The History of the Bible

--Lecture

Notes for Topic 3.0-

--Lecture

Notes for Topic 3.0-

Establishing

a Christian Bible: 100 AD to the Protestant Reformation

Last revised: 10/01/06

Explanation:

Contained below

is a manuscript summarizing the class lecture(s) covering the above specified

range of topics covered in the study. To display any Hebrew or Greek

text contained in this page download and install the free BSTHebrew and

BSTGreek

from Bible Study Tools.

Created

by  a division of

a division of  All rights reserved©

All rights reserved©

|

|

|

What do we need

to learn this week?

After examining how both testaments

of the Christian Bible came into being, we need now to take a look

at how they came together as a Bible comprised of the Old Testament and

the New Testament. That history should give attention first to how

copies of sacred documents were made. This will be foundational to

these documents being distributed and thus sought to gain credibility in

the eyes of various ancient Christian communities. The result of this copying

process was to produce thousands of manuscripts that were distributed either

as individual documents or mostly as a collection of documents. The hand

copying process had numerous weaknesses built into it. The result was to

produce manuscripts that contained large numbers of variations in wording

in the texts.

The immediate question that comes is

"Where does the content of our English Bible come

from?" Since the beginning of the modern era of the printing press,

those who print a Greek New Testament and a Hebrew Old Testament are forced

by necessity to make decisions about the exact wording of a biblical language

text. How are such decisions made? On

what basis, since the copied manuscripts differ so much in their wording?

The answer to these questions lies in a brief overview of a technical process

of analyzing the now existing manuscripts of the biblical texts. The goal

is to seek the most accurate wording possible. The standard for measuring

accuracy is the exact wording of each document when it was first written.

But why not just go back to the original documents

themselves? Unfortunately, these documents no longer exist. And

further complicating the process is that for the New Testament, existing

manuscripts, that cover the full content of the New Testament, reach back

no earlier than three hundred years after the original writing of each

document. The situation is more challenging for the Hebrew test of the

Old Testament. This process of analysis of available manuscripts is a highly

technical discipline called

Textual Criticism. We will

take a quick look at it, both in its New Testament application, and also

in its very different Old Testament application.

Finally, we will give consideration

to the central role that the Latin Vulgate has played

in Christian history. By the fifth century it had become the

Bible for western Christianity. And it remained so for all Christians in

the west until the Protestant Reformation. For Roman Catholics it still

remains the Bible. Additionally, it has impacted the English Bible in many,

many ways from the very beginning, and remains an influence on the English

Bible used by most Protestants today. Modern English Roman Catholic translations

must pay close attention to the Vulgate, if these are to gain the approval

of the Vatican.

3.1

Copying

the Bible: How were copies of the Bible

made before the printing press?

In the ancient

world, no typewriters or computers existed. So

how did people put their ideas in written expression?

The answer: very laboriously, using very primitive writing tools. This

tended to push writing toward the experts who were especially trained for

this. By the beginning of the Christian era, most writing outside of very

short personal letters -- less than one page -- was done by professional

scribes.

3.1.1

How did people write in the ancient world?

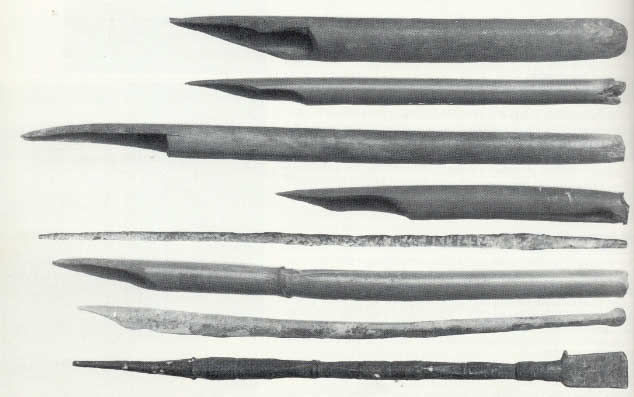

In the world at the beginning of the

Christian era a variety of writing materials were used. Each tended to

have specific purposes and situations. The graphics below illustrate the

variety of materials and instruments used in writing.

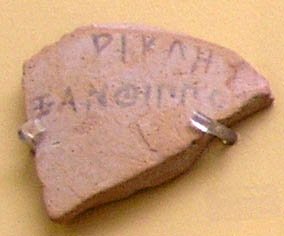

Of the five types of writing materials

illustrated above, the wax tablet was the main writing material for school

boys, although it was used for other things. A fine layer of wax was spread

over a flat piece of wood. The wax could be heated to erase the writing

that had been placed on it using a stylus while the wax was warm. Ostraca

was pottery with inscriptions etc. on it. Most of what we have available

today are broken pieces of pottery. "Paper" was not produced until after

the 8th century AD, and does not figure in prominently with the copying

of the Bible until the middle ages. Papyrus was the most common writing

material in the ancient world, and was widely used. Parchment -- Vellum

-- was tanned leather and was widely used in copying the Bible from the

fourth through the fourteenth centuries. The writing instruments ranged

from hollowed out reeds to bone or wooden styla.

