The History of the English Bible

The Beginning of the English Bible

| Early Translations | Pre-Reformation | Reformation Era | KJV | Bibliography |

4.1 Early English Translations: How did English speaking people read the Bible before the King James Version?

When one speaks of the early English translations of the Bible, the division of this topic into two time periods is dictated mostly by the form of English being used at the time of the translation. The very early translations, almost exclusively that of St. Bede in the 700s, makes use of Old English. By the time of the work of John Wycliffe in the 1300s, the form of English is Middle English.

Old English was the major form of English spoken until the 1100s when Middle English began to dominate. As the Wikipedia article describes,

Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon) is an early form of the English language that was spoken in parts of what is now England and southern Scotland between the mid-fifth century and the mid-twelfth century. It is a West Germanic language and therefore is similar to Old Frisian and Old Saxon. It is also related to Old Norse and, by extension, to modern Icelandic....This sample of text from Matthew 6:9-13 provides some indication of the language:Old English was not static, and its usage covered a period of approximately 700 years – from the Anglo-Saxon migrations that created England in the fifth century to some time after the Norman invasion of 1066, when the language underwent a major and dramatic transition. During this early period it assimilated some aspects of the languages with which it came in contact, such as the Celtic languages and the two dialects of Old Norse from the invading Vikings, who were occupying and controlling the Danelaw in northern and eastern England.

| This text of The Lord's Prayer is presented

in the standardized West Saxon literary dialect: |

|

| Fæder ure þu þe eart

on heofonum,

Si þin nama gehalgod. To becume þin rice, gewurþe ðin willa, on eorðan swa swa on heofonum. urne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us todæg, and forgyf us ure gyltas, swa swa we forgyfað urum gyltendum. and ne gelæd þu us on costnunge, ac alys us of yfele. soþlice. |

Our Father in heaven,

hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And do not bring us to the time of trial, but rescue us from the evil one. |

Middle English developed in large part from the Norman invasion of England in 1066 AD. It joined a mixture of different languages current in the British Isles until the mid to late 1400s, when another shift took place linguistically. A very helpful summation is found in the Wikipedia article on Middle English:

Middle English is the name given by historical linguistics to the diverse forms of the English language spoken between the Norman invasion of 1066 and the mid-to-late 15th century, when the Chancery Standard, a form of London-based English, began to become widespread, a process aided by the introduction of the printing press into England by William Caxton in the 1470s, and slightly later by Richard Pynson. By this time the Northumbrian dialect spoken in south east Scotland was developing into the Scots language. The language of England as spoken after this time, up to 1650, is known as Early Modern English.Toward the end of the 1300s, English became increasingly the official governmental language as well in the royal court of the king. As a result, a process of standardization of the language begins. This will lay a basic foundation for the language structure even as English continues to be used today. This sample of an early and a late middle English translation of Luke 8:1-3 provides some sense of the language and the way it evolved:Unlike Old English, which tended largely to adopt Late West Saxon scribal conventions in the immediate pre-Conquest period, Middle English as a written language displays a wide variety of scribal (and presumably dialectal) forms. It should be noted, though, that the diversity of forms in written Middle English signifies neither greater variety of spoken forms of English than could be found in pre-Conquest England, nor a faithful representation of contemporary spoken English (though perhaps greater fidelity to this than may be found in Old English texts). Rather, this diversity suggests the gradual end of the role of Wessex as a focal point and trend-setter for scribal activity, and the emergence of more distinct local scribal styles and written dialects, and a general pattern of transition of activity over the centuries which follow, as Northumbria, East Anglia and London emerge successively as major centres of literary production, with their own generic interests.

| Early Middle English Translation | Late Middle English Translation | New Revised Standard Version |

| Syððan wæs geworden þæt he ferde þurh þa ceastre and þæt castel: godes rice prediciende and bodiende. and hi twelfe mid. And sume wif þe wæron gehælede of awyrgdum gastum: and untrumnessum: seo magdalenisce maria ofþære seofan deoflu uteodon: and iohanna chuzan wif herodes gerefan: and susanna and manega oðre þe him of hyra spedum þenedon; | And it is don, aftirward Jesus made iourne bi cites & castelis prechende & euangelisende þe rewme of god, & twelue wiþ hym & summe wymmen þat weren helid of wicke spiritis & sicnesses, marie þat is clepid maudeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis wenten out & Jone þe wif off chusi procuratour of eroude, & susanne & manye oþere þat mynystreden to hym of her facultes | Soon afterwards he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. The twelve were with him, as well as some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna, the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, and Susanna, and many others, who provided for them out of their resources. |

John Wycliffe's translation (1395) of Luke 8:1-3 reflects the influence of the late middle English form of the language:

1 And it was don aftirward, and Jhesus made iourney bi citees and castels, prechynge and euangelisynge the rewme of God, and twelue with hym; 2 and sum wymmen that weren heelid of wickid spiritis and sijknessis, Marie, that is clepid Maudeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis wenten out, 3 and Joone, the wijf of Chuse, the procuratoure of Eroude, and Susanne, and many othir, that mynystriden to hym of her ritchesse.4.1.1 Pre-Reformation Translations

During this time period, when some isolated translations of the English Bible began appearing, one should remember that these translations are not made from the biblical languages text. Rather, they are translations of the Latin Vulgate into a particular form of the English language. Those who produce these translations are inside the Roman Catholic church and are very loyal to it. Their concern was to help the people on the British Isles to better understand the gospel of Christ. And, in the case of Wycliffe, to also foster an awareness of the teachings of the Bible by the laity. This was intended to create pressure on the Catholic church hierarchy to reform itself and pull the church back toward biblical based teachings.

----Before

the Middle Ages, a

few isolated efforts at translating the Vulgate into Old English occurred.

The better known work was that of St.

Bede in the early 700s. But the Latin Vulgate held such sway in the

minds of most Christians in England that there was resistance to the idea

of the Bible becoming too common for the laity. The Wikipedia

article provides a summary:

----Before

the Middle Ages, a

few isolated efforts at translating the Vulgate into Old English occurred.

The better known work was that of St.

Bede in the early 700s. But the Latin Vulgate held such sway in the

minds of most Christians in England that there was resistance to the idea

of the Bible becoming too common for the laity. The Wikipedia

article provides a summary:

Although John Wycliff is often credited with the first translation of the Bible into English, there were, in fact, many translations of large parts of the Bible centuries before Wycliff's work. Toward the end of the seventh century, the Venerable Bede began a translation of Scripture into Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon). Aldhelm (AD 640–709), likewise, translated the complete Book of Psalms and large portions of other scriptures into Old English. In the 11th century, Abbot Ælfric translated much of the Old Testament into Old English.Unfortunately, none of his translation work has survived. Consequently, we have no access to any of this in order to gain a clear sense of how he did this work.For seven or eight centuries, it was the Latin Vulgate that held sway as the common version nearest to the tongue of the people. Latin had become the accepted tongue of the Catholic Church, and there was little general acquaintance with the Bible except among the educated. During all that time, there was no real room for a further translation. Medieval England was quite unripe for a Bible in the mother tongue; while the illiterate majority were in no condition to feel the want of such a book, the educated minority would be averse to so great and revolutionary a change. When a man cannot read any writing, it really does not matter to him whether books are in current speech or not, and the majority of the people for those seven or eight centuries could read nothing at all.

These centuries added to the conviction of many that the Bible ought not to become too common, that it should not be read by everybody, that it required a certain amount of learning to make it safe reading. They came to feel that it is as important to have an authoritative interpretation of the Bible as to have the Bible itself. When the movement began to make it speak the new English tongue, it provoked the most violent opposition. Latin had been good enough for a millennium; why cheapen the Bible by a translation? There had grown up a feeling that Jerome himself had been inspired. He had been canonised, and half the references to him in that time speak of him as the inspired translator.

Criticism of his version was counted as impious and profane as criticisms of the original text could possibly have been. It is one of the ironies of history that the version for which Jerome had to fight, and which was counted a piece of impiety itself, actually became the ground on which men stood when they fought against another version, counting anything else but this very version an impious intrusion.

