptic Gospels. Burton and Goodspeed have also an English work,

A

Harmony of the Synoptic Gospels for Historical and Critical Study (1917).

In 1917 Sharman (Records of the Life of Jesus) gives first a harmony

of the Synoptic Gospels with references to the Fourth Gospel and then an

outline of the Fourth Gospel with references to the Synoptic Gospels.

Once more in 1919 Van Kirk produced The Source Book of the Life of Christ

which is only a partial harmony, for the parables and speeches of Jesus

are only referred to, not quoted. But he endeavored to show the results

of Gospel criticism in the text of the book. There is much useful material

here for a harmony, but it is not a real harmony that can be used for the

full story of the life of Jesus. Van Kirk, however, is the first writer

to place Mark in the first column instead of Matthew. I had already done

it in my outline before I say Van Kirk's book, but his was published first.

It is an immense improvement to put Mark first. The student thus sees that

the arrangement of the material is not arbitrary and whimsical, but orderly

and natural. Both Matthew and Luke follow Mark's order except in the first

part of Matthew where he is topical in the main. John supplements the Synoptic

Gospels, particularly in the Judean (Jerusalem) Ministry.

Slowly, therefore, progress has been made in the harmonies of the Gospels.

But the modern student is able to reproduce the life and words of Jesus

as has not been possible since the first century. It is a fourfold portrait

of Christ that we get, but the whole is infinitely richer than the picture

given by any one of the Four Gospels. The present Harmony aims to put the

student in touch with the results of modern scholarly research and to focus

attention on the actual story in the Gospels themselves. One may have his

own opinion of the Fourth Gospel, but it is needed in a harmony for completeness.

Robert L. Thomas and Stanley

N. Gundry, "Preface to the 1988 Revision," The NIV Harmony of the Gospels

with Explanations and Essays, (1988), pp. 5-7.

The roots of this Harmony extend deep into the soil of nineteenth-century

biblical scholarship. The renowned John A. Broadus began teaching the life

of Jesus in 1859. At the suggestion of his colleague A.T. Robertson, in

1893 he published the fruit of these thirty-plus years of instruction.

Robertson himself began offering the same course in 1888, and after thirty-four

years published his own Harmony, which was a revision of Broadus's

first edition and had published a minor revision of Broadus's work in 1903.

This lineage of gospel harmonies has gone through many printings and has

been a powerful force in the church of Jesus Christ through the decades

of the twentieth century.

One of the reasons for this widespread influence is that Broadus blazed

a trail that has been followed by many twentieth-century harmonists. Rather

than trying to force an issue and make the feasts into turning points in

Christ's ministry, as had his predecessors, he organized Jesus' ministry

into well-defined periods according to a gradual progress in three realms:

in Jesus' self-manifestation, in the hostility of his enemies, and in the

training of the Twelve. This new approach, as Broadus noted in his preface

in 1893, facilitated an understanding of "the inner movement of the history,

towards that long-delayed, but foreseen and inevitable collision, in which,

beyond all other instances, the wrath of man was made to praise God."

Robertson built upon Broadus's successful endeavor with his 1922 revision

by refining, expanding, and updating the work of his former mentor. It

is the purpose of this 1988 revision to build upon Robertson's revision

and fine tune the work even more in the light of more than six decades

of Christian thought that have passed since the popular revision was first

published.

The current work, for one thing, attempts a greater precision in defining

the "inner movements" of Jesus' life. This is done through the subdivision

of some of the longer sections into smaller, more manageable portions.

For convenience, however, Robertson's paragraph numbers have been retained

and assigned lowercase suffixes, such as a, b, c, to indicate subdivisions.

Also, explanatory footnotes of historical and geographical features, of

theological and chronological relationships, and of a variety of other

matters have been multiplied in this revision. These [p.6] enable

a reader to focus quickly upon major themes in the process of their unfolding.

The Broadus-Robertson proposed divisions of Christ's life have been retained

because of their accuracy. Differences in viewpoint about the placement

of a few sections, however, are reflected in the footnotes of this revision.

In such cases the placement of the text remains the same as is found in

Robertson, with the preferences of the revisers indicated by bracketed

section titles and Scripture references only. Another difference from Robertson

lies in the choice of section titles. In practically all cases a new title

that more accurately portrays the substance of the sections' content has

been assigned.

Perhaps the greatest expansion in our revision lies in the reworking of

Robertson's "Notes on Special Points," found at the end of his Harmony.

Criticism of the gospels and of specific features in them has been the

focal point of New Testament scholarship through the middle six decades

of this century. Discussion generated by this activity has necessitated

a thorough reworking of these, even to the point of isolating new topics

to which the essays (no long "notes") are devoted. A selected reading list

appears at the conclusion of each of these twelve essays, so that those

interested in pursuing the subjects further have suggested resources.

Another marked difference from the earlier works is the Bible translation

employed. In place of the English Revised Version (1881) of Broadus's Harmony

and Robertson's Harmony, the New International Version has been

chosen for this revision. This version is a fresh translation into smoothly

flowing contemporary English that provides insights into the gospels that

have often been veiled from those less familiar with the Old English style

of the Revised Version.

Other aspects of this Harmony are explained in "Explanation of the

Harmony's

Format and Features," and their resemblance to or difference from Robertson

can be observed by those familiar with this time-honored work. Two broad

comparisons are worthy of special note here. First, Broadus's column sequence

for listing the texts has been followed. From left to right, it is Matthew,

Mark, Luke, John. This varies from the order of Robertson, who reversed

Matthew and Mark because he thought Mark wrote first and Matthew depended

on him. After more than a century of popularity, the theory of Marcan priority

is encountering a declining acceptance and, in the opinion of the revisers,

has little to commend it in comparison with the more traditional view of

Matthean priority. Hence the reversion to Broadus's sequence.

The second comparison lies in eschatological perspective. Occasionally

Broadus and Robertson reflected the amillennial or postmillennial temperament

of their times. The twentieth century has witnessed a surge of interest

in the premillenial interpretation of Scripture. It is the [p.7] persuasion

of the revisers that a consistent grammatical-historical interpretation

of the Bible inevitably leads to this latter view. For this reason several

of the explanatory footnotes reflect a corresponding difference in perspective

from the earlier editions.