3.1.2

Who did the copying of the documents of the New Testament and how?

A dramatic dividing line in the copying

process exists. Up to the fourth century, those who copied the texts of

the New Testament were not professional scribes who did this for a living.

Most were what we would call "laymen." They spent enormous amounts of time

making copies as a part of their Christian faith, and without pay for doing

it. But with the Edict

of Milan in 313 AD, the Roman emperor Constantine

declared Christianity to be the official religion of the Roman Empire,

making it a religio licita. Although other religions were tolerated,

Christianity increasingly became the dominant religion of the empire. One

of the byproducts of that action was to make the enormous financial support

of the Roman government available to Christian churches. This shifted the

copying of manuscripts of the Bible from volunteer scribes to professionally

trained scribes. The quality and way of copying noticeably changed as evidenced

by the use of much more expensive materials and a much more decorative

style of manuscript production.

The methods of copying usually followed

one of two patterns. First, a scribe would

have a copy of the biblical text (= exemplar) in front of him. Using the

appropriate writing materials (papyrus until the fourth century

AD, and mostly parchment after that), he would visually copy by

hand each word onto the new manuscript. The result of such a long, laborious

effort over several months would be one more copy of the New Testament.

Second, a group of scribes would gather each

with appropriate writing materials. The number would vary according to

the circumstance. Another scribe would orally read aloud the exemplar text

to the group of copyists, who would carefully write down what they heard

being read. The result of such a long, grueling period of copying would

be several new Biblesm depending on the number of the group of scribes.

Both methods took months and months of hard work to produce each new copy.

But the second method was much more efficient in that multiple copies resulted

from the process. The advantage of the first method was that fewer mistakes

would be made in the copying process. From every indication, the second,

group method was the most common way of copying the New Testament.

Such a process is naturally going to

produce numerous variations of wording in the copied manuscripts. Rich

Elliott has a very helpful summary of the core challenges to the scholar

analyzing these manuscripts in order to determine the text of the Greek

New Testament:

Chances

are that you've played the game "Telephone" some time in your life. "Telephone"

is the game in which a group of people gather around in a circle. One person

thinks up a message, and whispers it to the next person, who whispers it

to the next person, and so on around the circle, until you reach the end

and the final person repeats the message aloud. The first person then states

the original message.

The

two sentences often cannot be recognized as related.

Even

if you haven't played "Telephone," you must have read a book or a magazine

which was filled with typographical errors. And that's in a case where

the typesetter has the author's original manuscript before him, and professional

proofreaders were engaged to correct errors.

Now

imagine what happens when a document is copied, by hand, tens of thousands

of times, long after the original manuscript has been destroyed. Imagine

it being copied by barely literate scribes standing (not sitting, standing)

at cold desks in bad light for hours on end, trying to read some other

scribe's barely legible handwriting.

Imagine

trying to do that when the words are written in all upper-case letters,

with no spaces between words, and you're writing on poor quality paper

with a scratchy reed pen using ink you made yourself.

Because

that's what happened with all ancient books, and with the New Testament

in particular. Not all scribes were as bad as the secretary Chaucer poked

such fun at in the quote above, but none were perfect -- and few had the

New Testament authors looking over their shoulders to make corrections.

After

a few centuries of that, it's easy to imagine that the text of the New

Testament would no longer bear any relationship to the original. Human

beings just aren't equipped to be exact copyists. And the more human beings

involved in the process, the worse the situation becomes.

Fortunately,

the situation is not as grim as the above picture would suggest. Despite

all those incompetent scribes making all those incompetent copies, the

text of the New Testament is in relatively good shape. The fact that copies

were being made constantly, by intent scribes under the supervision of

careful proofreaders, meant that the text stayed fairly fixed. It is estimated

that seven-eighths of the New Testament text is certain -- all the major

manuscripts agree, and scholars are satisfied that their agreement is correct.

Most of the rest is tolerably certain -- we probably know the original

reading, and even if we aren't sure, the variation does not significantly

affect the sense of the passage. For a work so old, and existing in so

many copies, this fact is at once amazing and comforting.

Still,

there are variations in the manuscripts of the New Testament, and some

of them are important. It is rare for such variants to affect a fundamental

Christian doctrine, but they certainly can affect the course of our theological

arguments. And in any case, we would like the most accurate text of the

New Testament possible.

