Medieval Interpretation

--Lecture

Notes for Topic 2.1.3-

--Lecture

Notes for Topic 2.1.3- Religion 492

Religion 492

Last revised: 2/23/04

Explanation:

Contained below

is a manuscript summarizing the class lecture(s) covering the above specified

range of topics from the List of Topics for Religion 492. Quite often

hyperlinks (underlined)

to sources of information etc. will be inserted in the text of the lecture.

Test questions for all quizzes and exams will be derived in their entirety

or in part from these lectures; see Exams

in the course syllabus for details. To display the Greek text contained

in this page download and install the free BSTGreek

from Bible Study Tools.

Created

by  a division of

a division of  All rights reserved©

All rights reserved©

|

Go directly

to topic:

2.1.3

Medieval Interpretation |

2.1.3.1

Before 800

Transition from Ancient World |

2.1.3.2

From 800 to about 1150

Early Middle Ages |

2.1.3.3

From about 1150 to 1350

High Middle Ages |

2.1.3.4

From about 1350 to about 1500

Late Middle Ages |

2.1.3.5

Summation |

Bibliography |

|

|

2.1.3

Assigned Readings for This Topic:

Gerald Bray, "Medieval Interpretation," Biblical Interpretation:

Past and Present, pp. 129-164

In trying to understand the development of interpretive methodology during

this period, one has to understand the culture and the currents of historical

ebb and flow. In this Prof. Bray does an excellent job in summarizing the

high points in his first section, "The Period," pp. 129-133. This material

should be studied very carefully, since it provides a critical backdrop

to our focus on the history of interpretation.

A very helpful web site covering life in the middle ages is http://www.learner.org/exhibits/middleages/.

Subpages cover Feudal Life, Religion, Homes, Clothing, Health, Arts, Town

Life and Related Resources. Another helpful background web site is "The

Middle Ages" at http://themiddleages.tripod.com/.

A Google

search generated an index of sub topics related to the study of the

Middle Ages that provides more specific direction on individual topics.

Your introduction to this period of western history should begin with an

exploration of some of these web sites in order to have a backdrop for

understanding the impact of religion, and more precisely how the Bible

was interpreted during this period.

2.1.3.1

Before 800, period transition from the ancient world

Assigned Readings for This Topic:

Gerald Bray, Biblical Interpretation: Past and Present, relevant

sections in this chapter.

Resource Materials to also be studied:

Prof. Bray's characterization of this

period, pp. 131-132:

This was one of

transition from the ancient world, in which most people did not accept

the permanence of the changes which had taken place since the fifth century.

In theory, the Roman Empire continued to exist, with an Emperor at Constantinople,

who would one day reclaim all the territories over which his forebearers

had ruled. This seems like a fantastic dream to us, but it is what most

people at the time believed, and it deeply affected their outlook. Intellectual

life during this period remained vigorous in the East, thought increasing

theological controversy led to a virtual ban on new biblical interpretation

(at the Council in Trullo, 692). Scholarship also enjoyed a remarkable

flowering in the British Isles, where Irish and, later, Anglo-Saxon monks

carried on the traditions of antiquity. Elsewhere, however, this period

was known as the 'Dark Ages' because of the generally low standard of learning.

In trying then to understand developments in the field of biblical interpretation,

the following individuals should be studied, in Prof. Bray's perspective

(pp. 133-135): John Cassian

(360-435); Junilius (fl. c. 550); Isidore of Seville (d. 636); Maximus

the Confessor (580-662); Ambrose Autpert (d. 781); Beatus of Liébana

(c. 750-c. 798); Aldhelm of Mahnesbury (c. 640-709); and Bede (672-735).

John

Cassian:

A monk and ascetic writer of Southern Gaul, and the first to introduce

the rules of Eastern monasticism into the West, b. probably in Provence

about 360; d. about 435, probably near Marseilles. Gennadius refers to

him as a Scythian by birth (natione Scytha), but this is regarded as an

erroneous statement based on the fact that Cassian passed several years

of his life in the desert of Scete (heremus Scitii) in Egypt. The son of

wealthy parents, he received a good education, and while yet a youth visited

the holy places in Palestine, accompanied by a friend, Germanus, some years

his senior. In Bethlehem Cassian and Germanus assumed the obligations of

the monastic life, but, as in the case of many of their contemporaries,

the desire of acquiring the science of sanctity from its most eminent teachers

soon drew them from their cells in Bethlehem to the Egyptian deserts. Before

leaving their first monastic home the friends promised to return as soon

as possible, but this last clause they interpreted rather broadly, as they

did not see Bethlehem again for seven years. During their absence they

visited the solitaries most famous for holiness in Egypt, and so attracted

were they by the great virtues of their hosts that after obtaining an extension

of their leave of absence at Bethlehem, they returned to Egypt, where they

remained several years longer. It was during this period of his life that

Cassian collected the materials for his two principal works, the "Institutes"

and "Conferences". From Egypt the companions came to Constantinople, where

Cassian became a favourite disciple of St. John Chrysostom. The famous

bishop of the Eastern capitol elevated Cassian to the diaconate, and placed

in his charge the treasures of his cathedral. After the second expulsion

of St. Chrysostom, Cassian was sent as an envoy to Rome by the clergy of

Constantinople, for the purpose of interesting Pope Innocent I in behalf

of their bishop. It was probably in Rome that Cassian was elevated to the

priesthood, for it is certain that on his arrival in the Eternal City he

was still a deacon. From this time Germanus is no more heard of, and of

Cassian himself, for the next decade or more, nothing is known. About 415

he was at Marseilles where he founded two monasteries, one for men, over

the tomb of St. Victor, a martyr of the last Christian persecution under

Maximian (286-305), and the other for women. The remainder of his days

were passed at, or very near, Marseilles. His personal influence and his

writings contributed greatly to the diffusion of monasticism in the West.

Although never formally canonized, St. Gregory the Great regarded him as

a saint, and it is related that Urban V (1362-1370), who had been an abbot

of St. Victor, had the words Saint Cassian engraved on the silver casket

that contained his head. At Marseilles his feast is celebrated, with an

octave, 23 July, and his name is found among the saints of the Greek Calendar.

The two principal works of Cassian deal with the cenobitic life and the

principal or deadly sins. They are entitled: "De institutis coenobiorum

et de octo principalium vitiorum remediis libri XII" and "Collationes XXIV".

The former of these was written between 420 and 429. The relation between

the two works is described by Cassian himself (Instit., II, 9) as follows:

"These books [the Institutes] . . . are mainly taken up with what belongs

to the outer man and the customs of the coenobia [i.e. Institutes of monastic

life in common]; the others [the "Collationes" or Conferences] deal rather

with the training of the inner man and the perfection of the heart." The

first four books of the "Institutes" treat of the rules governing the monastic

life, illustrated by examples from the author's personal observation in

Egypt and Palestine; the eight remaining books are devoted to the eight

principal obstacles to perfection encountered by monks: gluttony, impurity,

covetousness, anger, dejection, accidia (ennui), vainglory, and pride.

The "Conferences" contain a record of the conversations of Cassian and

Germanus with the Egyptian solitaries, the subject being the interior life.

It was composed in three parts. The first instalment (Books I-X) was dedicated

to Bishop Leontius of Fréjus and a monk (afterwards bishop) named

Helladius; the second (Books XI-XVII), to Honoratus of Arles and Eucherius

of Lyons; the third (Books XVIII-XXIV), to the "holy brothers" Jovinian,

Minervius, Leontius, and Theodore. These two works, especially the latter,

were held in the highest esteem by his contemporaries and by several later

founders of religious orders. St. Benedict made use of Cassian in writing

his Rule, and ordered selections from the "Conferences", which he called

a mirror of monasticism (speculum monasticum), to be read daily in his

monasteries. Cassiodorus also recommended the "Conferences" to his monks,

with reservations, however, relative to their author's ideas on free will.