Besides the text of the Harmony, a number of other features have

been incorporated. An outline of the Harmony, which follows the

probable chronological sequence of Christ's life, follows the Preface.

The same outline is woven into the body of the Harmony. a glance

at this outline reflects when various events occurred in relation to each

other. Whenever possible, the geographical location of each event is given

in the body of the Harmony. The maps at the close of the volume

provide a means of identifying these places in relation to the rest of

Palestine. The sources of Old Testament quotations have also been included,

as have notes clarifying some of the New International Version renderings.

Sections of the Harmony that bear a special resemblance to other

sections have also been noted in the Harmony proper. All section

cross-references are listed in the "Table of Section Cross-References"

found at the back of the volume. This table also notes what the points

of similarity between sections are. The "Table for Finding Passages in

the Harmony" facilitates the locating of any passage in the Harmony

by listing the passages according to chapter and verse sequence. Time lines

for the whole Life of Christ, the Ministry of Christ, and Passion Week

have also been included for the sake of showing broad chronological relationships.

A harmony of the gospels provides an important means for studying the four

gospels at one time. Though it could never completely replace the four

gospels studied individually, it is an indispensable tool for gaining a

well-rounded overview of Jesus' life in all its facts. The editors have

geared this work to provide such an overview for those studying in a college

or seminary. yet a serious student of Scripture studying privately and

without a familiarity with New Testament Greek will be able to follow the

discussion easily. Detailed and technical issues belonging to more advanced

levels of scholarship have not, of course, been included in the work.

In recent years the practice of harmonization has received increasing criticism

in some scholarly circles. Even some who are evangelical have wondered

about its legitimacy. Needless to say, we make no apologies for this Harmony,

because we have confidence in the historical accuracy of the events recorded

in the gospels. If they are historically accurate, they are in principle

harmonizable into a historical sequence that can be read and studied with

profit by followers of Jesus Christ. Christianity is a faith that is solidly

anchored in history. It requires such an exposition of its historical foundation

as is provided by a harmonization of the gospels.

1.3.1.2 Synopsis

As is detailed in some of

the materials below, the gospel synopsis emerged beginning in the early

1900s in a way distinct from the gospel harmony. The major difference was

the basic lack of interest in developing a chronological framework for

studying the life of Christ. Instead, the gospel synopsis became a tool

used largely in more technical studies beginning with Source and Form Criticism.

In the endeavor to discover both the sources used by the gospel writers

and also to attempt a reconstruction of the period of oral transmission

of the Jesus tradition from the middle 30s to the middle 60s of the first

Christian century, this tool became particularly useful in analyzing individual

Greek text pericopes. This was achieved by simply placing the double or

triple tradition Greek texts side by side in parallel columns. This kind

of analysis depended upon a Greek text synopsis, rather than an English

translation based synopsis.

Yet, by the middle of the

twentieth century the gospel synopsis appeared in English translation form,

and began to blur the line of distinction between a synopsis and a harmony.

A broad historical framework surfaces as an organizing structure. Various

approaches then are utilized to handle the specific pericopes. Toward the

end of the twentieth century, scholarly discussion here was focused more

on the Source Critical assumptions that provided the format structure.

Should the synopsis be based on Marcan priority or Matthean priority? Is

it possible to create a format structure without making one of these assumption?

Most scholars today concur that a gospel synopsis must begin with an assumption

regarding the literary relationship of the synoptic gospels. Perhaps, the

only way to avoid this is to produce a three volume synopsis where each

canonical gospel is assumed as the organizing framework. Then, there's

always the issues of the fourth gospel and of the apocryphal gospels, especially

the Gospel of Thomas. How should they be treated?

Other Viewpoints:

Mahlon H. Smith's definition of "Synopsis"

in his A

Synoptic Gospels Primar: Parallel Texts in Matthew, Mark and Luke.

An overview. The term was classically

used in literature to refer to a brief summary or abstract of a work. J.

J. Griesbach's Synopsis of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark & Luke

(1776), however, gave it quite a different technical meaning for biblical

studies. Griesbach printed the complete text of the first three canonical

gospels in columns so scholars could compare parallel passages in each

text at a glance. His work was a synopsis in the root sense of the term

since it let readers "see (everything) together." Thus, a gospel synopsis

is not a summary but, rather, a compendium of related texts.

Griesbach's use of the name was novel but

the format of printing parallel material from different texts on the same

page was not. Origen's Hexapla (3rd c.CE) paralleled 6 versions of the

Jewish scriptures. The Protestant reformer A. Osiander's Gospel Harmony

(1537) adopted the parallel format in printing the 4 canonical Greek gospels.

For more than 2 centuries NT scholars tried to improve Osiander's format,

until Griesbach abandoned the attempt to coordinate John with Matthew,

Mark & Luke. Griesbach chose not to use the traditional term "harmony"

to describe his 3 column work, since that term in music implied blending

4 tones. After Griesbach gospel parallels generally omitted John. So Matthew,

Mark & Luke were called "the synoptics" & study of their relationship

has been designated "the synoptic problem." In 1964, however, K. Aland

revived the 4 gospel synopsis. Yet ,the term "synoptic" is still generally

used to designate only material from Matthew, Mark & Luke, since the

narrative sequence & contents of John are quite independent of the

other gospels.

R. W. Funk's New Gospel Parallels [Sonoma

CA: Polebridge Press, 1990] introduced a further refinement of the traditional

gospel synopsis by printing phrases in parallel gospel passages on the

same line. The matched column synopsis aids analysis by focusing readers'

attention on similarities & differences in each text. This format has

been adapted for this electronic synopsis.

A second distinctive feature of New Gospel

Parallels is its inclusion of non-canonical parallels to gospel passages.

These cannot be ignored in determining the relationship between gospel

texts, since the ms. evidence for some of these (notably, the gospel of

Thomas & the Egerton gospel) is as old or older than any copy of the

synoptic gospels. Here significant non-canonical parallels are presented

after analysis of the synoptic source theories. This location is dictated

by pedagogical logic & the margins of a computer monitor. It does not

infer that the material in these passages was drafted later than Matthew,

Mark & Luke.i

This sample synopsis presents a detailed analysis

of the parallel passages:

Matt 12:46-13:51

Mark 3:31- 4:34

Luke 8:4-21, 13:18-21.