How early the movement for an English Bible began, it is impossible now to say. Yet the fact is that until the last quarter of the fourteenth century, there was no complete prose version of the Bible in the English language. However, there were vernacular translations of parts of the Bible in England prior to in both Anglo Saxon and Norman French.

4.1.1.2 John Wycliffe, (c.1320 – December 31, 1384)

---The

most important pre-reformation Bible translator in the English speaking

world was John Wycliffe.

Closely connected with the university at Oxford most of his adult life,

he was a part of a movement that was critical of the papacy and other practices

of the Roman Catholic Church. This has earned him the label "Morning Star

of the Reformation." Wycliffe's reformation activities are well summarized

in the Wikipedia article:

---The

most important pre-reformation Bible translator in the English speaking

world was John Wycliffe.

Closely connected with the university at Oxford most of his adult life,

he was a part of a movement that was critical of the papacy and other practices

of the Roman Catholic Church. This has earned him the label "Morning Star

of the Reformation." Wycliffe's reformation activities are well summarized

in the Wikipedia article:

It was not as a teacher or preacher that Wycliffe gained his position in history; this came from his activities in ecclesiastical politics, in which he engaged about the mid-1370s, when his reformatory work also began. In 1374 he was among the English delegates at a peace congress at Bruges. He may have been given this position because of the spirited and patriotic behavior with which in the year 1366 he sought the interests of his country against the demands of the papacy. It seems he had a reputation as a patriot and reformer; this suggests the answer to the question how he came to his reformatory ideas. [Even if older evangelical parties did not exist in England before Wycliffe, he might easily have been influenced by continental "evangelicals."]Needless to say, Wycliffe's Bible translation work was part of a much larger agenda to reform the Roman Catholic Church. In particular, his desire was to force the RCC priesthood and church back to the perceived days of poverty that he assumed characterized the ministry of Jesus and the apostles. This position became the central motivation for a movement known as the Lollards, which was both a political and religious movement demanding a return to biblical principles for the priests. One of their beliefs, which was severely opposed by the church, was that piety was the sole basis for a priest being able to administer the sacraments, not official ordination by the Church. Given the massive ownership of property and political power that the Church had over most all of Europe, such a position demanding poverty was seen as extremely dangerous. Efforts to stamp out this influence were severe, despite the popularity of Wycliffe's ideas among many of the English nobility, and people in general.The root of the Wycliffite reformatory movement must be traced to his Bible study and to the ecclesiastical-political lawmaking of his times. He was well acquainted with the tendencies of the ecclesiastical politics to which England owed its position. He had studied the proceedings of King Edward I of England, and had attributed to them the basis of parliamentary opposition to papal usurpations. He found them a model for methods of procedure in matters connected with the questions of worldly possessions and the Church. Many sentences in his book on the Church recall the institution of the commission of 1274, which caused problems for the English clergy. He considered that the example of Edward I should be borne in mind by the government of his time; but that the aim should be a reformation of the entire ecclesiastical establishment. Similar was his position on the enactments induced by the ecclesiastical politics of Edward III, with which he was well acquainted and are fully reflected in his political tracts....

The sharper the strife became [with the papacy], the more Wycliffe had recourse to his translation of Scripture as the basis of all Christian doctrinal opinion, and expressly tried to prove this to be the only norm for Christian faith. In order to refute his opponents, he wrote the book in which he endeavored to show that Holy Scripture contains all truth and, being from God, is the only authority. He referred to the conditions under which the condemnation of his 18 theses was brought about; and the same may be said of his books dealing with the Church, the office of king, and the power of the pope – all completed within the space of two years (1378-79). To Wycliffe, the Church is the totality of those who are predestined to blessedness. It includes the Church triumphant in heaven, those in purgatory, and the Church militant or men on earth. No one who is eternally lost has part in it. There is one universal Church, and outside of it there is no salvation. Its head is Christ. No pope may say that he is the head, for he can not say that he is elect or even a member of the Church.

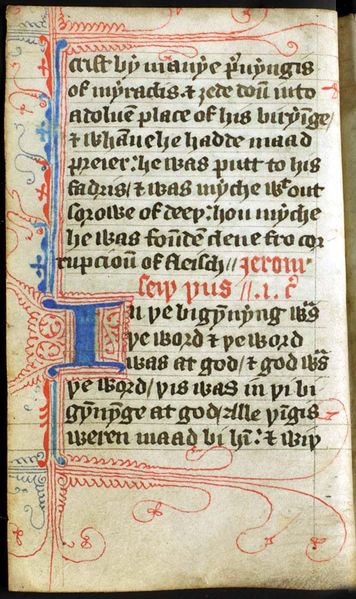

---His

translation was produced from 1380 to 1390 and released in segments

until completed and released as a whole. Increasingly, it has become clear

that others besides Wycliffe himself worked on this translation, although

it bears his name. The translation was based on the Latin Vulgate, not

the biblical language texts. The form of English was middle English. Revisions

of this translation reflect changes in wording that move it closer to the

very late forms of middle English, as the illustration below from Genesis

1:3 demonstrates:

---His

translation was produced from 1380 to 1390 and released in segments

until completed and released as a whole. Increasingly, it has become clear

that others besides Wycliffe himself worked on this translation, although

it bears his name. The translation was based on the Latin Vulgate, not

the biblical language texts. The form of English was middle English. Revisions

of this translation reflect changes in wording that move it closer to the

very late forms of middle English, as the illustration below from Genesis

1:3 demonstrates:

Vulgate: ------Dixitque Deus: Fiat lux, et facta est luxHis rendering of John 3:16 is of particular interest: For God louede so the world that he yaf his oon bigetun sone, that ech man that beliueth in him perische not, but haue euerlastynge lijf. By the completion of this translation project, Wycliffe's translation was the first English translation of the entire Bible. Thus the Wycliffe Bible marks the beginning of the English Bible.

Early Wyclif: And God said: Be made light, and made is light

Later Wyclif: And God said: Light be made; and light was made

King James:- And God said: Let there be light; and there was light

The impact of the Wycliffe translation was initially strong, but the intense opposition of the papacy and its strong-arm tactics succeeded in crushing its influence. Severe censorship laws were passed by the English parliament banning its distribution and reading. Preoccupation with wars with the French and other political eruptions pushed these religious issues to a back burner status for more than century, until Luther's movement on the European continent gained success and opened the door for translation efforts in England to flourish again.

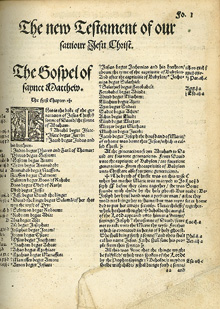

4.1.2 Reformation Era Translations

Again, the emergence of the English Bible as a complete translation with Wycliffe begins then dies. The Protestant Reformation in Europe was necessary before the English Bible could resurface, and with sufficient popularity that it successfully resisted efforts to banish it. Just as Luther had recognized the importance of a vernacular translation of the Bible into the language of the people (i.e., German), the Reformation era English Bible translators understood the same thing. By the 1500s the political atmosphere had changed, negative attitudes by both the people and political leaders against the papacy had grown -- these and other aspects created the necessary environment for the English Bible as a part of the spread of the Protestant Reformation westward across the English channel.