On the other hand, the decree attributed to Pope Gelasius, "De recipiendis

et non recipiendis libris" (early sixth century), censures this work as

"apocryphal", i.e. containing erroneous doctrines. An abridgment of the

"Conference" was made by Eucherius of Lyons which we still possess (P.

L., L, 867 sqq.). A third work of Cassian, written at the request of the

Roman Archdeacon Leo, afterwards Pope Leo the Great, about 430-431, was

a defence of the orthodox doctrine against the errors of Nestorius: "De

Incarnatione Domini contra Nestorium" (P. L., L, 9-272). It appears to

have been written hurriedly, and is, consequently, not of equal value with

the other works of its author. A large part consists of proofs, drawn from

the Scriptures, of Our Lord's Divinity, and in support of the title of

Mary to be regarded as the Mother of God; the author denounces Pelagianism

as the source of the new heresy, which he regards as incompatible with

the doctrine of the Trinity.

Yet Cassian did not himself escape the suspicion of erroneous teaching;

he is in fact regarded as the originator of what, since the Middle Ages,

has been known as Semipelagianism. Views of this character attributed to

him are found in his third and fifth, but especially in his thirteenth,

"Conference". Preoccupied as he was with moral questions he exaggerated

the rôle of free will by claiming that the initial steps to salvation

were in the power of each individual, unaided by grace. The teaching of

Cassian on this point was a reaction against what he regarded as the exaggerations

of St. Augustine in his treatise "De correptione et gratia" as to the irresistible

power of grace and predestination. Cassian saw in the doctrine of St. Augustine

an element of fatalism, and while endeavouring to find a via media between

the opinions of the great bishop of Hippo and Pelagius, he put forth views

which were only less erroneous than those of the heresiarch himself. He

did not deny the doctrine of the Fall; he even admitted the existence and

the necessity of an interior grace, which supports the will in resisting

temptations and attaining sanctity. But he maintained that after the Fall

there still remained in every soul "some seeds of goodness . . . implanted

by the kindness of the Creator", which, however, must be "quickened by

the assistance of God". Without this assistance "they will not be able

to attain an increase of perfection" (Coll., XIII, 12). Therefore, "we

must take care not to refer all the merits of the saints to the Lord in

such a way as to ascribe nothing but what is perverse to human nature".

We must not hold that "God made man such that he can never will or be capable

of what is good, or else he has not granted him a free will, if he has

suffered him only to will or be capable of what is evil" (ibid.). The three

opposing views have been summed up briefly as follows: St. Augustine regarded

man in his natural state as dead, Pelagius as quite sound, Cassian as sick.

The error of Cassian was to regard a purely natural act, proceeding from

the exercise of free will, as the first step to salvation. In the controversy

which, shortly before his death, arose over his teaching, Cassian took

no part. His earliest opponent, Prosper of Aquitaine, without naming him,

alludes to him with great respect as a man of more than ordinary virtues.

Semipelagianism was finally condemned by the Council of Orange in 529.

Junilius:

Junilius ( jIounilo",

Junillus),

an African by birth, hence commonly known as Junilius Africanus. He filled

for seven years in the court of Justinian the important office of quaestor

of the sacred palace, succeeding the celebrated Tribonian (Procop. Anecd.

c. 20). Procopius tells us that Constantine, whom the Acts of the 5th general

council shew to have held the office in 553, succeeded on the death of

Junilius, which may therefore be placed a year or two earlier. Junilius,

though a layman, took great interest in theological studies. A deputation

of African bishops visiting Constantinople, one of them, PRIMASIUS of Adrumetum,

inquired of his distinguished countryman, Junilius, who among the Greeks

was distinguished as a theologian, to which Junilius replied that he knew

one Paul [PAUL OF NISIBIS], a Persian by race, who had been educated in

the school of the Syrians at Nisibis, where theology was taught by public

masters in the same systematic manner as the secular studies of grammar

and rhetoric elsewhere. Junilius had an introduction to the Scriptures

by this Paul, which, on the solicitation of Primasius, he translated into

Latin, breaking it up into question and answer. Kihn identifies this work

of Paul with that which Ebedjesu (Asseman. Bibl. Or. III. i. 87; Badger,

Nestorians, ii. 369) calls Maschelmonutho desurtho. The work of Junilius

was called "Instituta regularia divinae legis," but is commonly known as

"De partibus divinae legis," a title which really belongs only to chap.

i. It has been often printed in libraries of the Fathers (e.g. Galland,

vol. xii.; Migne, vol. lxviii.). The best ed., for which 13 MSS. were collated,

is by Prof. Kiln of W?g (Theodor von Mopsuestia, Freiburg, 1880), a work

admirable for its thorough investigations, and throwing much light on Junilius.

The introduction does not, as has been often assumed, represent an African

school of theology, but the Syrian; and Kiln conclusively shews that (although

possibly Junilius was not aware of it himself) it is all founded on the

teaching of THEODORE of Mopsuestia.

Junilius divides the books of Scripture into two classes. The first, which

alone he calls Canonical Scripture, are of perfect authority; the second

added by many are of secondary (mediae) authority; all other books are

of no authority. The first class consists of (1) Historical Books: Pentateuch,

Josh., Judg., Ruth, Sam., and Kings., and in N.T. the four Gospels and

Acts; (2) Prophetical (in which what is evidently intended for a chronological

arrangement is substituted for that more usual): Ps., Hos., Is., Jl., Am.,

Ob., Jon., Mic., Nah., Hab., Zeph., Jer., Ezk., Dan., Hag., Zech., and

Mal. (he says that John's Apocalypse is much doubted of amongst the Easterns);

(3) Proverbial or parabolic: the Prov. of Solomon and the Book of Jesus

the Son of Sirach; (4) Doctrinal: Eccles., the 14 epp. of St. Paul in the

order now usual, including Heb., I. Pet., and I. Jn. In his second class

he counts (1) Historical: Chron., Job, Esdras (no doubt including Neh.),

Judith, Est., and Macc.; (3) Proverbial: Wisdom and Cant.; (4) Doctrinal:

the Epp. of Jas., II. Pet., Jude, II. III. Jn. Lam. and Bar. were included

in Jer. Tobit is not mentioned, but is quoted in a later part of the treatise.

Kihn is no doubt right in regarding its omission as due to the accidental

error of an early transcriber; for no writer of the time would have designedly

refused to include Tobit even in his list of deuterocanonical books. Junilius

gives as a reason for not reckoning the books of the second class as canonical

that the Hebrews make this difference, as Jerome and others testify. This

is clearly incorrect with regard to several of them, and one is tempted

to think (pace Kihn) that Junilius himself added this reference to Jerome

and did not find it in his Greek original. The low place assigned to Job

and Cant. accords with the estimate formed by Theodore of Mopsuestia. Junilius

quotes as Peter's a passage from his second epistle, which he had not admitted

into his list of canonical books. He describes Ps., Eccles., and Job as

written in metre (see Bickell, Metrices Biblicae Regulae). The work of

Junilius presents a great number of other points of interest, e.g. his

answer, ii. 29, to the question how we prove the books of Scripture to

have been written by divine inspiration.

The publication of the work Kihn assigns to 551, in which year the Chronicle

of Victor Tununensis records the presence at Constantinople of the African

bishops Reparatus, Firmus, Primasius, and Verecundus. He thinks that Junilius

probably met Paul of Nisibis there as early as 543. We do not venture to

oppose the judgment of one entitled to speak with so high authority; but

we should have thought that the introduction into the West of this product

of the Nestorian school of theology took place at an earlier period of

the controversy about the Three Chapters than 551. It is not unlikely that

Primasius paid earlier visits to Constantinople than that of which we have

evidence. A commentary on Gen. i. wrongly ascribed to Junilius is now generally

attributed to Bede.

Isidore

of Seville:

Born at Cartagena, Spain, about 560; died 4 April, 636.

Isidore was the son of Severianus and Theodora. His elder brother Leander

was his immediate predecessor in the Metropolitan See of Seville; whilst

a younger brother St. Fulgentius presided over the Bishopric of Astigi.