Ernest de Witt Burton and Edgar Johnson Goodspeed,

A

Harmony of the Synoptic Gospels in Greek, (1920), p.vi.

As the purpose of this book is not harmonization or the discovery from

the narrative of a historical order of events, but the exhibit of the facts

respecting the parallelism of the Gospels as they stand, we have in general

retained each of the three Gospels in its own order. The only exceptions

to this statement are that the material of Matt. chaps. 8-11, in which

Matthew has followed an order of his own, we have arranged in the order

of the other evangelists, and that Luke 8:19-21, which though closely parallel

to Mark 3:13-35 is placed by Luke after the Parables by the Sea instead

of before them as in Mark, we have placed in Mark's position.

We have

found the intricate documentary relationships of the Synoptic Gospels greatly

clarified by making a sharp distinction between (1) parallel sections,

and (2) parallel material in non-parallel sections. Parallel sections are

sections which by position and content or by content only are show to be

as sections basically identical -- narratives of the same event, or discourses

dealing with the same subject in closely parallel language. They may differ

greatly in extent by reason of one evangelist's including material which

another omits. Parallel passages in non-parallel sections are passages

which, though standing in sections not basically identical, closely resemble

each other in thought or language. This Harmony places in parallelism

not only the whole of the two or more parallel sections but also all parallel

material in non-parallel sections. The latter is printed in smaller type

and sometimes for practical convenience at the bottom of the page.

Albert Huck and Heinrich Greeven,

Synopsis

of the First Three Gospels, 13th revised ed. (1981), p. v.

When Albert Huck's "Synopsis of the first three Gospels" appeared in 1892

it was expressly intended to serve the hearers and readers of HJ Holtzmann's

lectures on the Synoptic Gospels as a textbook. This association with a

particular theory was, however, gar too close and was soon (3rd edition,

1906) given up, so that Huck could in due course of time become the tool

that it still is today, a clear and full presentation of the facts which

give rise to the Synoptic problem and which must be explained by any solution

of it. Theories formerly widely accepted are being questioned anew and

as this book was long ago so it is today concerned to maintain a strict

neutrality before the various suggested solutions of the Synoptic problem.

For the few instances in which it appears otherwise (simply because each

possible kind of arrangement seems to favour a particular theory) I expressly

declare that no such attempt to preempt the solution is intended. Even

the arrangement of the columns (Mt, Mk, Lk) merely follows the order of

the Gospels which is customary today.

1.3.2

Types of Gospel Synopses

From the above discussion,

you can readily conclude that the varying assumptions are going to produce

a variety of gospel harmonies and synopses. Each one will work off its

own adopted set of assumptions and these will produce variations in the

final product, especially in formatting. Below we will explore two areas:

(1) variations in format; (2) Presuppositions in Critical Methodology.

1.3.2.1 Format Variations

In general, the foundational

variation will surface on whether to line up the parallel scripture texts

either vertically or horizontally. In either instance the goal is to facilitate

more precise analysis of the double and triple tradition materials. The

comparing of the same event by two or more of the gospel writers enables

the student to see both similarities and differences among the writers.

How this analysis is used will depend upon the goal for such study.

1.3.2.1.1 Vertical Column Synopses

By far the most common format

for both the harmony and the synopsis has been the vertical parallel column

structure. The following example somewhat recreates this format, but with

limitations because of the limits with html formatting for the internet.

| Mt. 12:46-50 (NRSV) |

Mk. 3:31-35 (NRSV) |

Lk. 8:19-21 (NRSV) |

| (S1) 46 While he

was still speaking to the crowds, his mother and his brothers were standing

outside, wanting to speak to him. |

| (S2) 47 Someone

told him, "Look, your mother and your brothers are standing outside, wanting

to speak to you." |

| (S3) 48 But to the

one who had told him this, Jesus replied, "Who is my mother, and who are

my brothers?" 49 And pointing to his disciples, he said, "Here are my mother

and my brothers! 50 For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is

my brother and sister and mother." |

|

| (S1) 1 Then his

mother and his brothers came; and standing outside, they sent to him and

called him. |

| (S2) 32 A crowd

was sitting around him; and they said to him, "Your mother and your brothers

and sisters are outside, asking for you." |

| (S3) 33 And he replied,

"Who are my mother and my brothers?" 34 And looking at those who sat around

him, he said, "Here are my mother and my brothers! 35 Whoever does the

will of God is my brother and sister and mother." |

|

| (S1) 19 Then his

mother and his brothers came to him, but they could not reach him because

of the crowd. |

| (S2) 20 And he was

told, "Your mother and your brothers are standing outside, wanting to see

you." |

| (S3) 21 But he said

to them, "My mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God

and do it." |

|

In this system the parallel texts are laid out side-by-side for comparison.

Additionally, in printed copies (not possible to reduplicate in html electronic

format) sentences often are broken up into words and phrases which are

then set up on the same lines horizontally across the page in order to

more quickly notice the exact parallels of smaller units of material. A

few of the synopses will also contain the Greek text on the left page and

an English translation text on the opposite right page. This allows the

Bible student to check both the Greek and the translation texts for parallels.

A major example of this type is Aland, Kurt. Synopsis of the Four Gospels

Completely Revised on the Basis of the Greek Text of the Nestle-Aland 26th

Edition and Greek New Testament 3rd Edition : The Text is the Second Edition

of the Revised Standard Version.

1.3.2.1.2 Horizontal Line Synopses

Several years ago an alternative

format was introduced, which has had limited success; this layout places

the parallel texts in horizontal columns stacked on top of one another.

The most ambitious effort at this is the multi-volume work of Reuben J.

Swanson with his The Horizontal Line Synopsis of the Gospels (Greek

Edition). Volume 1, The Gospel of Matthew. [Dillsboro, NC: Western

North Carolina Press, Inc., 1982.]. His approach follows the older vertical

column pattern with the breaking up of sentences into smaller syntactical

units with appropriate spacing to enable a visually quickly identification

of the parallel units. He began this work with an English translation text

version in 1975. The stated purpose of this alternative format was to achieve

a more neutral Source Critical format (see topic 1.3.2.2.2 below for details).