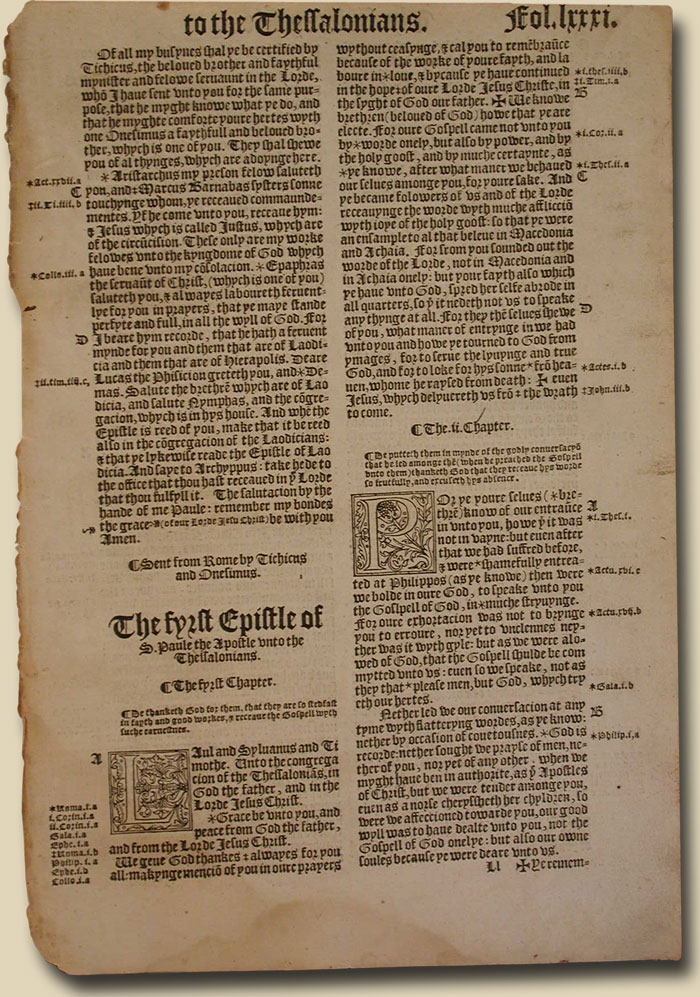

4.1.2.1 William Tyndale, c. 1494 - October 6, 1536

---Tyndale's

biography is a tale of attempted reform and adherence to biblical principles

at the cost of his life. The Wikipedia

article provides a concise summation:

---Tyndale's

biography is a tale of attempted reform and adherence to biblical principles

at the cost of his life. The Wikipedia

article provides a concise summation:

William Tyndale was born around 1494, probably in North Nibley near Dursley, Gloucestershire. The Tyndales were also known under the name "Hitchins" or "Hutchins", and it was under this name that he was educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford (now part of Hertford College), where he was admitted to the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1512 and Master of Arts in 1515. He was a gifted linguist (fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish and of course his native English) and subsequently went to Cambridge (possibly studying under Erasmus, whose 1503 Enchiridion Militis Christiani - "Handbook of the Christian Knight" - he translated into English), where he met Thomas Bilney and John Fryth.He became chaplain in the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury in about 1521. His opinions involved him in controversy with his fellow clergymen and around 1522 he was summoned before the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester on a charge of heresy. By now he had already determined to translate the Bible into English: he was convinced that the way to God was through His word and that scripture should be available even to 'a boy that driveth the plough'. He left for London.

Tyndale was firmly rebuffed in London when he sought the support of Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall. The bishop, like many highly-placed churchmen, was uncomfortable with the idea of the Bible in the vernacular. Tyndale, with the help of a merchant, Humphrey Monmouth, left England under a pseudonym and landed at Hamburg in 1524. He had already begun work on the translation of the New Testament. He visited Luther at Wittenberg and in the following year completed his translation.

Following the publication of the New Testament, Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic and demanded his arrest.

Tyndale went into hiding, possibly for a time in Hamburg, and carried on working. He revised his New Testament and began translating the Old Testament and writing various treatises. In 1530 he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, which seemed to move him briefly to the Catholic side through its opposition to Henry VIII's divorce. This resulted in the king's wrath being directed at him: he asked the emperor Charles V to have Tyndale seized and returned to England.

Eventually, he was betrayed to the authorities. He was arrested in Antwerp in 1535 and held in the castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels. He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to the stake, despite Thomas Cromwell's attempted intercession on his behalf. He was mercifully strangled, and his dead body was burnt, on 6 October 1536. His final words reportedly were: "Oh Lord, open the King of England's eyes."

----His

translation of both the Old and New Testaments is a

fascinating story intertwined with his tumultuous life:

----His

translation of both the Old and New Testaments is a

fascinating story intertwined with his tumultuous life:

Tyndale was a priest who graduated at Oxford, was a student in Cambridge when Martin Luther posted his theses at Wittenberg and was troubled by the problems within the Church. In 1523, taking advantage of the new invention of the printing machine Tyndale began to cast the Scriptures into the current English.What we continue to observe with the English Bible is that it was born in conflict and struggle against official Christianity. It continued such an existence through the work of Tyndale. But one important shift took place. Tyndale, although basically using the Latin Vulgate as his base text, did make efforts to go back to the original biblical languages of the scripture text, as limited as they were to him. Following Luther's example, the printing press was used for quick and mass reproduction of the translation. But, despite efforts to destroy it, the English Bible would survive and begin to thrive as time passed.However, Tyndale did not have copies of "original" Hebrew texts. In fact the quality of the Hebrew documents was poor, since no original Hebrew sources earlier than the 10th Century had survived. He set out to London fully expecting to find support and encouragement there, but he found neither. He found, as he once said, that there was no room in the palace of the Bishop of London to translate the New Testament; indeed, that there was no place to do it in all England. A wealthy London merchant subsidized him with the munificent gift of ten pounds, with which he went across the Channel to Hamburg; and there and elsewhere on the Continent, where he could be hid, he brought his translation to completion. Printing facilities were greater on the Continent than in England; but there was such opposition to his work that very few copies of the several editions of which we know can still be found. Tyndale was compelled to flee at one time with a few printed sheets and complete his work on another press. Several times copies of his books were solemnly burned, and his own life was frequently in danger.

The Church had objected to Tyndale's translations because in their belief purposeful mistranslations had been introduced to the works in order to promote anticlericalism and heretical views (the same argument they used against Wycliff's translation). Thomas More accused Tyndale of evil purpose in corrupting and changing the words and sense of Scripture. Specifically, he charged Tyndale with mischief in changing three key words throughout the whole of his Testament, such that "priest", "church", and "charity" of customary Roman Catholic usage became in Tyndale's translation "elder", "congregation" and "love". The Church also objected to Wycliffe and Tyndale's translations because they included notes and commentaries promoting antagonism to the Catholic Church and heretical doctrines, particularly, in Tyndale's case, Lutheranism.

There is one story which tells how money came to free Tyndale from heavy debt and prepare the way for more Bibles. The Bishop of London, Tunstall, was set on destroying copies of the English New Testament. He therefore made a bargain with a merchant of Antwerp, to secure them for him. The merchant was a friend of Tyndale, and went to him to tell him he had a customer for his Bibles, The Bishop of London. Tyndale agreed to give the merchant the Bibles to pay his debt and finance new editions of the Bible.

The original Tyndale Bible was published in Cologne in 1526. The final revision of the Tyndale translation was published in 1534. He was arrested in 1535 at Brussels, and the next year was condemned to death on charges of teaching Lutheranism. He was tied to a stake, strangled, and his body was burned. However, Tyndale may be considered the father of the King James Version (KJV) since much of his work was transferred to the KJV. The revisers of 1881 declared that while the KJV was the work of many hands, the foundation of it was laid by Tyndale, and that the versions that followed it were substantially reproductions of Tyndale's, or revisions of versions which were themselves almost entirely based on it.

The importance of Tyndale's work for the English Bible through the King James Version cannot be emphasized too much. His translation laid a path for phrases, use of certain words, and, in general, a basic tone to English language expression in Bible translation that would last for several centuries. Not until the 1950s will the English Bible begin variations from the classic translation pattern initially laid down by Tyndale. Thus the discussion of the other Reformation era English translations will to some degree be a discussion of how they vary from Tyndale's translation.

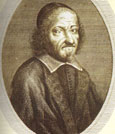

----When

one looks at the life of Miles Coverdale, there emerges a life mostly of

suffering and persecution because of his dissent from the Roman Catholic

Church of his day. Note the biographical sketch in the Wikipedia Encyclopedia:

----When

one looks at the life of Miles Coverdale, there emerges a life mostly of

suffering and persecution because of his dissent from the Roman Catholic

Church of his day. Note the biographical sketch in the Wikipedia Encyclopedia:

Myles Coverdale (also Miles Coverdale) (c. 1488 - January 20, 1568) was a 16th-century Bible translator who produced the first complete printed translation of the Bible into English.He was born probably in the district known as Cover-dale, in that district of the North Riding of Yorkshire called Richmondshire, England, 1488; died in London and buried in St. Bartholomew's Church Feb. 19, 1568.