His sister Florentina was a nun, and is said to have ruled over forty convents

and one thousand religious.

Isidore received his elementary education in the Cathedral school of Seville.

In this institution, which was the first of its kind in Spain, the trivium

and quadrivium were taught by a body of learned men, among whom was the

archbishop, Leander. With such diligence did he apply himself to study

that in a remarkably short time mastered Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Whether

Isidore ever embraced monastic life or not is still an open question, but

though he himself may never have been affiliated with any of the religious

orders, he esteemed them highly. On his elevation to the episcopate he

immediately constituted himself protector of the monks. In 619 he pronounced

anathema against any ecclesiastic who should in any way molest the monasteries.

On the death of Leander, Isidore succeeded to the See of Seville. His long

incumbency to this office was spent in a period of disintegration and transition.

The ancient institutions and classic learning of the Roman Empire were

fast disappearing. In Spain a new civilization was beginning to evolve

itself from the blending racial elements that made up its population. For

almost two centuries the Goths had been in full control of Spain, and their

barbarous manners and contempt of learning threatened greatly to put back

her progress in civilization. Realizing that the spiritual as well as the

material well-being of the nation depended on the full assimilation of

the foreign elements, St. Isidore set himself to the task of welding into

a homogeneous nation the various peoples who made up the Hispano-Gothic

kingdom. To this end he availed himself of all the resources of religion

and education. His efforts were attended with complete success. Arianism,

which had taken deep root among the Visigoths, was eradicated, and the

new heresy of Acephales was completely stifled at the very outset; religious

discipline was everywhere strengthened. Like Leander, he took a most prominent

part in the Councils of Toledo and Seville. In all justice it may be said

that it was in a great measure due to the enlightened statecraft of these

two illustrious brothers the Visigothic legislation, which emanated from

these councils, is regarded by modern historians as exercising a most important

influence on the beginnings of representative government. Isidore presided

over the Second Council of Seville, begun 13 November, 619, in the reign

of Sisebut. But it was the Fourth National Council of Toledo that afforded

him the opportunity of being of the greatest service to his county. At

this council, begun 5 December, 633, all the bishops of Spain were in attendance.

St. Isidore, though far advanced in years, presided over its deliberations,

and was the originator of most of its enactments. It was at this council

and through his influence that a decree was promulgated commanding all

bishops to establish seminaries in their Cathedral Cities, along the lines

of the school already existing at Seville. Within his own jurisdiction

he had availed himself of the resources of education to counteract the

growing influence of Gothic barbarism. His was the quickening spirit that

animated the educational movement of which Seville was the centre. The

study of Greek and Hebrew as well as the liberal arts, was prescribed.

Interest in law and medicine was also encouraged. Through the authority

of the fourth council this policy of education was made obligatory upon

all the bishops of the kingdom. Long before the Arabs had awakened to an

appreciation of Greek Philosophy, he had introduced Aristotle to his countrymen.

He was the first Christian writer to essay the task of compiling for his

co-religionists a summa of universal knowledge. This encyclopedia epitomized

all learning, ancient as well as modern. In it many fragments of classical

learning are preserved which otherwise had been hopelessly lost. The fame

of this work imparted a new impetus to encyclopedic writing, which bore

abundant fruit in the subsequent centuries of the Middle Ages. His style,

though simple and lucid, cannot be said to be classical. It discloses most

of the imperfections peculiar to all ages of transition. It particularly

reveals a growing Visigothic influence. Arevalo counts in all Isidore's

writing 1640 Spanish words.

Isidore was the last of the ancient Christian Philosophers, as he was the

last of the great Latin Fathers. He was undoubtedly the most learned man

of his age and exercised a far-reaching and immeasurable influence on the

educational life of the Middle Ages. His contemporary and friend, Braulio,

Bishop of Saragossa, regarded him as a man raised up by God to save the

Spanish people from the tidal wave of barbarism that threatened to inundate

the ancient civilization of Spain, The Eighth Council of Toledo (653) recorded

its admiration of his character in these glowing terms: "The extraordinary

doctor, the latest ornament of the Catholic Church, the most learned man

of the latter ages, always to be named with reverence, Isidore". This tribute

was endorsed by the Fifteenth Council of Toledo, held in 688.

WORKS

As a writer, Isidore was prolific and versatile to an extraordinary degree.

His voluminous writings may be truly said to constitute the first chapter

of Spanish literature. It is not, however, in the capacity of an original

and independent writer, but as an indefatigable compiler of all existing

knowledge, that literature is most deeply indebted to him. The most important

and by far the best-known of all his writings is the "Etymologiae", or

"Origines", as it is sometimes called. This work takes its name from the

subject-matter of one of its constituent books. It was written shortly

before his death, in the full maturity of his wonderful scholarship, at

the request. of his friend Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa. It is a vast storehouse

in which is gathered, systematized, and condensed, all the learning possessed

by his time. Throughout the greater part of the Middle Ages it was the

textbook most in use in educational institutions. So highly was it regarded

as a depository of classical learning that in a great measure, it superseded

the use of the individual works of the classics themselves. Not even the

Renaissance seemed to diminish the high esteem in which it was held, and

according to Arevalo, it was printed ten times between 1470 and 1529. Besides

these numerous reprints, the popularity of the "Etymologiae" gave rise

to many inferior imitations. It furnishes, abundant evidence that the writer

possessed a most intimate knowledge of the Greek and Latin poets. In all,

he quotes from one hundred and fifty-four authors, Christian and pagan.

Many of these he had read in the originals and the others he consulted

in current compilations. In style this encyclopedic work is concise and

clear and in order, admirable. Braulio, to whom Isidore sent it for correction,

and to whom he dedicated it, divided it into twenty books.

The first three of these books are taken up with the trivium and quadrivium.

The entire first book is devoted to grammar, including metre. Imitating

the example of Cassiodorus and Boethius he preserves the logical tradition

of the schools by reserving the second book for rhetoric and dialectic.

Book

four, treats of medicine and libraries;

book

five, of law and chronology;

book

six, of ecclesiastical books and offices;

book

seven, of God and of the heavenly and earthly hierarchies;

book

eight, of the Church and of the sects, of which latter he numbers no less

than sixty-eight;

book

nine, of languages, peoples, kingdoms, and official titles;

book

ten, of etymology:

book

eleven, of man;

book

twelve, of beasts and birds;

book

thirteen, of the world and its parts;

book

fourteen, of physical geography;

book

fifteen, of public buildings and roadmaking;

book

sixteen, of stones and metals;

book

seventeen, of agriculture;

book

eighteen, of the terminology of war, of jurisprudence, and public games;

book

nineteen, of ships, houses, and clothes;

book

twenty, of victuals, domestic and agricultural tools, and furniture.

In the second book, dealing with dialectic and rhetoric, Isidore is heavily

indebted to translations from the Greek by Boethius. Caelius Aurelianus

contributes generously to that part of the fourth book which deals with

medicine. Lactantius is the author most extensively quoted in the eleventh

book, concerning man. The twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth books are

largely based on the writings of Pliny and Solinus; whilst the lost "Prata"

of Suetonius seems to have inspired the general plan of the "Etymologiae",

as well as many of its details.

Similar in its general character to the "Etymologiae" is a work entitled

"Libri duo differentiarum". The two books of which it is composed are entitled

respectively, "De differentiis verborum" and "De differentiis rerum". The

former is a dictionary of synonyms, treating of the differences of words

with considerable erudition, and not a little ingenuity; the latter an

exposition of theological and ascetical ideas, dealing in particular with

the, Trinity and with the Divine and human nature of Christ. It suggests,

and probably was inspired by, a similar work of Cato's, It is supplementary

to the first two books of the "Etymologiae". The "Synonyma", or, as it

is sometimes called on account of its peculiar treatment, "Liber lamentationum",

is in a manner illustrative of the first book of the "Differentiae". It

is cast in the form of a dialogue between Man and Reason. The general burden

of the dialogue is that Man mourns the condition to which he has been reduced

through sin, and Reason comforts him with the knowledge of how he may still

realize eternal happiness. The second part of this work consists of a dissertation

on vice and virtue. The "De natura rerum" a manual of elementary physics,

was composed at the request of King Sisebut, to whom it is dedicated. It

treats of astronomy, geography, and miscellanea. It is one of Isidore's

best known books and enjoyed a wide popularity during the Middle Ages.