One of the formatting issues with the vertical column synopsis is the adoption

of Matthean or Markan priority Source Critical assumptions as foundational

to the sequencing of the materials. Whether or not the horizontal line

synopsis successfully achieves this neutrality is very debatable, but at

least the intent is important to note.

Mt.

(NRSV) |

(S1) 46

While he was still speaking to the crowds, his mother and his brothers

were standing outside, wanting to speak to him.

(S2) 47 Someone told him,

"Look, your mother and your brothers are standing outside, wanting to speak

to you."

(S3) 48 But to the one who

had told him this, Jesus replied, "Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?"

49 And pointing to his disciples, he said, "Here are my mother and my brothers!

50 For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister

and mother." |

Mk.

(NRSV) |

(S1) 1 Then his mother

and his brothers came; and standing outside, they sent to him and called

him.

(S2) 32 A crowd was sitting

around him; and they said to him, "Your mother and your brothers and sisters

are outside, asking for you."

(S3) 33 And he replied,

"Who are my mother and my brothers?" 34 And looking at those who sat around

him, he said, "Here are my mother and my brothers! 35 Whoever does the

will of God is my brother and sister and mother." |

Lk.

(NRSV) |

(S1) 19 Then his mother

and his brothers came to him, but they could not reach him because of the

crowd.

(S2) 20 And he was told,

"Your mother and your brothers are standing outside, wanting to see you."

(S3) 21 But he said to them,

"My mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and do it." |

1.3.2.2 Critical Presuppositions

Before one begins to create

a gospel synopsis several crucial assumptions about the three gospels and

the study of the life of Jesus must be made, since these will largely shape

the format of the synopsis. Three of the more important assumptions are

explored below.

1.3.2.2.1 Historical Critical Assumptions

Whether one attempts to

produce a gospel harmony or a gospel synopsis -- or a mixture of the two

-- is largely determined by one's views of the historical Jesus. This gets

us into the infamous Quest

for the Historical Jesus debate (for a more detailed discussion see

my outline and links in the Issue of the

Historical Jesus discussion). Two extremes of viewpoint typically surface.

The older, uncritical, and sometimes naive view that the gospels are basically

historical documents telling the story of Jesus much as a modern biographer

would have. The assumption of modern standards of objectivity in recounting

the past plays a substantial role. This leads to the gospel harmony approach

with the contention that it is the only legitimate way to set up the scripture

texts telling the story of Jesus.

The other extreme is the

deep skepticism over whether or not a historical person named Jesus of

Nazareth ever lived or not. The rigid application of emerging definitions

of history and standards of evaluating sources that characterized the early

years of the developing Historical Critical Methodology in the 1700s produced

high levels of skepticism regarding how much reliable data could be gleaned

from the canonical gospels in order to write a biography of the life of

Jesus. This led to the rejection of the gospel harmony approach in favor

of the gospel synopsis approach as a study tool for the life of Jesus in

the gospels. One of the more intriguing examples of this is the work of

the early American president Thomas Jefferson [Jefferson, Thomas, Richard

Francis Weymouth, and Henry E. Jackson. The Thomas Jefferson Bible Undiscovered

Teachings of Jesus. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1923.]. Jefferson's

English Deism religious views led him to totally reject all aspects of

the supernatural in the gospel accounts as having any historical credibility.

Thus his 'harmony' of the life of Jesus only included the teaching and

actions of Jesus that gave no hint of the supernatural.

The viewpoint taken here

stresses the basic historical reliability of the content of the synoptic

gospels, but at the same time seeks to take into full account the severe

limits of the gospel materials for reconstructing a full account of Jesus

life and ministry. The limits of the canonical gospels in providing historical

data prevent any successful biography of Jesus from being written while

using modern standards of biographical writing. The modern Criteria for

Authenticity employed in the current Quest

for the Historical Jesus by the so-called Jesus'

Seminar represent a severely skeptical set of assumptions far too heavily

dependent upon the old, outmoded empirical views of history. These flow

out of the modern western 'Scientific Methodology' which begins with doubt

and questioning of the trustworthiness of everything. This negative starting

assumption flies in the face of the character and integrity of the gospel

writers whose spiritual experience with the resurrected Jesus provided

them with a concern to tell the story of Jesus with truthfulness and honesty.

To me, questioning and skepticism only become legitimate when the available

data legitimately raises uncertainty about what may have actually happened

during the earthly life of Jesus. To be sure, such instances do arise when

studying the canonical gospels. But this is a very different stance than

beginning with the assumption that nothing written in the canonical gospels

can be trusted at all. The gospels, indeed, aren't biographies of Jesus.

Instead, as Redactional Critical studies have clearly demonstrated, they

were written as 'propaganda' pieces. That is, each gospel writer had a

theological perspective about the religious, spiritual significance of

Jesus of Nazareth and was fore mostly concerned to communicate that understanding

with his initial readership as a means of encouraging faith in and commitment

to Jesus as the divinely sent Savior of the world. But this doesn't mean

that reliable historical content didn't serve as the building block sources

for their telling the story of Jesus.

Thus we will approach the

study of the life of Jesus with a basic confidence in the reliability of

the information in the canonical gospels. But we will not be willing to

duck hard questions nor sweep difficult historical issues under the carpet

so as to pretend they don't exist.

1.3.2.2.2 Source Critical Assumptions

This has to do with the

'literary' relationship among the synoptic gospels. Although many varieties

of viewpoint exist today, the two more commonly viewpoints are the Holtzmann

Marcan Priority view, usually labeled the Two Source Hypothesis, and the

Griesbach Matthean Priority view, usually labeled in its current expression

as the Two Gospel Hypothesis. These two we will give some attention to

in this study.

Two

Source Hypothesis.  This view works off the assumption that Mark was the first canonical gospel

to be written and that Matthew and Luke additionally made use of a second

source termed Q (for the German word Quelle meaning source). You should

read the details of this both in the web site Synoptic Theories &

Hypotheses at http://www.mindspring.com/~scarlson/synopt/

and especially in W.G. Kümmel's Introduction to the New Testament

(Section 5, "The Synoptic Problem," in Part I.A. in the Cokesbury iPreach

Bible Reference materials under Biblical Reference). Prof. Kümmel

has a detailed, extremely important explanation and defense of the Marcan

priority view.