He studied at Cambridge (bachelor of canon law 1531), became priest at Norwich in 1514 and entered the convent of Austin friars at Cambridge, where Robert Barnes was prior in 1523 and probably influenced him in favor of Protestantism. When Barnes was tried for heresy in 1526, Coverdale assisted in his defence and shortly afterward left the convent and gave himself entirely to preaching.

From 1528 to 1535, he appears to have spent most of his time on the Continent, where his Old Testament was published by Jacobus van Meteren in 1535. In 1537, some of his translations were included in the Matthew Bible, the first English translation of the complete Bible. In 1538, he was in Paris, superintending the printing of the "Great Bible," and the same year were published, both in London and Paris, editions of a Latin and an English New Testament, the latter being by Coverdale. That 1538 Bible was a diglot (dual-language) Bible, in which he compared the Latin Vulgate with his own English translation. He also edited "Cranmer's Bible" (1540).

He returned to England in 1539, but on the execution of Thomas Cromwell (who had been his friend and protector since 1527) in 1540, he was compelled again to go into exile and lived for a time at Tübingen, and, between 1543 and 1547, was a Lutheran pastor and schoolmaster at Bergzabern (now Bad Bergzabern) in the Palatinate, and very poor.

In March, 1548, he went back to England, was well received at court and made king's chaplain and almoner to the queen dowager, Catherine Parr. In 1551, he became bishop of Exeter, but was deprived in 1553 after the succession of Mary. He went to Denmark (where his brother-in-law was chaplain to the king), then to Wesel, and finally back to Bergzabern. In 1559, he was again in England, but was not reinstated in his bishopric, perhaps because of Puritanical scruples about vestments. From 1564 to 1566, he was rector of St. Magnus's, near London Bridge.

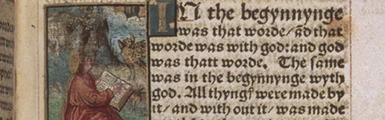

----The

examples below from the Prologue of the Gospel of John (1:1-18) provide

illustration of both the similarities and distinctives of Coverdale's work

in comparison to that of Tyndale, done less than a decade earlier:

----The

examples below from the Prologue of the Gospel of John (1:1-18) provide

illustration of both the similarities and distinctives of Coverdale's work

in comparison to that of Tyndale, done less than a decade earlier:

| William Tyndale (1526) | Miles Coverdale Bible (1535) | New Revised Standard Version |

| 1

In the beginnynge was the worde and the worde was with God: and the worde

was God. 2 The same was in the beginnynge with God. 3 All thinges were

made by it and with out it was made nothinge that was made. 4 In it was

lyfe and the lyfe was ye lyght of men 5 and the lyght shyneth in the darcknes

but the darcknes comprehended it not.

6 There was a man sent from God whose name was Iohn. 7 The same cam as a witnes to beare witnes of the lyght that all men through him myght beleve. 8 He was not that lyght: but to beare witnes of the lyght. 9 That was a true lyght which lyghteth all men that come into the worlde. 10 He was in ye worlde and the worlde was made by him: and yet the worlde knewe him not. 11 He cam amonge his (awne) and his awne receaved him not. 12 But as meny as receaved him to them he gave power to be the sonnes of God in yt they beleved on his name: 13 which were borne not of bloude nor of the will of the flesshe nor yet of the will of man: but of God. 14 And the worde was made flesshe and dwelt amonge vs and we sawe the glory of it as the glory of the only begotten sonne of ye father which worde was full of grace and verite. 15 Iohn bare witnes of him and cryed sayinge: This was he of whome I spake he that cometh after me was before me because he was yer then I. 16 And of his fulnes have all we receaved even (grace) for grace. 17 For the lawe was geven by Moses but grace and truthe came by Iesus Christ. 18 No ma hath sene God at eny tyme. The only begotte sonne which is in ye bosome of ye father he hath declared him. |

1 In the begynnynge was the worde, and the worde was with God, and God

was ye worde. 2 The same was in the begynnynge wt God. 3 All thinges were

made by the same, and without the same was made nothinge that was made.

4 In him was the life, and the life was the light of men: 5 and the light

shyneth in the darknesse, and the darknesse comprehended it not.

6 There was sent from God a man, whose name was Ihon. 7 The same came for a witnesse, to beare wytnesse of ye light, that thorow him they all might beleue. 8 He was not that light, but that he might beare witnesse of ye light. 9 That was the true light, which lighteth all men, that come in to this worlde. 10 He was in the worlde, & the worlde was made by him, and ye worlde knewe him not. 11 He came in to his awne, and his awne receaued him not. 12 But as many as receaued him, to them gaue he power to be the children of God: euen soch as beleue in his name. 13 Which are not borne of bloude, ner of the wyl of the flesh, ner of the wyl of man, but of God. 14 And the worde became flesh, and dwelt amonge vs: and we sawe his glory, a glory as of the onely begotte sonne of the father, full of grace and trueth. 15 Ihon bare wytnesse of him, cryed, and sayde: It was this, of whom I spake: After me shal he come, that was before me, For he was or euer I: 16 and of his fulnesse haue all we receaued grace for grace. 17 For the lawe was geuen by Moses, grace and trueth came by Iesus Christ. 18 No man hath sene God at eny tyme. The onely begotte sonne which is in the bosome of the father, he hath declared the same vnto vs. |

1

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word

was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God. 3 All things came into being

through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come

into being 4 in him was life, and the life was the light of all people.

5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

6 There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. 7 He came as a witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. 8 He himself was not the light, but he came to testify to the light. 9 The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world. 10 He was in the world, and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not know him. 11 He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him. 12 But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, 13 who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God. 14 And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father's only son, full of grace and truth. 15 (John testified to him and cried out, "This was he of whom I said, "He who comes after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me.'") 16 From his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. 17 The law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. 18 No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father's heart, who has made him known. |

Coverdale followed the emerging tradition of making an English translation from the Latin Vulgate, rather than from the original Hebrew and Greek texts. You don't have to look very far before the similarities of wording etc. to Tyndale's work become very clear. Fredrick G. Kenyon provides a helpful summation of the significance of Coverdale's work, particularly in relationship to that of Tyndale:

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his gift of an English Bible to his country; but during his imprisonment he may have learnt that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterwards bishop of Exeter (1551-1553). The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale abroad in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work. It was probably printed by Froschover at Zurich; but this has never been absolutely demonstrated. It was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope, and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the Kinng's most gracious license." In thus licensing Coverdale's translation, Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned. In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]His contributions as a Bible translator to several different translation beyond his own produces this observation: "It could also be said of Myles Coverdale, that he had a part in the publication of more different editions of English language Bibles in the 1500’s, than any other person in history." He lived a simple life as a good, compassionate man, first as a priest in the Catholic church and then later as a preacher of Puritanism.In one respect Coverdale's Bible was epoch-making, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the Old Testament. In the Vulgate, as is well known, the books which are now classed as Apocrypha are intermingled with the other books of the Old Testament. This was also the case with the Septuagint, and in general it may be said that the Christian church had adopted this view of the canon. It is true that many of the greatest Christian Fathers had protested against it, and had preferred the Hebrew canon, which rejects these books. The canon of Athanasius places the Apocrypha in a class apart; the Syrian Bible omitted them; Eusebius and Gregory Nazianzen appear to have held similar views; and Jerome refused to translate them for his Latin Bible. Nevertheless the church at large, both East and West, retained them in their Bibles, and the provincial Council of Carthage (A.D. 397), under the influence of Augustine, expressly included them in the canon. In spite of Jerome, the Vulgate, as it circulated in Western Europe, regularly included the disputed books; and Wyclif's Bible, being a translation from the Vulgate, naturally has them too. On the other hand, Luther, though recognizing these books as profitable and good for reading, placed them in a class apart, as "Apocrypha," and in the same way he segregated Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Apocalypse at the end of the New Testament, as of less value and authority than the rest. This arrangement appears in the table of contents of Tyndale's New Testament in 1525, and was adopted by Coverdale, Matthew, and Taverner. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive. On the other hand, the Roman Church, at the Council of Trent (1546), adopted by a majority the opinion that all the books of the larger canon should be received as of equal authority, and for the first time made this a dogma of the Church, enforced by an anathema. In 1538, Coverdale published a New Testament with Latin (Vulgate) and English in parallel columns, revising his English to bring it into conformity with the Latin; but this (which went through three editions with various changes) may be passed over, as it had no influence on the general history of the English Bible.