The authenticity of "De ordine creaturarum" has been questioned by some

critics, though apparently without good reason. Arevalo unhesitatingly

attributes it to Isidore. It deals with various spiritual and physical

questions, such as the Trinity, the consequences of sin, eternity, the

ocean, the heavens, and the celestial bodies.

The subjects of history and biography are represented by three important

works. Of these the first, "Chronicon", is a universal chronicle. In its

preface Isidore acknowledges, his indebtedness to Julius Africanus; to

St. Jerome's rendering of Eusebius; and to Victor of Tunnuna. The "Historia

de regibus Gothorum, Wandalorum, et Suevorum" concerns itself chiefly with

the Gothic kings whose conquests and government deeply influenced the civilization

of Spain. The history of the Vandals and the Suevi is treated in two short

appendixes. This work is regarded as the chief authority on Gothic history

in the West. It contains the interesting statement that the Goths descended

from Gog and Magog. Like the other Historical writings of Isidore, it is

largely based on earlier works of history, of which it is a compendium-

It has come down to us in two recensions, one of which ends at the death

of Sisebut (621), and the other continues to the fifth year of the reign

of Swintila, his successor. "De viris illustribus" is a work of Christian

biography and constitutes a most interesting chapter in the literature

of patrology. To the number of illustrious writers mentioned therein Braulio

added the name of Isidore himself. A short appendix containing a list of

Spanish theologians was added by Braulio's disciple, Ildephonsus of Toledo.

It is the continuation of the work of Gennadius, a Semipelagian priest

of Marseilles, who wrote between 467 and 480. This work of Gennadius was

in turn, but the continuation of the work of St. Jerome.

Among the scriptural and theological works of St. Isidore the following

are especially worthy of note:

"De ortu et obitu patrum qui in Scriptura laudibus efferuntur" is a work

that treats of the more notable Scriptural characters. It contains more

than one passage that, in the light of modern scholarship, is naive or

fantastic. The question of authenticity has been raised, though quite unreasonably,

concerning it.

"Allegoriae quaedam Sacrae Scripturae" treats of the allegorical significance

that attaches to the more conspicuous characters of Scripture. In all some

two hundred and fifty personalities of the Old and New Testament are thus

treated.

"Liber numerorum qui in Sanctis Scripturis occurrunt" is a curious dissertation

on the mystical significance of Scriptural numbers.

"In libros Veteris et Novi Testamenti prooemia", as its name implies, is

a general introduction to the Scriptures, with special introductions for

particular books in the Old and New Testament.

"De Veteri et Novo Testamento quastiones" consists of a series of questions

concerning the Scriptures.

"Secretorum expositiones sacramentorum, seu quaestiones in Vetus Testamentum"

is a mystical rendering of the Old Testament books, of Genesis, Exodus,

Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Josue, Judges, Kings, Esdras, and Machabees.

It is based on the writings of the early Fathers of the Church.

"De fide catholica ex Veteri et Novo Testamento, contra Judaeos" is one

of the best known and most meritorious of Isidore's works. It is of an

apologetico-polemical character and is dedicated to Florentina, his sister,

at whose request it is said to have been written. Its popularity was unbounded

in the Middle Ages, and it was translated into many of the vernaculars

of the period. It treats of the Messianic prophecies, the passing of the

Old Law, and of the Christian Dispensation. The first part deals with the

Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, and His return for the final judgment.

The second part is taken up with the unbelief of the Jews, the calling

of the Gentiles, and the passing of the Sabbath. In all, it is an appeal

to the Jews to accept Christianity.

"Sententiarum libri tres" is a compendium of moral and dogmatic theology.

Gregory the Great and St. Augustine are the most generous contributors

to its contents. The Divine attributes, creation, evil, and miscellanea

are the subjects treated in the first book. The second is of a miscellaneous

character; whilst the third deals with ecclesiastical orders, the judgment

and the chastisement of God. It is believed that this work greatly influenced

Peter Lombard in his famous "Book of Sentences",

"De ecclesiasticis officiis" is divided into two books, "De origine officiorum"

and "De origine ministrorum". In the first Isidore treats of Divine worship

and particularly the old Spanish Liturgy. It also Contains a lucid explanation

of the Holy, Eucharist. The second treats of the hierarchy of the Church

and the various states of life. In it much interesting information is to

be found concerning the development of music in general and its adaptation

to the needs of the

Ritual.

"Regula monachorum" is a manner of life prescribed for monks, and also

deals in a general way with the monastic state. The writer furnishes abundant

proof of the true Christian democracy of the religious life by providing

for the admission of men of every rank and station of life. Not even slaves

were debarred. "God", he said, "has made no difference between the soul

of the slave and that of the freedman." He insists that in the monastery

all are equal in the sight of God and of the Church.

The first edition of the works of Isidore was published in folio by Michael

Somnius (Paris, 1580). Another edition that is quite complete is based

upon the manuscripts of Gomez, with notes by Perez and Grial (Madrid, 1599).

Based largely upon the Madrid edition is that published by Du Breul (Paris,

1601; Cologne, 1617). The last edition of all the works of Isidore, which

is also regarded as the best, is that of Arevalo (7 vols., Rome, 1797-1803).

It is found in P. L., LXXXI-LXXXIV. The "De natura rerum was edited by

G. Becker (Berlin, 1857). Th. Mommsen edited the historical writings of

St. Isidore ("Mon. Germ. Hist.: Auct. antiquiss.", Berlin, 1894). Coste

produced a German translation of the "Historia de regibus Gothorum, Wandalorum

et Suevorum" (Leipzig, 1887).

Maximus

the Confessor

Ascetic and defender of Nicene Christianity, St. Maximus was born c. 580

into a noble family at Constantinople. A student of philosophy and theology,

he served as imperial secretary to Heraclius until c. 614, when Maximus

became a monk. During a Persian invasion in 626, he travelled first to

Alexandria, then to Carthage, where he debated Pyrrhus, a monothelite.

A number of African synods condemned Maximus for his insistence that Christ

had a divine will and a human will, and Martin I invited Maximus to participate

in the Lateran synod of 649. Four years later, he was arrested and tried

at his birthplace for his refusal to adhere to the Typos of Constans II,

which forbade the discussion of Christ's will or wills. Maximus was tortured

and exile to Shemarum on the Black Sea, where he died of his injuries.

Maximus preaches that Christ's Incarnation is the purpose of history because

it restores the equilibrium destroyed by Adam's fall. If Christ is not

fully God and fully man, argues Maximus, salvation is void. Maximus is

the author of Four Centuries of Love, about asceticism and charity in daily

life; Ambigua about the writings of St. Gregory the Theologian; and Mystagogia

about the nature of the church. Maximus also commented on the works of

Dionysios the Areopagite and on the Scriptures.

Ambrose

Autpert

An early medieval writer and abbot of the Benedictine Order, born in France,

early in the eighth century; died after an abbacy of little more than a

year at his monastery of St. Vincent on the Volturno, near Beneventum,

in Southern Italy, 778 or 779. Autpert, if forgotten today, was not without

a name in his own century. Charlemagne made use of his talents; Pope Stephen

IV protected him; and the monastery where he spent many years, and of which

he died abbot was famous among the great monasteries of Italy. He has sometimes

been confounded with another Autpert who was Abbot of Monte Cassino in

the next century, and who left a collection of sermons besides a spiritual

treatise. His chief work is Expositio in Apocalypsim (P.L., XXXV, col.

2417-52).