That

is the purpose of textual criticism: Working with the materials available,

to reconstruct the original text of an ancient document with as much accuracy

as possible. It's not always an easy job, and scholars do sometimes disagree.

But we will try to outline some of the methods of New Testament textual

criticism in this article, so that you too can understand the differences

between Bibles, and all those odd little footnotes that read something

like "Other ancient authorities read...."

For a very helpful and not overly technical

discussion of the types of variations that show up as a result of this

copying process see Tony Sied's, "Manuscript

Transmission," in Interpreting

Ancient Manuscripts web site. Numerous illustrations are presented

as well.

3.1.3

Who did the copying of the documents of the Old Testament and how?

When one comes to the copying of the

Old Testament documents, the situation and the dynamics are very different

from that with the New Testament.

In Judaism

the biblical texts in Hebrew were being copied at the beginning of the

Christian era to some extent. The preference for oral transmission was

still dominant. But more importantly, they were gradually being incorporated

into larger writings that by the fourth century AD would become known as

the Talmud. This is defined

as:

The

Talmud is a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics,

customs and history. The Talmud has two components: the Mishnah, which

is the first written compendium of Judaism's Oral Law; and the Gemara,

a discussion of the Mishnah and related Tannaitic writings that often ventures

onto other subjects and expounds broadly on the Tanakh. The terms Talmud

and Gemara are often used interchangeably. The Gemara is the basis for

all codes of rabbinic law and is much quoted in other rabbinic literature.

The whole Talmud is traditionally also referred to as Shas (a Hebrew abbreviation

of shishah sedarim, the "six orders" of the Mishnah).

The written Hebrew texts of the Old Testaments

will come together in an organized and semi-official manner through the

work of Jewish rabbis known as the Masoretes

who worked between the seventh and eleventh centuries AD. The standardized

Hebrew text they produced is called the Masoretic

Text of the Old Testament. This Hebrew text has become the foundation

for all printed Hebrew texts used by Jewish and Protestant scholars in

the modern era. Increasingly, Roman Catholic scholars are adopting it as

well, especially after Vatican Council Two in the early 1960s.

In Christianity,

however, the Old Testament pretty much meant the Septuagint

until Jerome's Vulgate at the end of the fourth century. So most of the

copying of the Old Testament during this period related to copying the

Greek translation of the Old Testament, as well as the use of it for translation

into Latin and other languages in the Eastern Mediterranean world. Although

not a lot is known about the copying process at this early period, one

would assume that the methods etc. of copying were similar to those used

with the New Testament documents also in Greek.

When one comes to the rise of the influence

of the Latin Vulgate in western Christianity from the fifth century onward,

the process of copying either the Greek Old Testament or the Greek and/or

Hebrew Old Testament diminishes dramatically because the concern now focuses

on transmission of the Vulgate. It has become the Bible of Latin speaking

Christianity universally. Even the study of these original biblical language

texts drops significantly with the passing of time. So much so that only

the monastics tucked away in isolated monasteries become the individuals

who can read and study these texts.

3.2

Analyzing

all these copies: How do we get back

to the words originally written in these documents?

3.2.1

Some history of the process called Textual

Criticism

The beginnings of Textual Criticism

as a formal discipline lie outside the study of the Bible. On the European

continent the study of folk literature, in England the study of Shakespeare's

writings -- these and others areas became the foundation for textual criticism

in the modern era. Analysis of different manuscripts of the writings of

individuals, to be sure, had been practiced for a long time, many centuries

before the modern era. But never with the carefully developed procedures

etc. for analysis as is true in the modern period. The history of the transmission

of the Vulgate clearly illustrates this.

The dramatic expansion of this discipline

is connected to two dynamics. First, the invention

of the printing press created impetus for producing a printed Greek text

of the New Testament in the early 1500s. This meant that some hand copied

manuscript or collection of manuscripts of the Greek New Testament had

to be examined in order to determine the wording of the Greek text for

printing purposes. In the early 1500s, many European scholars were feverishly

working to be the first one to publish a Greek New Testament. The one who

succeeded was the Dutch scholar Erasmus,

who published the first Greek New Testament in 1516. This volume and subsequent

editions came to be called the Textus

Receptus.

While

in England Erasmus began the systematic examination of manuscripts of the

New Testament to prepare for a new edition and Latin translation. This

edition was published by Froben of Basel in 1516 and was the basis of most

of the scientific study of the Bible during the Reformation period (see

Bible Text, II., 2, § 1). He published a critical edition of the Greek

New Testament in 1516 - Novum Instrumentum omne, diligenter ab Erasmo Rot.

Recognitum et Emendatum. This edition included a Latin translation and

annotations. It used recently rediscovered additional manuscripts. In the

second edition the more familiar term Testamentum was used instead of Instrumentum.