A couple of revisions of Coverdale's work followed his:

Matthew's Bible. This translation was made in 1537 by John Rogers, an assistant of Tyndale, under the alias Thomas Matthew. It was based entirely upon the work of Tyndale and Coverdale and it was printed under the King's License, as the third edition of Coverdale's Bible had been. Taverner's Bible. This was an unimportant revision of the Matthew's Bible appearing in 1539, the work of Richard Taverner.4.1.2.3. The Great Bible, 1539

----This

translation was produced in large part by Miles Coverdale as well. Large

portions of it were an update of the work of William Tyndale. It has the

distinction of be the first officially authorized English translation.

King Henry VIII declared it to be the official English Bible to be used

by the Church of England. The Wikipedia article effectively summarizes

this work:

----This

translation was produced in large part by Miles Coverdale as well. Large

portions of it were an update of the work of William Tyndale. It has the

distinction of be the first officially authorized English translation.

King Henry VIII declared it to be the official English Bible to be used

by the Church of England. The Wikipedia article effectively summarizes

this work:

The Great Bible was the first authorised edition of the Bible in English, authorised by King Henry VIII of England to be read aloud in the church services of the Church of England.As noted so much before, this translation depended almost entirely on the Latin Vulgate. One can't help but notice the powerful influence the Vulgate continued to exert upon Protestantism through this indirect means.The Great Bible was prepared by Myles Coverdale, working under commission of Sir Thomas Cromwell, Secretary to Henry VIII and Vicar General. In 1538, Cromwell directed the clergy to provide:

"…one book of the bible of the largest volume in English, and the same set up in some convenient place within the said church that ye have care of, whereas your parishioners may most commodiously resort to the same and read it."

The first edition was a run of 2,500 copies that were begun in Paris in 1539. Much of the printing was done at Paris, and after some misadventures where the printed sheets were seized by the French authorities on grounds of heresy (since relations between England and France were somewhat troubled at this time), the publication was completed in London in April 1539. It went through six subsequent revisions between 1540 and 1541. The second edition of 1540 included a preface by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, recommending the reading of the scriptures. (Weigle viii; Pollard 16-19.)

Although called the Great Bible because of its large size, it is known by several other names as well. It was called the Cromwell Bible, since Thomas Cromwell directed its publication. It was also termed the Cranmer Bible, since Thomas Cranmer wrote the preface as well as convinced the King to commission an authorized version. Cranmer’s preface was also included in the front of the Bishops' Bible. It was also called the Chained Bible, since it was chained in "some convenient place within the said church."

The Great Bible includes, with very slight revision, the New Testament and the Old Testament portions that had been translated by William Tyndale. The remaining books of the Old Testament were translated by Coverdale, who used mostly the Latin Vulgate and Martin Luther's German translation as sources rather than working from the original Greek and Hebrew texts.

The Great Bible's New Testament revision is chiefly distinguished from Tyndale's source version by the interpolation of numerous phrases and sentences found only in the Vulgate. For example, here is the Great Bible's version of Acts 23:24-25 (as given in The New Testament Octapla):

"...And delyver them beastes, that they maye sett Paul on, and brynge him safe unto Felix the hye debyte (For he dyd feare lest happlye the Jewes shulde take hym awaye and kyll him, and he hym selfe shulde be afterwarde blamed, as though he wolde take money.) and he wrote a letter after thys maner."

The non italicized portions are taken over from Tyndale without change, but the italicized words, which are not found in the Greek Textus Receptus used by Tyndale to translate, have been added from the Latin. (The added sentence can also be found, with minor verbal differences, in the Douai-Rheims New Testament.) These inclusions appear to have been done to make the Great Bible more palatable to conservative English churchmen, many of whom considered the Vulgate to be the only legitimate Bible.

The psalms in the Book of Common Prayer are taken from the Great Bible rather than the King James Bible.

The Great Bible was superseded as the authorised version of the Anglican Church in 1568 by the Bishops' Bible.

4.1.2.4 The Bishop's Bible, 1568

----This

version of the English Bible came about largely through the efforts of

Matthew

Parker (1504-75), the archbishop of Canterbury. It came

about after Elizabeth had ascended to the throne following the reign of

Queen Mary who attempted to crush the Church of England and return the

country to a pure Catholic commitment.

----This

version of the English Bible came about largely through the efforts of

Matthew

Parker (1504-75), the archbishop of Canterbury. It came

about after Elizabeth had ascended to the throne following the reign of

Queen Mary who attempted to crush the Church of England and return the

country to a pure Catholic commitment.

----This

translation was a reactionary Bible. That is, it attempted to stem the

tide of Calvinism being spread throughout England by the very popular Geneva

Bible (see below). Parker led a group of bishops in the Anglican

Church to produce this translation, and it was officially designated to

be read in all the worship services of the Church of England. Although

the official Bible, it never became popular among the people. King

James' "authorization" did not mandate that it replace the Bishops' Bible;

instead, this "authorization" merely permitted it to replace the Bishops'

Bible for use in the church. In reality, many bishops continued to use

the Bishops' Bible for several decades after 1611. Thus it failed to stem

the influence of the Geneva Bible. The Wikipedia

article contains a helpful summation:

----This

translation was a reactionary Bible. That is, it attempted to stem the

tide of Calvinism being spread throughout England by the very popular Geneva

Bible (see below). Parker led a group of bishops in the Anglican

Church to produce this translation, and it was officially designated to

be read in all the worship services of the Church of England. Although

the official Bible, it never became popular among the people. King

James' "authorization" did not mandate that it replace the Bishops' Bible;

instead, this "authorization" merely permitted it to replace the Bishops'

Bible for use in the church. In reality, many bishops continued to use

the Bishops' Bible for several decades after 1611. Thus it failed to stem

the influence of the Geneva Bible. The Wikipedia

article contains a helpful summation:

The thorough Calvinism of the Geneva Bible offended the high-church party of the Church of England, to which almost all of its bishops subscribed. They associated Calvinism with Presbyterianism, which sought to replace government of the church by bishops (Episcopalian) with government by lay elders. In an attempt to replace the objectionable translation, they circulated one of their own, which became known as the Bishops' Bible.4.1.2.5 The Geneva Bible, 1560The leading figure in translating was Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury. It was at his instigation that the various sections translated by Parker and his fellow bishops were followed by their initials in the early editions. For instance, at the end of the book of Deuteronomy, we find the initials "W.E.," which, according to a letter Parker wrote to Sir William Cecil, stands for William Alley, Bishop of Exeter. Parker tells Cecil that this system was "to make [the translators] more diligent, as answerable for their doings" (Pollard 22-3).

The Bishops' Bible had the authority of the royal warrant, and was the version specifically authorised to be read aloud in church services. However, it failed to displace the Geneva Bible from its popular esteem. The version was more grandiloquent than the Geneva Bible, but was harder to understand. It lacked most of the footnotes and cross-references in the Geneva Bible, which contained much controversial theology, but which were helpful to people among whom the Bible was just beginning to circulate in the vernacular. As a result, while the Bishops' Bible went through 20 editions from its introduction to 1606, during the same period the Geneva Bible was reprinted more than 150 times.

In 1611, the King James Version was published, and soon took the Bishops' Bible's place as the de facto standard of the Church of England. Later judgments of the Bishops' Bible have not been favorable; David Daniell, in his important edition of William Tyndale's New Testament, states that the Bishops' Bible "was, and is, not loved. Where it reprints Geneva it is acceptable, but most of the original work is incompetent, both in its scholarship and its verbosity" (Daniell xii).

Unlike Tyndale's translations and the Geneva Bible, the Bishops' Bible has rarely been reprinted. The most available reprinting of its New Testament portion (minus its marginal notes) can be found in the fourth column of the New Testament Octapla edited by Luther Weigle, chairman of the translation committee that produced the Revised Standard Version.