Beatus

of Liébana

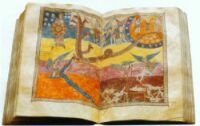

More than a thousand years before the start of the nuclear age, a diligent

monk named Beatus from Liebana, nestled in the Cantabrian mountains of

northern Spain, spent long hours pulling together page after page of words

and pictures about the destruction of the world. Beatus' Commentary on

the Apocalypse comprised writings of earlier Christians such as St. Augustine,

St. Gregory, and Tyconius of North Africa. It included illustrations based

on the Bible's last book, Revelation: men assaulted by lion-headed locusts,

angels pouring blood and hail from the heavens, the Antichrist and his

army attacking Jerusalem.

Why did Beatus of Liebana go to so much trouble to assemble these images

of apocalyptic horror? Historians and biblical scholars from the ninth

century to the present have long assumed that Beatus was hoping to rally

a Christian response to the Muslim invasion of Spain in 711, as if the

invasion, indeed, signaled the impending Armageddon. But Distinguished

Service professor John Williams, who has studied the text for 14 years,

doubts this theory. First of all, he says, the mountains protected Liebana

from the Muslim invasion. "And there's no mention of the Muslims anywhere

in the text," he adds. Williams believes that Beatus had calculated that

the world would end in the year 800 and, as a spiritual leader, felt responsible

for people's salvation. "Beatus was writing a manual of warning," Williams

concludes, "a manual instructing people how to prepare for the end of the

world."

Since the year 800 came and went without a tremor, you might expect Beatus'

book to have fallen into disrepute. But monks in Spain and France, recognizing

the biblical references in the text, believed it was God's prophesy--that

Beatus had the right message but the wrong timing. Driven by similar religious

duty, they labored to produce exact replicas of the manuscript.

"In the course of four centuries," explains Williams, "the monks never

changed a word of the text, and they never introduced changes into the

composition of the pictures." (Apocolypse

Now? By Alan Friedman)

Aldhelm of Mahnesbury

Bede

Historian and Doctor of the Church, born 672 or 673; died 735. In the last

chapter of his great work on the "Ecclesiastical History of the English

People" Bede has told us something of his own life, and it is, practically

speaking, all that we know. His words, written in 731, when death was not

far off, not only show a simplicity and piety characteristic of the man,

but they throw a light on the composition of the work through which he

is best remembered by the world at large. He writes:

Thus much concerning the ecclesiastical history of Britain, and especially

of the race of the English, I, Baeda, a servant of Christ and a priest

of the monastery of the blessed apostles St. Peter and St. Paul, which

is at Wearmouth and at Jarrow (in Northumberland), have with the Lord's

help composed so far as I could gather it either from ancient documents

or from the traditions of the elders, or from my own knowledge. I was born

in the territory of the said monastery, and at the age of seven I was,

by the care of my relations, given to the most reverend Abbot Benedict

[St. Benedict Biscop], and afterwards to Ceolfrid, to be educated. From

that time I have spent the whole of my life within that monastery, devoting

all my pains to the study of the Scriptures, and amid the observance of

monastic discipline and the daily charge of singing in the Church, it has

been ever my delight to learn or teach or write. In my nineteenth year

I was admitted to the diaconate, in my thirtieth to the priesthood, both

by the hands of the most reverend Bishop John [St. John of Beverley], and

at the bidding of Abbot Ceolfrid. From the time of my admission to the

priesthood to my present fifty-ninth year, I have endeavored for my own

use and that of my brethren, to make brief notes upon the holy Scripture,

either out of the works of the venerable Fathers or in conformity with

their meaning and interpretation.

After

this Bede inserts a list or Indiculus, of his previous writings and finally

concludes his great work with the following words:

And

I pray thee, loving Jesus, that as Thou hast graciously given me to drink

in with delight the words of Thy knowledge, so Thou wouldst mercifully

grant me to attain one day to Thee, the fountain of all wisdom and to appear

forever before Thy face.

It is plain from Bede's letter to Bishop Egbert that the historian occasionally

visited his friends for a few days, away from his own monastery of Jarrow,

but with such rare exceptions his life seems to have been one peaceful

round of study and prayer passed in the midst of his own community. How

much he was beloved by them is made manifest by the touching account of

the saint's last sickness and death left us by Cuthbert, one of his disciples.

Their studious pursuits were not given up on account of his illness and

they read aloud by his bedside, but constantly the reading was interrupted

by their tears. "I can with truth declare", writes Cuthbert of his beloved

master, "that I never saw with my eyes or heard with my ears anyone return

thanks so unceasingly to the living God." Even on the day of his death

(the vigil of the Ascension, 735) the saint was still busy dictating a

translation of the Gospel of St. John. In the evening the boy Wilbert,

who was writing it, said to him: "There is still one sentence, dear master,

which is not written down." And when this had been supplied, and the boy

had told him it was finished, "Thou hast spoken truth", Bede answered,

"it is finished. Take my head in thy hands for it much delights me to sit

opposite any holy place where I used to pray, that so sitting I may call

upon my Father." And thus upon the floor of his cell singing, "Glory be

to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Ghost" and the rest, he peacefully

breathed his last breath.

The title Venerabilis seems to have been associated with the name of Bede

within two generations after his death. There is of course no early authority

for the legend repeated by Fuller of the "dunce-monk" who in composing

an epitaph on Bede was at a loss to complete the line: Hac sunt in fossa

Bedae . . . . ossa and who next morning found that the angels had filled

the gap with the word venerabilis. The title is used by Alcuin, Amalarius

and seemingly Paul the Deacon, and the important Council of Aachen in 835

describes him as venerabilis et modernis temporibus doctor admirabilis

Beda. This decree was specially referred to in the petition which Cardinal

Wiseman and the English bishops addressed to the Holy See in 1859 praying

that Bede might be declared a Doctor of the Church. The question had already

been debated even before the time of Benedict XIV, but it was only on 13

November, 1899, that Leo XIII decreed that the feast of Venerable Bede

with the title of Doctor Ecclesiae should be celebrated throughout the

Church each year on 27 May. A local cultus of St. Bede had been maintained

at York and in the North of England throughout the Middle Ages, but his

feast was not so generally observed in the South, where the Sarum Rite

was followed.

Bede's influence both upon English and foreign scholarship was very great,

and it would probably have been greater still but for the devastation inflicted

upon the Northern monasteries by the inroads of the Danes less than a century

after his death. In numberless ways, but especially in his moderation,

gentleness, and breadth of view, Bede stands out from his contemporaries.

In point of scholarship he was undoubtedly the most learned man of his

time. A very remarkable trait, noticed by Plummer (I, p. xxiii), is his

sense of literary property, an extraordinary thing in that age. He himself

scrupulously noted in his writings the passages he had borrowed from others

and he even begs the copyists of his works to preserve the references,

a recommendation to which they, alas, have paid but little attention. High,

however, as was the general level of Bede's culture, he repeatedly makes

it clear that all his studies were subordinated to the interpretation of

Scripture. In his "De Schematibus" he says in so many words: "Holy Scripture

is above all other books not only by its authority because it is Divine,

or by its utility because it leads to eternal life, but also by its antiquity

and its literary form" (positione dicendi). It is perhaps the highest tribute

to Bede's genius that with so uncompromising and evidently sincere a conviction

of the inferiority of human learning, he should have acquired so much real

culture. Though Latin was to him a still living tongue, and though he does

not seem to have consciously looked back to the Augustan Age of Roman Literature

as preserving purer models of literary style than the time of Fortunatus

or St. Augustine, still whether through native genius or through contact

with the classics, he is remarkable for the relative purity of his language,

as also for his lucidity and sobriety, more especially in matters of historical

criticism. In all these respects he presents a marked contrast to St. Aldhelm

who approaches more nearly to the Celtic type.