This view works off the assumption that Mark was the first canonical gospel

to be written and that Matthew and Luke additionally made use of a second

source termed Q (for the German word Quelle meaning source). You should

read the details of this both in the web site Synoptic Theories &

Hypotheses at http://www.mindspring.com/~scarlson/synopt/

and especially in W.G. Kümmel's Introduction to the New Testament

(Section 5, "The Synoptic Problem," in Part I.A. in the Cokesbury iPreach

Bible Reference materials under Biblical Reference). Prof. Kümmel

has a detailed, extremely important explanation and defense of the Marcan

priority view.

In this approach the assumption

is that Mark wrote his gospel story first. Later Matthew and Luke, working

independently of each other, had access to copies of Mark's gospel and

a collection, largely of Sayings materials, as a second source. From these

two sources, and also from others sources that each had exclusive access

to (the M and the L sources in Streeter's Four Source Theory), these subsequent

gospel documents were composed.

Two

Gospel Hypothesis.  This

view has two segments to its existence among NT scholars. The older view

reaches back to Johann Jakob Griesbach who first proposed a detailed defense

of it in 1783. Griesbach's view did not gain substantial influence because

of the dominance of the Marcan priority view which controlled gospel scholarship

for most all the 1800s and 1900s. Then in the middle of the 1900s

Professor Bill Farmer began a crusade to revise the old Griesbach view

with substantial revisions and updating. Over the past fifty years this

alternative view has found substantial support in the work of NT scholarship

on both sides of the Atlantic, so that it now represents a serious alternative

view to the Marcan priority perspective.

This

view has two segments to its existence among NT scholars. The older view

reaches back to Johann Jakob Griesbach who first proposed a detailed defense

of it in 1783. Griesbach's view did not gain substantial influence because

of the dominance of the Marcan priority view which controlled gospel scholarship

for most all the 1800s and 1900s. Then in the middle of the 1900s

Professor Bill Farmer began a crusade to revise the old Griesbach view

with substantial revisions and updating. Over the past fifty years this

alternative view has found substantial support in the work of NT scholarship

on both sides of the Atlantic, so that it now represents a serious alternative

view to the Marcan priority perspective.

In this perspective, Matthew

was the first to compose his gospel, then Luke wrote his utilizing material

from Matthew (thus eliminating the need for the Q document hypothesis in

the Two Source view). Finally, Mark used both Matthew and Luke to compose

his much shorter gospel story of Jesus.

Bibliography:

Synoptic Theories &

Hypotheses at http://www.mindspring.com/~scarlson/synopt/

An extremely helpful web site that explains in simple terms the fundamental

issues involved here.

W.G. Kümmel's Introduction

to the New Testament (Section 5, "The Synoptic Problem," in Part I.A.

in the Cokesbury iPreach

Bible Reference materials under Biblical Reference).

This is a most important source for understanding the details of the issue

of the Synoptic Problem!

"Synoptic Problem,"

Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible (in volume 4 in the Cokesbury

iPreach

Bible Reference materials under Dictionaries, Handbooks,

and One Volume Commentaries).

1.3.2.2.3 Form Critical Assumptions

Form Criticism, first labeled

in its German origin Formgeschichte (history of forms), builds on the Source

Critical conclusions, but takes its concerns forward (history of mid-first

century Christianity) instead of backward (reaching back to the uses of

existing written sources) as does Source Criticism. Its work is in two

specific areas: (1) the identification of established literary patterns

of written expression (genres) in the synoptic gospel material, and (2)

how those forms communicated Christian teaching in early Christianity beginning

in the second half of the first Christian century.

Thus, comparative study

of ancient Jewish and Greco-Roman literature to develop a background understanding

of existing genres of written materials was foundational to this approach.

This was then applied to the contents of the synoptic gospels to see both

similarities and differences. The similarities identified connecting links

of early Christianity to both Jewish and Greco-Roman religious/philosophical

thinking in the ancient world. The differences highlighted the creativity

of the early Christianity community to develop new, fresh modes of expression

in order to better communicate its understanding of the Gospel message.

Once these genres at many different levels of writing had been identified

in the synoptic gospels, the challenge was to probe how these patterns

of expression were used in the early church to address issues about the

nature and function of the Christian religion. This is perhaps the least

successful and lasting part of the older Form Critical methodology. One

positive contribution was the refocusing of attention on the book of Acts

in the NT and its close connection to the canonical gospels.

Bibliography:

"Form Criticism," Interpreter's

Dictionary of the Bible (in volume 2 in the Cokesbury iPreach

Bible Reference materials under Dictionaries, Handbooks,

and One Volume Commentaries).

1.3.3

How to Use a Gospel Synopsis

Methodology for Color Coding:

Mark Goodacre's suggestions

are quite helpful and will be followed here; see the page, The

Synoptic Problem: a Way through the Maze. His scheme of color coding

the synoptic gospel texts is simple:

Matthew: blue

Mark: red

Luke: yellow

Matthew + Mark: purple [ i.e. blue

+ red ]

Matthew + Luke: green [i.e. blue + yellow

]

Mark + Luke: orange [ i.e. red + yellow ]

Matthew + Mark + Luke: brown [ i.e. blue +

red + yellow ]

The procedure is rather simple to follow. Dr. Goodacre has samples posted

on the above web site to illustrate what is involved in the process. This

should be done electronically, if possible, using a computer word processing

software (e.g., MS Word, Corel Word Perfect) or web authoring software

(Netscape Composer, Adobe GoLive). The colors can be identified in the

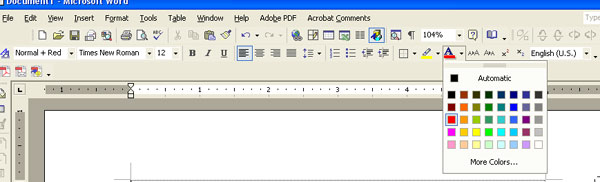

Text Color icon in most software. See the below example from MS Word XP:

The above coding system needs to be followed exactly in order for the conclusions

(see below) to be accurate. Let's use the above pericope as our working

text. I've inserted the Greek text for each gospel pericope along side

the NRSV translation. This enables one to see more clearly the precise

differences that may not be readily apparent in an English translation.