The Bishops' Bible is also known as the "Treacle Bible", due to its translation of Jeremiah 8:22 which reads "Is there not treacle at Gilead?" In the Authorized Version of 1611, "treacle" was changed to "balm".

----This

Bible was the "Puritan Bible," at least in the eyes of many Englanders.

During the reign of Queen

Mary I (1553-1558), efforts were made to forcibly bring England and

Scotland back under Roman Catholicism. Many Puritans fled to Geneva in

Switzerland for safety. Miles Coverdale was among them. In Switzerland

several of these Puritan scholars, influenced by the Reformed Church movement

led there by John Calvin

and Theodore Beza,

began a translation project to update the Great Bible.

The project began in 1557 and the first edition was released in 1560. "The

Geneva Bible was a Protestant translation of the Bible into English. It

has also been known as the Breeches Bible, after its rendering of Genesis

3:7, 'Then the eyes of them both were opened, and they knewe

that they were naked, and they sewed figge tree leaues together, and made

them selues breeches.' This was the Bible read by William Shakespeare,

by John Donne, and by John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim's Progress. It was

the Bible that was brought to America on the Mayflower and used by Oliver

Cromwell in the English Civil War. Because the language of the Geneva Bible

was more forceful and vigorous, most readers preferred this version strongly

over the Bishops' Bible, the translation authorised by the Church of England

under Elizabeth I." ("Geneva Bible," Wikipedia)

----This

Bible was the "Puritan Bible," at least in the eyes of many Englanders.

During the reign of Queen

Mary I (1553-1558), efforts were made to forcibly bring England and

Scotland back under Roman Catholicism. Many Puritans fled to Geneva in

Switzerland for safety. Miles Coverdale was among them. In Switzerland

several of these Puritan scholars, influenced by the Reformed Church movement

led there by John Calvin

and Theodore Beza,

began a translation project to update the Great Bible.

The project began in 1557 and the first edition was released in 1560. "The

Geneva Bible was a Protestant translation of the Bible into English. It

has also been known as the Breeches Bible, after its rendering of Genesis

3:7, 'Then the eyes of them both were opened, and they knewe

that they were naked, and they sewed figge tree leaues together, and made

them selues breeches.' This was the Bible read by William Shakespeare,

by John Donne, and by John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim's Progress. It was

the Bible that was brought to America on the Mayflower and used by Oliver

Cromwell in the English Civil War. Because the language of the Geneva Bible

was more forceful and vigorous, most readers preferred this version strongly

over the Bishops' Bible, the translation authorised by the Church of England

under Elizabeth I." ("Geneva Bible," Wikipedia)

Several new items would be included in this new Bible. Most importantly were:

First, it was the first English Bible to use both chapter and verse numbering, which were developed by William Whittingham, one of the translators on this project. The New Testament versification drew largely from the printed Greek text of Robert Estienne who introduced them in 1551. These have become the standard followed by all English translations since then.

Second, the Geneva Bible introduced study notes and cross-referencing systems to the English Bible. This quickly became the most controversial aspect of the translation. This objection was largely due to the very strong Calvinist and Puritan tones and doctrinal viewpoints saturating these notes. The leadership of the Church of England as well as the king vigorously objected to these notes because they contradicted Anglican theological views in many significant places. This played a major role in King James I authorizing the King James Version, the Anglican translation to counteract this influence. Additionally, the Geneva Bible spurred the Roman Catholic Church to produce its first English translation of the Bible, the Douai Bible. Gary DeMar provides additional details ("Historic Church Documents," Reformed.Org):

This introduces one of the ironies that continues to exist in many Protestant circles to this very day. The King James Version came about as a Church of England translation expressly to snub out the influence of the Geneva Bible with its Puritan beliefs that were shaped by Calvinism. Yet, many very conservative Protestant groups today with strong Calvinistic leanings will only allow the use of the King James Version of the Bible in their churches.England's Most Popular Bible While other English translations failed to capture the hearts of the reading public, the Geneva Bible was instantly popular. Between 1560 and 1644 at least 144 editions appeared. For forty years after the publication of the King James Bible, the Geneva Bible continued to be the Bible of the home. Oliver Cromwell used extracts from the Geneva Bible for his Soldier's Pocket Bible which he issued to the army.In 1620 the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth with their Bibles and a conviction derived from those Bibles of establishing a new nation. The Bible was not the King James Version. When James I became king of England in 1603, there were two translations of the Bible in use; the Geneva Bible was the most popular, and the Bishops' Bible was used for reading in churches. A THREAT TO KING JAMES

King James disapproved of the Geneva Bible because of its Calvinistic leanings. He also frowned on what he considered to be seditious marginal notes on key political texts. A marginal note for Exodus 1:9 indicated that the Hebrew midwives were correct in disobeying the Egyptian king's orders, and a note for 2 Chronicles 15:16 said that King Asa should have had his mother executed and not merely deposed for the crime of worshipping an idol. The King James Version of the Bible grew out of the king's distaste for these brief but potent doctrinal commentaries. He considered the marginal notes to be a political threat to his kingdom.

At a conference at Hampton Court in 1604 with bishops and theologians, the king listened to a suggestion by the Puritan scholar John Reynolds that a new translation of the Bible was needed. Because of his distaste for the Geneva Bible, James was eager for a new translation. "I profess," he said, "I could never yet see a Bible well translated in English; but I think that, of all, that of Geneva is the worst."

In addition to being a threat to the king of England, the Geneva Bible was outspokenly anti-Roman Catholic, as one might expect. Rome was still persecuting Protestants in the sixteenth century. Keep in mind that the English translators were exiles from a nation that was returning to the Catholic faith under a queen who was burning Protestants at the stake. The anti-Roman Catholic sentiment is most evident in the Book of Revelation: "The beast that cometh out of the bottomless pit (Rev. 11:7) is the Pope, which hath his power out of hell and cometh thence." In the end, the Geneva Bible was replaced by the King James Version, but not before it helped to settle America. A THREAT TO ROME

To help see the similarities and differences of the Geneva Bible from its predecessors and competitors, note the translations of Psalm 51:

| Great Bible | Bishop's Bible | Geneva Bible |

|

1 Have mercy upon me, O God, after thy (great) goodness: according to the

multitude of thy mercies do away mine offences. 2 Wash me throughly from

mine wickedness: and cleanse me from my sin. 3 For I knowledge my fautes:

and my sinne is ever before me. 4 Against the onely have I sinned and done

this evill in thy sighte: that thou mightest be justified in thy saiyng

and clear when thou art judged. 5 Beholde, I was shapen in wickednes, and

in syn hath my mother conceyved me. 6 But lo, thou requirest truth in the

inward partes: and shalt make mee to understande wisdom secretely.

7 Thou shalt pourge me with Hyssop, and I shalbe clean: thou shalt washe me, and I shalbe whiter then snow. 8 Thou shalt make me heare joye and gladnes: that the bones which thou hast broken, may rejoyce. 9 Turne thy face from my sinnes: and put out all my misdedes. 10 Make me a clean heart (O God) and renewe a right spirite within me. 11 Cast me not away from thy presence: and take not thy holy spirite from me. 12 O geve me the comfort of thy helpe again: and stablishe me with thy free spirite. 13 Then shall I teache thy ways unto the wicked and sinners shall be converted unto the. 14 Deliver me from bloude giltiness, O God, thou that art the God of my health: and my tongue shal sing of thy righteousnes. 15 Thou shalt open my lyppes, O Lord: my mouthe shall shew thy praise. 16 For thou desirest no sacrifice, else would I geve it thee: but thou delightest not in burnt offeringes. 17 The sacrifice of god is a troubled spirite: a broken and a contrite herte O God shalt thou not dispise. 18 O be favourable & gracious unto Sion: builde thou the walles of Jerusalem. 19 Then shalte thou be pleased with the sacrifice of righteousnes, with the burnte offerynges and oblations: then shall they offer yong bullockes upon thyne alter. |

1 Haue mercie on me O Lorde accordyng to thy louyng kindnesse: accordyng

vnto the multitudes of thy mercies wype out my wickednesse. 2 Washe me

throughly from myne iniquitie: and clense me from my sinne. 3 For I do

acknowledge my wickednesse: and my sinne is euer before me. 4 Agaynst thee,

only agaynst thee I haue sinned and done this euyll in thy sight: that

thou mightest be iustified in thy saying, and founde pure when thou art

iudged. 5 Beholde, I was ingendred in iniquitie: and in sinne my mother

conceaued me. 6 Neuerthelesse, lo thou requirest trueth in the inwarde

partes [of me]: & [therfore] thou wylt make me learne wisdome in the

secrete [part of myne heart.]