WRITINGS

AND EDITIONS

No adequate edition founded upon a careful collation of manuscripts has

ever been published of Bede's works as a whole. The text printed by Giles

in 1884 and reproduced in Migne (XC-XCIV) shows little if any advance on

the basic edition of 1563 or the Cologne edition of 1688. It is of course

as an historian that Bede is chiefly remembered. His great work, the "Historia

Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum", giving an account of Christianity in England

from the beginning until his own day, is the foundation of all our knowledge

of British history and a masterpiece eulogized by the scholars of every

age. Of this work, together with the "Historia Abbatum", and the "Letter

to Egbert", Plummer has produced an edition which may fairly be called

final (2 vols., Oxford, 1896). Bede's remarkable industry in collecting

materials and his critical use of them have been admirably illustrated

in Plummer's Introduction (pp. xliii-xlvii). The "History of the Abbots"

(of the twin monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow), the Letter to Egbert",

the metrical and prose lives of St. Cuthbert, and the other smaller pieces

are also of great value for the light they shed upon the state of Christianity

in Northumbria in Bede's own day. The "Ecclesiastical History" was translated

into Anglo-Saxon at the instance of King Alfred. It has often been translated

since, notably by T. Stapleton who printed it (1565) at Antwerp as a controversial

weapon against the Reformation divines in the reign of Elizabeth. The Latin

text first appeared in Germany in 1475; it is noteworthy that no edition

even of the Latin was printed in England before 1643. Smith's more accurate

text saw the light in 1742.

Bede's chronological treatises "De temporibus liber" and "De temporum ratione"

also contain summaries of the general history of the world from the Creation

to 725 and 703, respectively. These historical portions have been satisfactorily

edited by Mommsen in the "Monumenta Germaniae historica" (4to series, 1898).

They may be counted among the earliest specimens of this type of general

chronical and were largely copied and imitated. The topographical work

"De locis sanctis" is a description of Jerusalem and the holy places based

upon Adamnan and Arculfus. Bede's work was edited in 1898 by Geyer in the

"Itinera Hierosolymitana" for the Vienna "Corpus Scriptorum". That Bede

compiled a Martyrologium we know from his own statement. But the work attributed

to him in extant manuscripts has been so much interpolated and supplemented

that his share in it is quite uncertain.

Bede's exegetical writings both in his own idea and in that of his contemporaries

stood supreme in importance among his works, but the list is long and cannot

fully be given here. They included a commentary upon the Pentateuch as

a whole as well as on selected portions, and there are also commentaries

on the Books of Kings, Esdras, Tobias, the Canticles, etc. In the New Testament

he has certainly interpreted St. Mark, St. Luke, the Acts, the Canonical

Epistles, and the Apocalypse. But the authenticity of the commentary on

St. Matthew printed under his name is more than doubtful. (Plaine in "Revue

Anglo-Romaine", 1896, III, 61.) The homilies of Bede take the form of commentaries

upon the Gospel. The collection of fifty, divided into two books, which

are attributed to him by Giles (and in Migne) are for the most part authentic,

but the genuineness of a few is open to suspicion. (Morin in "Revue Bénédictine",

IX, 1892, 316.)

Various didactic works are mentioned by Bede in the list which he has left

us of his own writings. Most of these are still preserved and there is

no reason to doubt that the texts we possess are authentic. The grammatical

treatises "De arte metricâ" and "De orthographiâ" have been

adequately edited in modern times by Keil in his "Grammatici Latini" (Leipzig,

1863). But the larger works "De naturâ rerum", De temporibus", De

temporium ratione", dealing with science as it was then understood and

especially with chronology, are only accessible in the unsatisfactory texts

of the earlier editors and Giles. Beyond the metrical life of St. Cuthbert

and some verses incorporated in the Ecclesiastical History" we do not possess

much poetry that can be assigned to Bede with confidence, but, like other

scholars of his age, he certainly wrote a good deal of verse. He himself

mentions his "book of hymns" composed in different meters or rhythms. So

Alcuin says of him: Plurima versifico cecinit quoque carmina plectro. It

is possible that the shorter of the two metrical calendars printed among

his works is genuine. The Penitential ascribed to Bede, though accepted

as genuine by Haddan and Stubbs and Wasserschleben, is probably not his

(Plummer, I, 157).

Venerable Bede is the earliest witness of pure Gregorian tradition in England.

His works "Musica theoretica" and "De arte Metricâ" (Migne, XC) are

found especially valuable by present-day scholars engaged in the study

of the primitive form of the chant.

In an era saturated with turmoil and upheaval, it comes as no surprise

that not much advance came in the field of biblical studies. The above

mentioned individuals were, for the most part, fortunate to live on the

fringe of this political and military chaos. Thus they were able to contribute

writings, which allow us some insight into their exegetical methodology.

Yet, life in general during this period was filled with troubles and hardships.

Their writings reflect this and are borne out of it.

2.1.3.2

From 800 to about 1150, Early Middle Ages

Assigned Readings for This Topic:

Gerald Bray, Biblical Interpretation: Past and Present, relevant

sections in this chapter.

Resource Materials to also be studied:

Prof. Bray's characterization of this

period, p. 132:

This

was the Early Middle Ages, when western Eruope began to forge a new culture

and civilization. After about 1000 there was increasing stability, and

centres of learning developed. A new scholarship came into being in the

monasteries, and important schools were established, in which biblical

exegesis was taught. These schools were attached to monasteries, and later

to cathedrals. At first there was little originality in all of this, but

that too appeared with time. By about 1150 western Europe was ready for

intellectual take-off, and the golden age known as the High Middle Ages

began.

Bray (p. 135-140) lists several individuals

who form the core of intellectual expression in biblical studies during

this period.

Aleuin of York (fl. c. 796 - c. 804)

Claudius of Turin (d. c. 827)

Haimo of Auixerre (d. c. 855)

Rabanus Maurus (c. 776-856)

Paschasius Radbertus (d. 865)

John Scotus Eriugena (d. c. 877)

Remigius of Auxerre (d. 908)

Fulbert of Chartres (d. 1028)

Bruno of Würzburg (c. 1005-45)

Peter Damian (d. 1072)

Othlo of St Emmeran (d. c. 1073)

Berungar of Tours (d. 1088)

Bruno the Carthusian (c. 1030 - 1101)

Anselm (d. 1117) and Ralph (d. 1134 or

1136) of Laon

Anselm

of Cantebury (1033-1109)

Life

The father of medieval scholasticism and one of the most eminent of English

prelates was born at Aost Piedmont in 1033. Anselm died at Canterbury,

England on April 21, 1109. While a boy he wished to be a monk, but his

father forbade it. When he was about twenty-three Anselm left home to live

in Burgundy and France. After three years he went to Bec in Normandy where

his celebrated countryman, Lanfranc, was prior. Here he became a monk (1060).

He succeeded Lanfranc as prior in 1063, and became abbot in 1078. The abbey

had possessions in England, which called Anselm frequently to that country.

He was the general choice for archbishop of Canterbury when Lanfranc died

(1089). However, the king, William Rufus, preferred to keep the office

vacant, and apply its revenues to his own use. In 1093 William fell ill

and, literally forced Anselm to receive an appointment at his hands. He

was consecrated December 4 of that year. The next four years witnessed

a continual struggle between king and archbishop over money matters, rights,

and privileges. Anselm wished to carry his case to Rome, and in 1097, with

much difficulty, obtained permission from the king to go. At Rome he was

honored and flattered, but he obtained little practical help in his struggle

with the king. He returned to England as soon is he heard of the death

of William in 1100. But a difficulty arose over lay investiture and homage

from clerics for their benefices. Thought a mild and meek man, Anselm had

adopted the Gregorian views of the relation between Church and State, and

adhered to them with the steadiness of conscientious conviction. The king,

though inclined to be conciliatory, was equally firm from motives of self-interest.

He had a high regard for Anselm, always treated him with much consideration,

and personal relations between them were generally friendly. Nevertheless

there was much vexatious disputing, several fruitless embassies were sent

to Rome, and Anselm himself went thither in 1103, remaining abroad till

1106. His quarrel with the king was settled by compromise in 1107 and the

brief remaining period of his life was peaceful. He was canonized in 1494.