The use of bold face font style helps to bring out the color coding better.

The above coding system needs to be followed exactly in order for the conclusions

(see below) to be accurate. Let's use the above pericope as our working

text. I've inserted the Greek text for each gospel pericope along side

the NRSV translation. This enables one to see more clearly the precise

differences that may not be readily apparent in an English translation.

The use of bold face font style helps to bring out the color coding better.

| Mt. 12:46-50 (NRSV) |

Mk. 3:31-35 (NRSV) |

Lk. 8:19-21 (NRSV) |

| (S1) 46 While

he was still speaking to the crowds, his mother

and his brothers were standing

outside, wanting to speak to him. |

46

~Eti aujtou' lalou'nto" toi'" o[cloi" ijdou; hJ

mhvthr kai; oiJ ajdelfoi; aujtou' eiJsthvkeisan

e[xw zhtou'nte" aujtw'/ lalh'sai. |

| (S2) 47 Someone

told him, "Look,

your mother and your brothers are

standing outside, wanting

to speak to you." |

[47 ei\pen dev ti" aujtw'/,

jIdou; hJ mhvthr sou kai; oiJ ajdelfoiv sou

e[xw eJsthvkasin zhtou'ntev"

soi lalh'sai.] |

| (S3) 48 But

to

the one who had told him this, Jesus replied,

"Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?"

49 And pointing to

his disciples, he said, "Here

are my mother and my brothers! 50

For whoever does the will of my

Father in heaven

is my brother and sister

and mother." |

48 oJ de;

ajpokriqei;"

ei\pen tw'/ levgonti aujtw'/,

Tiv" ejstin hJ mhvthr mou kai; tivne" eijsi;n oiJ ajdelfoiv mou;

49

kai; ejkteivna"

th;n cei'ra aujtou' ejpi; tou;" maqhta;" aujtou' ei\pen,

jIdou; hJ mhvthr mou kai; oiJ ajdelfoiv mou.

50 o^sti"

ga;r a]n poihvsh/ to; qevlhmatou' patrov"

mou tou' ejn oujranoi'" aujtov" mou

ajdelfo;" kai; ajdelfh; kai;

mhvthr ejstivn. |

|

| (S1) 31 Then his

mother and his brothers came; and

standing outside, they

sent to him and called him. |

31 Kai; e[rcetaihJ

mhvthr aujtou' kai; oiJ ajdelfoi; aujtou' kai;

e[xw sthvkonte" ajpevsteilan

pro;" aujto;n kalou'nte" aujtovn. |

| (S2) 32 A

crowd was sitting around him; and they said to

him,

"Your mother and your brothers

and sisters are outside,

asking for you." |

32 kai; ejkavqhto peri;

aujto;n o[clo", kai; levgousin aujtw'/,

jIdou; hJ mhvthr sou kai; oiJ ajdelfoiv sou

[kai;

aiJ ajdelfai sou] e[xw

zhtou'sivn se. |

| (S3) 33 And

he replied, "Who

are my mother and my brothers?" 34 And

looking at those who sat around him, he

said, "Here are my

mother and my brothers! 35 Whoever

does the will of God

is my brother

and sister and mother." |

33 kai; ajpokriqei;"

aujtoi'" levgei,

Tiv"

ejstin hJ mhvthr mou kai; oiJ ajdelfoiv [mou];4

kai; peribleyavmeno"

tou;" peri; aujto;n kuvklw/ kaqhmevnou" levgei,

#Ide hJ mhvthr mou kai; oiJ ajdelfoiv mou.

35

o^" [ga;r]

a]n poihvsh/ to; qevlhma tou'

qeou', ou|to"

ajdelfov" mou kai;

ajdelfh; kai; mhvthr ejstivn. |

|

| (S1) 19 Then

his mother and his brothers came

to him, but

they could not reach him because of the crowd. |

19 Paregevneto de; pro;"

aujto;n hJ mhvthr kai; oiJ ajdelfoi; aujtou'

kai; oujk hjduvnanto suntucei'n aujtw'/ dia;

to;n o[clon. |

| (S2) 20 And

he was told, "Your mother and your

brothers are

standing outside,

wanting to see you." |

20 ajphggevlh de; aujtw/'/,

JH mhvthr sou kai; oiJ ajdelfoiv sou eJsthvkasin

e[xw ijdei'n

qevlontev"

se. |

| (S3) 21 But

he

said to them, "My

mother and my brothers are those who hear

the word of God

and do it." |

21 oJ de;

ajpokriqei;"

ei\pen pro;" aujtouv",

Mhvthr mou kai; ajdelfoiv mou

ou|toiv eijsin oiJ to;n lovgon tou'

qeou'

ajkouvonte" kai; poiou'nte". |

|

Although this takes some time and careful study, once it is completed

the similarities and differences among the synoptic gospel writers becomes

very clear. The next step in the process is to tabulate the similarities

and differences in a chart listing.

Tabulation of Color Coding Results:

Agreements

of all

three synoptic

gospel writers: |

Agreements

of

Matthew

and

Mark: |

Agreements

of

Matthew

and

Luke: |

Agreements

of

Mark

and

Luke: |

Uniquely

Matthean: |

Uniquely

Marcan: |

Uniquely

Lucan: |

| Scene 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. his mother and

his brothers |

1. standing outside |

|

|

1. While he was

still speaking to the crowds,

2. were

3. wanting

to speak to him. |

1. came

2. and

3. they

sent to him and called him. |

1. Then

2. came

to him

3. but they could

not reach him because of the crowd. |

| Scene 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. him

2. your mother and

your brothers

3. outside

4. you |

1. Look |

1. are standing |

|

1. Someone told

2. wanting to speak

to |

1. A crowd was sitting

around him

2. and

sisters are

3. asking

for |

1. And he was told

2. wanting

to see

|

| Scene 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. said

2. my mother and

my brothers |

1. replied

2. "Who is my mother,

and who are my brothers?"