7 Purge thou me with hyssop and I shalbe cleane: washe thou me, and I shalbe whyter then snowe. 8 Make thou me to heare [some] ioy and gladnesse: let the bones reioyce which thou hast broken. 9 Turne thy face from my sinnes: and wype out all my misdeedes. 10 Make thou vnto me a cleane heart O Lorde: and renue thou a ryght spirite within me. 11 Cast me not away from thy presence: and take not thy holy spirite from me. 12 Geue me agayne the comfort of thy saluation: and confirme me with a free wyllyng spirite. 13 Then wyll I teache thy wayes vnto the wicked: and sinners shalbe conuerted vnto thee. 14 Deliuer me from blood O Lorde, the Lorde of my saluation: and my tongue shall sing with a ioyfull noyse of thy iustice. 15 O Lorde open thou my lippes: and my mouth shall set foorth thy prayse. 16 For thou desirest no sacrifice, els I would geue it thee: thou delightest not in a burnt offering. 17 Sacrifices for God is a mortified spirite: O Lorde thou wylt not despise a mortified and an humble heart. 18 Be thou beneficiall vnto Sion, according to thy gracious good wyll: buylde thou the walles of Hierusalem. 19 Then shalt thou be pleased with the sacrifices of righteousnes, with burnt offeringes and oblations: then wyll they offer young bullockes vpon thyne aulter. |

1 To him that excelleth. A Psalme of Dauid, when the Prophet Nathan came

vnto him, after he had gone in to Bath-sheba. Haue mercie vpon me, O God,

according to thy louing kindnes: according to the multitude of thy compassions

put away mine iniquities. 2 Wash me throughly from mine iniquitie, and

clense me from my sinne. 3 For I know mine iniquities, and my sinne is

euer before me. 4 Against thee, against thee onely haue I sinned, and done

euill in thy sight, that thou mayest be iust when thou speakest, and pure

when thou iudgest. 5 Beholde, I was borne in iniquitie, and in sinne hath

my mother conceiued me. 6 Beholde, thou louest trueth in the inwarde affections:

therefore hast thou taught mee wisedome in the secret of mine heart.

7 Purge me with hyssope, & I shalbe cleane: wash me, and I shalbe whiter then snowe. 8 Make me to heare ioye and gladnes, that the bones, which thou hast broken, may reioyce. 9 Hide thy face from my sinnes, and put away all mine iniquities. 10 Create in mee a cleane heart, O God, and renue a right spirit within me. 11 Cast mee not away from thy presence, and take not thine holy Spirit from me. 12 Restore to me the ioy of thy saluation, and stablish me with thy free Spirit. 13 Then shall I teache thy wayes vnto the wicked, and sinners shalbe conuerted vnto thee. 14 Deliuer me from blood, O God, which art the God of my saluation, and my tongue shall sing ioyfully of thy righteousnes. 15 Open thou my lippes, O Lorde, and my mouth shall shewe foorth thy praise. 16 For thou desirest no sacrifice, though I would giue it: thou delitest not in burnt offering. 17 The sacrifices of God are a contrite spirit: a contrite and a broken heart, O God, thou wilt not despise. 18 Bee fauourable vnto Zion for thy good pleasure: builde the walles of Ierusalem. 19 Then shalt thou accept ye sacrifices of righteousnes, euen the burnt offering and oblation: then shall they offer calues vpon thine altar. |

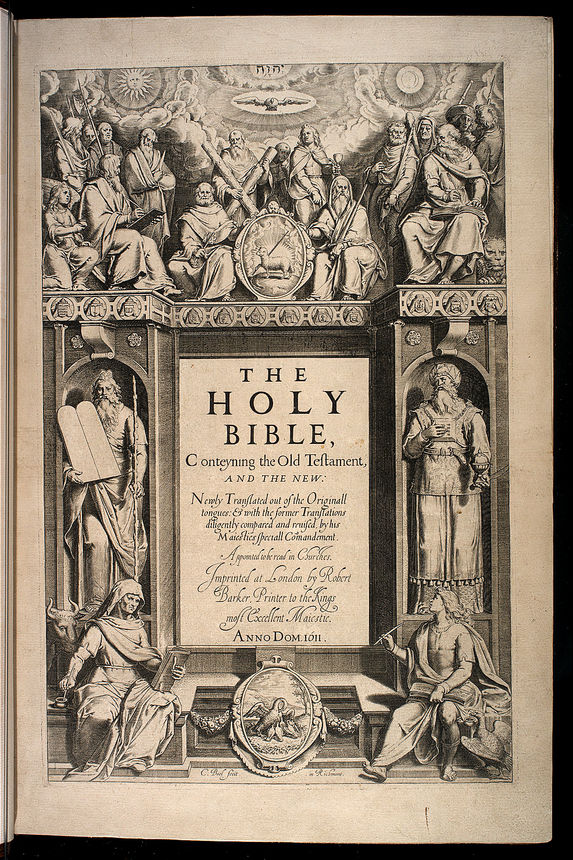

----The

preceding English Bibles in the 1500s laid the foundation for the new Anglican

English Bible in the early 1600s that would eventually become to the English

speaking Protestant world what the Latin Vulgate has been to Roman Catholicism.

From the middle 1600s until the late 1800s, "the Bible" meant the King

James Version to virtually all Protestants. And even to this day in small

numbers of ultra conservative groups of Protestants the KJV still remains

the only legitimate Bible. It has not only shaped Protestant understanding

about Christianity, but it has also shaped English speaking western culture

and literature profoundly. Consequently, we need to give more detailed

attention to it, than we did to the earlier English Bibles.

----The

preceding English Bibles in the 1500s laid the foundation for the new Anglican

English Bible in the early 1600s that would eventually become to the English

speaking Protestant world what the Latin Vulgate has been to Roman Catholicism.

From the middle 1600s until the late 1800s, "the Bible" meant the King

James Version to virtually all Protestants. And even to this day in small

numbers of ultra conservative groups of Protestants the KJV still remains

the only legitimate Bible. It has not only shaped Protestant understanding

about Christianity, but it has also shaped English speaking western culture

and literature profoundly. Consequently, we need to give more detailed

attention to it, than we did to the earlier English Bibles.

At the heart of the beginnings of the KJV is controversy. It is a reactionary translation. Among Puritans and a growing number of other Englanders was the huge popularity of the Geneva Bible. The leadership of the Church of England along with King James I became increasingly alarmed by this popularity. This wasn't due to the translation itself. Instead, the marginal notes that made the Geneva a study Bible were the sore spot. These notes advocated a Calvinist doctrinal viewpoint in conflict with the teachings of the Anglican Church. At certain points the note contained either direct or indirect criticism of the monarchy. Thus this translation was born out of the attempt to stamp out the influence of the Geneva Bible. The Geneva Bible had become the basis of severe criticism of the Bishops Bible that was the official English translation during this period. Thus the church leadership sought a means to revive an official English Bible like the Bishops Bible, but under a new name and with its own identity.

The "justifying rationale" was the perceived confusion coming from having many different English translations floating around the countryside. Jack P. Lewis describes the situation (p. 28):

Geneva Bibles were commonly used in homes, Bishops' Bibles in churches. Some Great Bibles were still around and perhaps even Tyndale and Coverdale Bibles could be found, though none of these three had been reprinted for a generation. Miles Smith in the "Translators to the Reader" of the KJV spoke of making one translation out of many good gones, to which men could not justly take exception. Though one can hardly envision King James doing a lasting service to Christendom, fate has its odd turns. John Reynolds' proposal of a new translation made at the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 caught King James' fancy, and he set in order the machinery to bring about the translation.

----The

launch pad for all this was the Hampton

Court Conference first called in 1604 by King

James I. The meeting was focused on reforming the Church of England.