Philosophical

Writings

As a metaphysician Anselm was a realist, and one of his earliest works,

De

fide Trinitatis, was an attack on the doctrine of the Trinity as expounded

by the nominalist Roscelin. His most celebrated works are the Monologium

and Proslogium, both aiming to prove the existence and nature of

God. The Cur deus homo, in which he develops views of atonement and satisfaction

which are still held by orthodox theologians. The two first named were

written at Bec. The last was begun in England " in great tribulation of

heart," and finished at Schiavi, a mountain villaffe of Apulia, where Anselm

enjoyed a few months of rest in 1098. His meditations and prayers are edifying

and often highly impressive. In the Monologium he argues that from the

idea of being there follows the idea of a highest and absolute, i.e. self-existent

Being, from which all other being derives its existences revival of the

ancient cosmological argument.

In the Proslogium the idea of the perfect being-" than which nothing

greater can be thought "-cannot be separated from its existence. For if

the idea of the perfect Being, thus present in consciousness, lacked existence,

a still more perfect Being could be thought, of which existence would be

a necessary metaphysical predicate, and thus the most perfect Being would

be the absolutely Real. In its most simple form, this first version of

the ontological argument is as follows:

-

The term

"God" is defined as the greatest conceivable being

-

Real existence

(existence in reality) is greater than mere existence in the understanding

-

Therefore,

God must exist in reality, not just in the understanding.

Anselm's main intuition is that the greatest possible being has every attribute

which could make it great or good. Existence in reality is one such attribute.

Anselm's actual argument is more complex than this, and is often reconstructed

as a reductio ad absurdum (reduction to absurdity). Reductio arguments

have two parts: a target argument, and a concluding argument which reduces

the target argument to absurdity. His argument begins with some general

assumptions which include the idea that (a) God exists in the understanding

(b) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding

alone. The first assumption simply means that we understand and can consistently

think about the concept of God (whereas we could not think about the concept

of a square circle, for instance). The second means that a real x is greater

than an imaginary or merely conceived x (e.g. a real $100 is greater than

an imaginary $100). Gaunilo, a contemporary monk of Anselm, wrote an attack

on Anselm's argument titled "on behalf of the fool." He offers several

criticisms, the most well known is a parody on Anselm's argument in which

he proves the existence of the greatest possible island. If we replaced

"an island than which none greater can be conceived" for "something than

which nothing greater can be conceived" then we would prove the existence

of that island. Gaunilo's point was that we could prove the existence of

almost anything using Anselm's style of argument. The ontological argument

is therefore unsound.

Theology

The key to Anselm's theory of the Atonement was the idea of "satisfaction."

In justice to himself and to the creation, God, whose honor had suffered

injury by man's sin, must react against it either by punishing men, or,

since he was merciful, the death of the God-man, which will more than compensate

for the injury to his honor, on the ground of which lie forgives sin. Incidental

features of his theory are 1) sin as a violation of a private relation

between God and man, 2) the interaction of the divine righteousness and

grace, and 3) the necessity of a representative suffering. In the Reformed

doctrine, sin and the Atonement took on more of a public character, the

active obedience of Christ was also emphasized, and the representative

relation of Christ to the law brought to the front. In the seventeenth

century the forensic and penal justice of God came into prominence. Christ

was conceived of as suffering the punishment of our sin,-a complete equivalent

of the punishment which we must have suffered, -on the ground of which

our guilt and punishment are pardoned. In the following century, Owen held

that the sufferings of Christ for sinners were not tantident but idein.

In more recent discussions along this line, Hodge maintains that Christ

suffered neither the kind nor degree of that which sinners must have suffered,

but any kind and degree of suffering which is judicially inflicted in satisfaction

of justice and law. There has indeed been no theory of the work of Christ

which has not conceived of it is a satisfaction. Even the so-called moral

influence theories center in this idea. It is therefore evident how fundamental

is the idea of satisfaction presented by Anselm. Only it must be observed

first that in the evolution of the Christian doctrine of salvation the

particular way in which the satisfaction was realized has been differently

conceived; and secondly, if the forgiveness of sin in Jesus Christ takes

place only when the ethical nature of God is satisfied, the special form

in which the satisfaction is accomplished is of subordinate importance.

In one class of views-the representative or juridical-the satisfaction

was conditioned on a unique and isolated divine-human deed-the death or

the life and death of Christ; in the other theories, the satisfaction is

threefold in the expression of the divine good-will, through the life and

death of Christ, in the initial response of sinners to forgiving grace,

and in the final bringing of all souls to perfect union with the Father.

Bruno of Asti or Segni (d. 1123)

Guibert of Nogent (1053-1124)

Rupert of Deutz (1070-c.1129)

Hugo of St Victor (c. 1096-1141)

Peter

Abelard (1079-1142)

Dialectician, philosopher, and theologian, born 1079; died 1142. Peter

Abelard (also spelled Abeillard, Abailard, etc., while the best manuscripts

have Abaelardus) was born in the little village of Pallet, about ten miles

east of Nantes in Brittany. His father, Berengar, was lord of the village,

his mother's name was Lucia; both afterwards entered the monastic state.

Peter, the oldest of their children, was intended for a military career,

but, as he himself tells us, he abandoned Mars for Minerva, the profession

of arms for that of learning. Accordingly, at an early age, he left his

father's castle and sought instruction as a wandering scholar at the schools

of the most renowned teachers of those days. Among these teachers was Roscelin

the Nominalist, at whose school at Locmenach, near Vannes, Abelard certainly

spent some time before he proceeded to Paris. Although the University of

Paris did not exist as a corporate institution until more than half a century

after Abelard's death, there flourished at Paris in his time the Cathedral

School, the School of Ste. Geneviève, and that of St. Germain des

Pré, the forerunners of the university schools of the following

century. The Cathedral School was undoubtedly the most important of these,

and thither the young Abelard directed his steps in order to study dialectic

under the renowned master (scholasticus) William of Champeaux. Soon, however,

the youth from the province, for whom the prestige of a great name was

far from awe-inspiring, not only ventured to object to the teaching of

the Parisian master, but attempted to set up as a rival teacher. Finding

that this was not an easy matter in Paris, he established his school first

at Melun and later at Corbeil. This was, probably, in the year 1101. The

next couple of years Abelard spent in his native place "almost cut off

from France", as he says. The reason of this enforced retreat from the

dialectical fray was failing health. On returning to Paris, he became once

more a pupil of William of Champeaux for the purpose of studying rhetoric.

When William retired to the monastery of St. Victor, Abelard, who meantime

had resumed his teaching at Melun, hastened to Paris to secure the chair

of the Cathedral School. Having failed in this, he set up his school in

Mt. Ste. Genevieve (1108). There and at the Cathedral School, in which

in 1113 he finally succeeded in obtaining a chair, he enjoyed the greatest

renown as a teacher of rhetoric and dialectic. Before taking up the duty

of teaching theology at the Cathedral School, he went to Laon where he

presented himself to the venerable Anselm of Laon as a student of theology.

Soon, however, his petulant restiveness under restraint once more asserted

itself, and he was not content until he had as completely discomfited the

teacher of theology at Laon as he had successfully harassed the teacher

of rhetoric and dialectic at Paris. Taking Abelard's own account of the

incident, it is impossible not to blame him for the temerity which made

him such enemies as Alberic and Lotulph, pupils of Anselm, who, later on,

appeared against Abelard. The "theological studies" pursued by Abelard

at Laon were what we would nowadays call the study of exegesis.

There can be no doubt that Abelard's career as a teacher at Paris, from

1108 to 1118, was an exceptionally brilliant one. In his "Story of My Calamities"

(Historia Calamitatum) he tells us how pupils flocked to him from every

country in Europe, a statement which is more than corroborated by Ihe authority

of his contemporaries. He was, In fact, the idol of Paris; eloquent, vivacious,

handsome, possessed of an unusually rich voice, full of confidence in his

own power to please, he had, as he tells us, the whole world at his feet.