3. And

4. Here

are

5. For

whoever does the will of

6. is

my brother and sister and mother. |

1. But

|

1. of God

|

1. to the one who

had told him this

2. pointing to his

disciples

3. my Father in

heaven |

1. And

2. looking at those

who sat around him

|

1. are those who

hear the word

2. and do it. |

Interpreting the Results of your Analysis:

1. With Source Critical Concerns:

In very technical objectives

the NT scholar would carefully examine the words, phrases, etc. of the

Greek text for signals suggesting whether Mark was the written source for

Matthew and Mark (Two Source Hypothesis), or whether Matthew was the source

for first Luke, and then whether Mark made use of both Matthew and Luke

(Two Gospel Hypothesis).

Once a conclusion is reached

in this regard, then each pericope is exegeted against this background

of literary dependency.

2. With Form Critical Concerns:

Form Criticism, especially

in its earlier expressions, typically assumed the Two Source hypothesis

mentioned above, and once it had isolated out the pericope units for each

gospel document, then focused on an attempted explanation of how the distinctives

of each pericope were developed by each gospel writer to address similar

but distinctively different situations in the initial targeted readers,

or communities -- as they then to be labeled -- that the gospel writer

was addressing. The concern is to understand as much as possible about

both the oral transmission period (30s to 60s) and the developed communities

(60s to 80s) at the time of the writing of each document. This created

three settings for analyzing the gospel texts: the Sitz im Leben Jesu

(the setting of the historical Jesus, where authentic says of Jesus

were presupposed); the Sitz im Leben Kirche (the setting of the

early church from the 30s to the 60s); and the Sitz im Leben Verfassers

(the setting of the gospel writer and his targeted community in the 60s

to the 80s). The work of Dibelius and Bultmann who were early pioneers

in Form Critical studies (in German it is called Formgeschichte

[history of forms]) made significant contributions to the study of both

the life of Jesus and early Christianity. For Rudolf Bultmann, the older

(first) quest for the historical Jesus had run into a dead end by the end

of the 1800s and left honest scholarship with no conclusion but that no

real proof that Jesus of Nazareth ever lived. His way around this in order

to salvage a meaningful religious faith was to suggest that the vast majority

of the gospel material was a interpretative creation of apostolic Christianity

in an effort to find relevance of the resurrected, spiritual Christ to

issues and situations being faced by various Christian communities from

the late 30s onward. That is the period of time largely described in the

Book of Acts in the NT. Thus in this approach the gospels supplement the

story of early Christianity contained in Acts, much more than they inform

us about Jesus of Nazareth. Therefore the focus of exegesis is upon the

Sitz im Leben (Kirche and especially Verfasser). But many severe limitations

on this methodology began surfacing very quickly starting in the early

1900s. Most of Bultmann's assumptions about the historical Jesus have been

profoundly revised or discarded. The obvious compositional intention of

each gospel to tell the story of Jesus of Nazareth, rather than that of

the Christ of faith, to their individual audiences has been reaffirmed,

rather than rejected as Bultmann largely did.

Yet, elements of this approach

remain important and vital to insightful exegesis of the gospel texts.

This will become clearer as we proceed further.

Additionally, the later

Redactional Critical methodology utilized the literary analysis aspects

of Form Criticism especially as a part of its probing of the gospel documents

in order to distill out the theology, or the religious perspective, of

each gospel writer. Its holistic concerns to see the 'big picture' theologically

of each gospel has served as a helpful corrective to some of the deficiencies

of the Form Critical approaches. The Sitz im Leben (Verfassers)

concern of Form Criticism remains a major concern of Redactional Critics,

only with a theological distinctive twist.

3. With Exegetical Concerns:

When the Bible student begins

to interpret the Jesus tradition seriously with detailed analysis, some

preliminary decisions will have to be made in order to provide starting

points for a detailed exegesis of the gospel passages in parallel with

one another. The issue of the perceived literary connection among the synoptic

gospels will need a decision. Although impressed by the Two Gospel Hypothesis

myself, I gravitate toward the older, more widely established Two Source

view that understands Mark being the first written gospel, then followed

by Matthew and then Luke who worked with a source common to them, the so-called

Q source. Additionally, the interest in the later setting of mid-first

century Christianity that grew out of the Form Critical and later Redactional

Critical concerns is legitimate. The initial readership of these gospel

documents were the different Christian communities who represented a second

generation of Christians, most of whom had never seen Jesus in person.

They were largely from a dramatically different ethnic and linguistic background.

Thus, the issue of the relevance of what Jesus said and did while on earth

to their spiritual needs and interests is vitally important. In my estimation,

the canonical gospels were written to address this very concern. Therefore,

whatever can be gleaned about these early Christian communities helps us

see more clearly how each gospel writer interpreted the significance of

Jesus to his targeted audience.

Now for some more pragmatic

concerns. How does one make sense out of the above tabulation of similarities

and differences with some of these starting assumptions discussed in the

two topics above? Several observations come to the surface.

1. Luke places less emphasis

on this episode than do Matthew and Mark. His narrative is much shorter

and generic in its descriptive details. The question then arises: was Luke

less interested in the relationship that the adult Jesus had with his fleshly

family? If so, then why? The answer to that question lies in tracing out

other Lucan pericopes that possibly touch on Jesus' family.

2. While true kinship with

Jesus is based on knowing and doing the Father's will in Matthew and Mark,

in Luke it is based on hearing and doing the word of God. All three see

Jesus addressing the issue of spiritual kinship, but Luke defines that

on the basis of the orally preached Gospel message. Matthew and Mark see

it defined on a broader basis of the will of God. Is there something in

the Lucan community that needs addressing in regard to the importance of

the preached Gospel message? Perhaps so. A concordance tracing of the phrase

'word of God' in Luke reveals the use of this phrase four times (5:1; 8:11;

8:21; 11:28), over against one each in Matthew (15:6) and in Mark (7:13).

In Matthew and Mark this phrase is another way of saying 'Old Testament'

while in Luke it is synonymous with 'Gospel' in oral proclamation. Obeying

this Gospel proclamation is a significant issue for Luke also in his use

of the expression.