Two groups were present. The bishops who represented the Church of England

officially, and a group of moderate Puritans who wanted to reform the British

church of its "popish" tendencies. The king moderated over the sessions.

One of the side products coming out of this was the organization of a translation

committee to produce a new English translation to help bring unity to Protestant

Christians in England and Scotland.

----The

launch pad for all this was the Hampton

Court Conference first called in 1604 by King

James I. The meeting was focused on reforming the Church of England.

Two groups were present. The bishops who represented the Church of England

officially, and a group of moderate Puritans who wanted to reform the British

church of its "popish" tendencies. The king moderated over the sessions.

One of the side products coming out of this was the organization of a translation

committee to produce a new English translation to help bring unity to Protestant

Christians in England and Scotland.

----Laurence

M. Vance provides a helpful

summation of this meeting at Hampton Court palace:

----Laurence

M. Vance provides a helpful

summation of this meeting at Hampton Court palace:

The conference at Hampton Court at which the Authorized Version was born was held within a year of James VI of Scotland becoming James I of England. And although a new version of the Bible was not on the agenda, God had his own agenda, and used the king and the conference participants alike to bring about his purposes.The translators were mandated to follow 15 guidelines in the production of the translation:

Soon after he acceded to the English throne, the new king was presented with the Millenary Petition, so called because "we, to the number of more than a thousand, of your Majesty’s subjects and ministers, all groaning as under a common burden of human rites and ceremonies, do with one joint consent humble ourselves at your Majesty’s feet to be eased and relieved in this behalf." This was the first, and most influential, of several petitions presented to the king by clergyman with Puritan leanings. The Puritans desired a more complete reformation in the Church of England. Extreme Puritans rejected Prelacy (church government by bishops) outright, as well as the Book of Common Prayer; moderate Puritans merely objected to certain ceremonies, such as wearing the surplice (a white ministerial vestment), and making the sign of the cross (traced on an infant’s forehead during baptism). Although the Act of Supremacy in 1534 had established King Henry VIII as "the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England," the Reformation in England progressed slower, lasted longer, and underwent more changes than any Continental reform movement. The reign of Elizabeth ended the external conflict with the Church of Rome, but this was followed by the internal conflict between Prelacy and Puritanism. It is to be remembered that there was no separation of church and state during this period in history – neither in Catholic nor Protestant countries.

The Millenary Petition begins with a preface reading: "The humble Petition of the Ministers of the Church of England desiring reformation of certain ceremonies and abuses of the Church." The moderate demands of the Puritans were subsumed under four heads: (1) In the Church Service, (2) Concerning Church ministers, (3) For Church livings and maintenance, (4) For Church Discipline. This was followed by the mention of a conference: "These, with such other abuses yet remaining, and practised in the Church of England, we are able to show not to be agreeable to the Scriptures, if it shall please your Highness farther to hear us, or more at large by writing to be informed, or by conference among the learned to be resolved." The petitioners sought "a due and godly reformation," and closed by addressing the king as did Mordecai to Esther: "Who knoweth whether you are come to the kingdom for such a time?"

Ever wanting to be tolerant and a reconciler of religious differences, King James set a date of November 1 for a conference in which the Puritans could state their case. This was scheduled months before he would even meet his first Parliament. There were English precedents, parallels, and sequences to the Hampton Court Conference, but none where the presiding moderator was a king, and not just any king, but a king who was keenly interested in theological and ecclesiastical matters, and quite at home in disputes of this nature. Regarding the Puritans, in a revised preface to the 1603 edition of his Basilikon Doron (The King’s Gift), printed in England within days of his accession to the throne, the king stated his unflinching opposition to the more radical Puritans. Thus, the Hampton Court Conference can be seen as primarily an attempt to settle the issue of Puritanism in the Church of England.

The Hampton Court Conference was soon postponed until after Christmas. In a royal proclamation dated October 24, 1603, the king mentioned "a meeting to be had before our Selfe and our Counsell, of divers of the Bishops and other learned men, the first day of the next month, by whose information and advice we might governe our proceeding therein, if we found cause of amendment." This was followed by three reasons for postponing the conference, chief of which was "by reason of the sicknesse reigning in many places of our Kingdome." Thus, because of an outbreak of the plague (which was killing thousands in London), the conference was postponed until January of the next year.

Beginning on a Saturday, the Hampton Court Conference was held on three days in January (14, 16, & 18) of 1604. It was held in a withdrawing room within the Privy Chamber. Here, a delegation of moderate Puritan divines met with the king and his bishops, deans (a church office below that of a bishop), and Privy Council (the king’s advisors). Several of the men who attended the Hampton Court Conference were later chosen to be translators of the proposed new Bible. The participants on the first day were limited to the king, the bishops, five deans, and the Privy Council. Day two saw the Puritan representatives, two bishops, and the deans meet with the king and his Council. The third day was a plenary session.

There survives several accounts of the Hampton Court Conference. The official account, which is also by far the longest, was commissioned by Bishop Bancroft of London a few weeks after the conference closed. It was written by William Barlow, who attended the conference in his capacity as the Dean of Chester, and was published in August of 1604 as The Summe and Substance of the Conference, which, it pleased his Excellent Maiestie to have with the Lords, Bishops, and other of his Clergie, (at which the most of the Lordes of the Councell were present) in his Maiesties Privy-Chamber, at Hampton Court. January 14, 1603. The other accounts of the conference include letters about the conference written soon after its close by four participants, including the king himself, an anonymous account supposedly favoring the bishops, and four anonymous accounts supposedly favoring the Puritans.

Representing the Puritans at the Hampton Court Conference were Dr. John Rainolds (1549–1607), Laurence Chaderton (1537–1640), Dr. Thomas Sparke (1548–1616), and John Knewstubs (1544–1624). Rainolds was president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. It was he who put forth the suggestion at the conference that a new translation of the Bible be undertaken. He was also one of the translators, serving on the company that translated the Prophets. Rainolds, of whom it was said: "He alone was a well-furnished library, full of all faculties, of all studies, of all learning; the memory, the reading of that man were near to a miracle," acted as the "foreman" for the Puritan group. Chaderton was the master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and a prebendary (a receiver of cathedral revenues [a "prebend"]) of Lincoln Cathedral. He was a noted Latin, Greek, and Hebrew scholar, and also served as one of the translators of the future Bible. Chaderton preached to large crowds at Cambridge for nearly fifty years. Sparke was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he earned four degrees. He had earlier represented the Puritans in a conference held at Lambeth Palace in December 1584. Knewstubs was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge. He was an ardent controversialist. At the Hampton Court Conference, he took special exception to the use of the sign of the cross in baptism and the wearing of the surplice, equating it with garments worn by the priests of Isis, for which he was rebuked by the king.

There were nine bishops in attendance at the Hampton Court Conference: John Whitgift (1530–1604), Richard Bancroft (1544–1610), Thomas Bilson (1547–1616), Thomas Dove (1555–1630), Anthony Watson (d. 1605), Gervase Babington (1550–1610), Henry Robinson (1553–1616), Anthony Rudd (1549–1615), and Tobie Matthew (1546–1628).

Whitgift was the aging Archbishop of Canterbury. He had drawn up the Calvinistic Lambeth Articles in 1595, which articles were to be mentioned at the Hampton Court Conference. Bancroft was the bishop of London and successor of Whitgift as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Bilson was the bishop of Winchester, Dove of Peterborough, Watson of Chichester, Babington of Worcester, Robinson of Carlisle, Rudd of St. David’s, and Matthew of Durham. Bancroft and Bilson each had a role in the production of the King James Bible – Bancroft as a translator, and Bilson, with Miles Smith (d. 1624), as a final editor. It is Bilson who is thought to have written the dedication to King James that appeared at the front of the new version that came to be called after his name. This "Epistle Dedicatory" is sometimes still printed at the front of some editions of the Authorized Version.

The bishops of the Church of England were joined by nine deans. William Barlow (d. 1613), Lancelot Andrewes (1555–1626), John Overall (1560–1619), James Montague (1568–1618), George Abbot (1562–1633), Thomas Ravis (1560–1609), Thomas Edes (1555–1604), Giles Thomson (1553–1612), and John Gordon (1544–1619).