That Abelard was unduly conscious of these advantages is admitted by his

most ardent admirers; indeed, in the "Story of My Calamities," he confesses

that

at that period of his life he was filled with vanity and pride. To these

faults he attributes his downfall, which was as swift and tragic as was

everything, seemingly, in his meteoric career. He tells us in graphic language

the tale which has become part of the classic literature of the love-theme,

how he fell in love with Heloise, niece of Canon Fulbert; he spares us

none of the details of the story, recounts all the circumstances of its

tragic ending, the brutal vengeance of the Canon, the flight of Heloise

to Pallet, where their son, whom he named Astrolabius, was born, the secret

wedding, the retirement of Heloise to the nunnery of Argenteuil, and his

abandonment of his academic career. He was at the time a cleric in minor

orders, and had naturally looked forward to a distinguished career as an

ecclesiastical teacher. After his downfall, he retired to the Abbey of

St. Denis, and, Heloise having taken the veil at Argenteuil, he assumed

the habit of a Benedictine monk at the royal Abbey of St. Denis. He who

had considered himself "the only surviving philosopher in the whole world"

was willing to hide himself -- definitely, as he thought -- in monastic

solitude. But whatever dreams he may have had of final peace in his monastic

retreat were soon shattered. He quarrelled with the monks of St. Denis,

the occasion being his irreverent criticism of the legend of their patron

saint, and was sent to a branch institution, a priory or cella, where,

once more, he soon attracted unfavourable attention by the spirit of the

teaching which he gave in philosophy and theology. "More subtle and more

learned than ever", as a contemporary (Otto of Freising) describes him,

he took up the former quarrel with Anselm's pupils. Through their influence,

his orthodoxy, especially on the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, was impeached,

and he was summoned to appear before a council at Soissons, in 1121, presided

over by the papal legate, Kuno, Bishop of Praneste. While it is not easy

to determine exactly what took place at the Council, it is clear that there

was no formal condemnation of Abelard's doctrines, but that he was nevertheless

condemned to recite the Athanasian Creed, and to burn his book on the Trinity.

Besides, he was sentenced to imprisonment in the Abbey of St. Médard,

at the instance apparently, of the monks of St. Denis, whose enmity, especially

that of their Abbot Adam, was unrelenting. In his despair, he fled to a

desert place in the neighbourhood of Troyes. Thither pupils soon began

to flock, huts and tents for their reception were built, and an oratory

erected, under the title "The Paraclete", and there his former success

as a teacher was renewed.

After the death of Adam, Abbot of St. Denis, his successor, Suger, absolved

Abelard from censure, and thus restored him to his rank as a monk. The

Abbey of St. Gildas de Rhuys, near Vannes, on the coast of Brittany, having

lost its Abbot in 1125, elected Abelard to fill his place. At the same

time, the community of Argenteuil was dispersed, and Heloise gladly accepted

the Oratory of the Paraclete, where she became Abbess. As Abbot of St.

Gildas, Abelard had, according to his own account, a very troublesome time.

The monks, considering him too strict, endeavoured in various ways to rid

themselves of his rule, and even attempted to poison him. They finally

drove him from the monastery. Retaining the title of Abbot, he resided

for some time in the neighbourhood of Nantes and later (probably in 1136)

resumed his career as teacher at Paris and revived, to some extent, the

renown of the days when, twenty years earlier, he gathered "all Europe"

to hear his lectures. Among his pupils at this time were Arnold of Brescia

and John of Salisbury. Now begins the last act in the tragedy of Abelard's

life, in which St. Bernard plays a conspicuous part. The monk of Clairvaux,

the most powerful man in the Church in those days, was alarmed at the heterodoxy

of Abelard's teaching, and questioned the Trinitarian doctrine contained

in Abelard's writings. There were admonitions on the one side and defiances

on the other; St. Bernard, having first warned Abelard in private, proceeded

to denounce him to the bishops of France; Abelard, underestimating the

ability and influence of his adversary, requested a meeting, or council,

of bishops, before whom Bernard and he should discuss the points in dispute.

Accordingly, a council was held at Sens (the metropolitan see to which

Paris was then suffragan) in 1141. On the eve of the council a meeting

of bishops was held, at which Bernard was present, but not Abelard, and

in that meeting a number of propositions were selected from Abelard's writings,

and condemned. When, on the following morning, these propositions were

read in solemn council, Abelard, informed, so it seems, of the proceedings

of the evening before, refused to defend himself, declaring that he appealed

to Rome. Accordingly, the propositions were condemned, but Abelard was

allowed his freedom. St. Bernard now wrote to the members of the Roman

Curia, with the result that Abelard had proceeded only as far as Cluny

on his way to Rome when the decree of Innocent II confirming the sentence

of the Council of Sens reached him. The Venerable Peter of Cluny now took

up his case, obtained from Rome a mitigation of the sentence reconciled

him with St. Bernard, and gave him honourable and friendly hospitality

at Cluny. There Abelard spent the last years of his life, and there at

last he found the peace which he had elsewhere sought in vain. He donned

the habit of the monks of Cluny and became a teacher in the school of the

monastery. He died at Chalôn-sur-Saône in 1142, and was buried

at the Paraclete. In 1817 his remains and those of Heloise were transferred

to the cemetery of Père la Chaise, in Paris, where they now rest.

For our knowledge of the life of Abelard we rely chiefly on the "Story

of My Calamities", an autobiography written as a letter to a friend, and

evidently intended for publication. To this may be added the letters of

Abelard and Heloise, which were also intended for circulation among Abelard's

friends. The "Story" was written about the year 1130, and the letters during

the following five or six years. In both the personal element must of course,

be taken into account. Besides these we have very scanty material; a letter

from Roscelin to Abelard, a letter of Fulco of Deuil, the chronicle of

Otto of Freising, the letters of St. Bernard, and a few allusions in the

writings of John of Salisbury. Abelard's philosophical works are "Dialectica,"

a logical treatise consisting of four books (of which the first is missing);

"Liber Divisionum et Definitionum" (edited by Cousin as a fifth book of

the "Dialectica"); Glosses on Porphyry, Boëius, and the Aristotelian

"Categories"; "Glossulae in Porphyrium" (hitherto unpublished except in

a French paraphrase by Rémusat); the fragment "De Generibus et Speciebus",

ascribed to Abelard by Cousin; a moral treatise "Scito Teipsum, seu Ethica",

first published by Pez in "Thes. Anecd. Noviss". All of these, with the

exception of the "Glossulae" and the "Ethica", are to be found in Cousin's

"Ouvrages inédits d'Abélard" (Paris, 1836). Abelard's theological

works (published by Cousin, "Petri Abselardi Opera", in 2 vols., Paris,

1849-59, also by Migne, "Patr. Lat.", CLXXVIII) include "Sic et Non", consisting

of scriptural and patristic passages arranged for and against various theological

opinions, without any attempt to decide whether the affirmative or the

negative opinion is correct or orthodox; "Tractatus de Unitate et Trinitate

Divinâ", which was condemned at the Council of Sens (discovered and

edited by Stölzle, Freiburg, 1891); "Theologia Christiana," a second

and enlarged edition of the "Tractatus" (first published by Durand and

Martène "Thes. Nov.," 1717); "Introductio in Theologiam' (more correctly,

"Theologia"), of which the first part was published by Duchesne in 1616;

"Dialogus inter Philosophum, Judaeum, et Christianum"; "Sententiae Petri

Abaelardi", otherwise called "Epitomi Theologiae Christianae", which is

seemingly a compilation by Abelard's pupils (first published by Rheinwald,

Berlin, 1535); and several exegetical works hymns, sequences, etc. In philosophy

Abelard deserves consideration primarily as a dialectician. For him, as

for all the scholastic philosophers before the thirteenth century, philosophical

inquiry meant almost exclusively the discussion and elucidation of the

problems suggested by the logical treatises of Aristotle and the commentaries

thereon, chiefly the commentaries of Porphyry and Boëtius. Perhaps

his most important contribution to philosophy and theology is the method

which he developed in his "Sic et Non" (Yea and Nay), a method germinally