3. Somewhat surprisingly

Matthew and Mark include a fuller set of family terms -- mother, brothers

and sisters -- while Luke only refers to 'mother and brothers.' Luke typically

includes social groups that first century Jewish patriarchal tradition

would not emphasize, but here Mark and Matthew do this. Assuming Matthew

is using Mark here -- the expressions are identical both in the NRSV translation

as well as the underlying Greek text -- then Mark is perhaps implying that

Jesus' sisters shared in the apprehension over what Jesus was doing along

with his mother and brothers. A concordance search of the word 'sister*'

reveals a common pattern in both Mark (5x) and Matthew (7x) of 'brother

and sister,' while Luke (1x) seldom makes use of the phrase 'brother and

sister.' This pericope is consistent with the larger synoptic gospel patterns

at this point.

4. Luke tones down the hostility

in Jesus' family when they sought to talk to him by giving a reason why

they waited outside the house and insisted on Jesus coming out to them:

but they could not reach

him because of the crowd. Matthew

and Mark present the episode in more confrontational tones, thus highlighting

the early disenchantment of Jesus' own family members with his developing

ministry. This disenchantment is additionally stressed in Matthew and Mark

by the way Jesus responded to being informed that they wanted to talk to

him. These two gospels add "Who is my mother,

and who are my brothers?" This is in contrast to Luke who glosses

over this part with a much milder: "My mother

and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and do it." The

Marcan gospel has stressed various sources of opposition to Jesus, and

includes his family in that. Matthew picked up on this Marcan emphasis,

but Luke toned it down considerably.

5.

Matthew uses his typical Jewish way of referring to God by the expression

my Father in heaven, while Mark

and Luke, writing to largely Gentiles audiences, use the more direct term

God.

These

are some of the possible implications of such comparative study. Others

can be gleaned for more detailed analysis. You should pay close attention

to commentaries that emphasize the above interpretative strategies in order

to glean additional insights than those you discover through personal study.

One excellent example of this type of commentary is the individual volume

commentary on Matthew by Robert Gundry (Matthew: A Commentary on His

Literary and Theological Art [Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

Company, 1982]). Below is an excerpt from pages 248-250 on Matt. 12:46-50:

In

this section Matthew goes back to Markan material that follows the sayings

on blasphemy of the Spirit and precedes, as here, the parable of the sower.

Luke's parallel appears in a context quite different from both Matthew's

and Mark's contexts. This material takes the place of Luke's similar material

concerning the blessedness of those who hear and observe the word of God

(Luke 11:27-28, omitted by Matthew). By choosing this rather than that

and by introducing it now rather than earlier (i.e., closely after the

sayings about blasphemy of the Spirit [vv 31-32], as in Mark), Matthew

enables himself to finish chaps. 11-12 with a contrast between Jesus' true

relatives and those who persecute Jesus and his disciples. In addition,

Matthew can now move into his next major section, chap. 13, without breaking

stride. He will simply continue with Mark.

12:46 (Mark 3:31-32; Luke 8:19-20) The genitive absolute construction

behind "While he was still speaking to the crowds" characterizes Matthew's

style. "While he was yet speaking" comes from Mark 5:35 (cf. Luke 8:49)

and compensates for Matthew's omitting these words (and much else, too)

between 9:22 and 23. The crowds comes from Mark 3:32. But there a crowd

sits around Jesus and speaks to him; here Jesus is speaking to the crowds.

His topic is the evil generation of scribes and Pharisees (vv 38-54). As

often, Matthew puts the crowds in the plural (despite their being inside

a house!). The reason is probably that they represent the many from all

nations who will become disciples (28:19). This entire genitive absolute

will reappear as an insertion in 17:5 (see also 26:47; Mark 14:43; Luke

22:47).

Jesus' mother and brothers stand outside (i.e., outside the house; see

13:1). Typically, Matthew inserts ijdouv

(34,9). This parallels the ijdouv

with which someone announces their presence to Jesus (v 47; Mark 3:32)

and the distinctive ijdouv

with which Jesus identifies his true relatives (v 49). Matthew conforms

vv 46 and 47 to each other in further respects, too. In v 46 he omits Mark's

"comes," turns Mark's participle "standing" into the finite verb "stood"

(jeiJsthvkeisan;

see 13:2 for another distinctive pluperfect of this verb), substitutes

"seeking" for Mark's "they sent to him" in order to gain a parallel with

"seeking" in v 47, and replaces Mark's "calling him" with "to speak to

him" for correspondence with "speaking to the crowds" in his immediately

preceding genitive absolute. Mark's "An a crowd was sitting around him"

drops out because matthew has already referred to crowds in the genitive

absolute and inserted "around him" in 8:18 (cf. the comments ad loc.).

We now see that advancing the crowds not only provided Matthew with a transition;

it also enabled him to juxtapose Jesus' mother and brothers alongside them.

The reference in 1:25 to Joseph's not having sexual intercourse with Mary

till Mary had given birth to Jesus makes it natural to think of Jesus'

brothers as younger half-brothers. For a lengthy discussion of various

possibilities, see J. B. Lightfoot, The Epistle of St. Paul to the Galatians

(reprinted, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1957) 252-91.

Hopefully from this you can begin

to sense the importance of doing the comparative studies of parallel pericopes

in the Jesus tradition. And also, the helpfulness of the gospel synopsis

as a tool for doing this study. The application of the color coding methodology

will significantly contribute to skill development in spotting the similarities

and differences in these gospel parallels.

This work should be done

on every one of the Exegesis

Assignments that involve double or triple tradition texts! The setting

up of the parallels is done and these html files are hyperlinked

to the pericope title in the list of Presentation

Assignments.

Bibliography

For an online bibliography of resources for the study of the

synoptic gospels see Torrey Seland's page, "Articles etc related to the

Synoptic Gospels," at http://www.torreys.org/bible/biblia02.html#synoptic.

Online Gospel Synopses:

Online Pages for Gospel Synopsis study:

Hardcopy Sources:

For a detailed listing of print volumes see New

Testament Bibliography: Gospel

Synopses and Harmonies in the Bibliography

series at Cranfordville.com.

Dungan, David. "Theory of Synopsis Construction," Biblica 61

(1980), 305-329.

Greeven, Heinrich. "The Gospel Synopsis from 1776 to the present day,"

J.J.