But it was the third edition that was used by the translators of the King

James Version of the Bible. The text later became known as the Textus Receptus.

The first and second editions' text did not include the passage (1 John

5:7–8) that has come to be known as the Comma Johanneum. This appears to

be a basis of the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds, but it is, most likely,

a forgery. The Roman Catholic Church decreed that the Comma Johanneum was

open to dispute (June 2, 1927), and it is rarely, if ever, included in

modern translations. Erasmus published three other editions - in 1522,

1527 and 1535. Erasmus dedicated his work to Pope Leo X as a patron of

learning, and he regarded this work as his chief service to the cause of

Christianity. Immediately afterwards he began the publication of his Paraphrases

of the New Testament, a popular presentation of the contents of the several

books. These, like all of his writings, were published in Latin, but were

quickly translated into other languages, with his encouragement. [Wikipedia,

"Erasmus"]

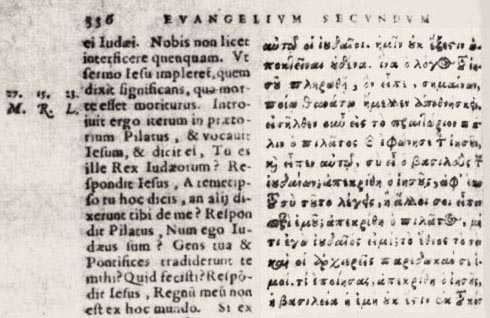

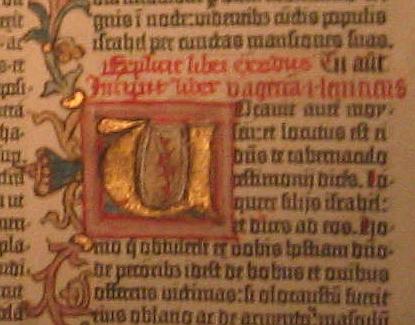

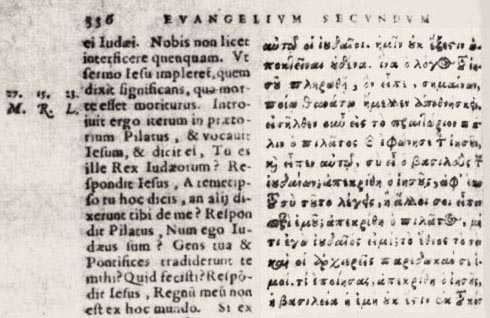

Copy of Erasmus' text with the Vulgate

in the left column and his Greek text in the right

column. Erasmus represents the beginning

of the so-called "Textus Receptus," the received text. |

|

This printed Greek text and subsequent

editions became the basis for translating the New Testament in the various

European languages for the next two hundred years. This to the slim extent

that those translations consulted an original language text, rather than

depending exclusively on the Vulgate as the foundational text for translation.

Second,

the emergence of biblical

archaeology in the eighteen hundreds gradually began uncovering more

and more manuscript fragments and occasionally virtually complete texts

of the New Testament. These copies went further back in time than the few

manuscripts that Erasmus had used to produce his printed Greek text. As

more and more texts of the Bible were discovered, biblical scholars began

noticing increasing variations of wording from the text of the Textus Receptus.

The discovery of Codex

Alexandrinus in the early 1800s became a catalyst for much of this,

since it was a fifth century copy of virtually the entire text of the New

Testament. The manuscripts used in the Textus Receptus only went back to

the middle ages. So here was a Greek text reaching back centuries farther

than anything connected to the Textus Receptus. And, most importantly,

it contained numerous differences in wording from that of the Textus Receptus.

Increasingly, biblical scholars became alarmed about the trust worthiness

of the Greek text that lay underneath the translations in the Textus Receptus.

Over the past 150 years, we have moved

from having access to barely a dozen very late and very inferior Greek

manuscripts of the New Testament to over 5,300 manuscripts. Many of these

manuscripts move to within four centuries of the original writings of the

documents of the New Testaments, and, in a few instances, manuscript fragments

move to with a century of the compositional date. Many of these manuscripts

are very high quality, as well as being dated very early. Add to this,

the discovery of ancient

translations in Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Ethiopic, Georgian

and other languages. This pushes the available texts of the New Testament

in translation form back to within a few centuries of the original writing

dates. Complementing this still growing mountain of evidence are the lectionaries

written in Greek that quote large portions of the New Testament. Additionally

are the Church

Fathers, especially those who wrote in Greek, who also quote from the

Greek text of the New Testament being used in their writing.

Unlike the challenge with the ancient

Hebrew and Greek texts of the Old Testament where very few manuscripts

go back to within a few centuries of the original date of writing, scholars

in New Testament Textual Criticism face the huge challenge of sifting through

literally thousands and thousands of ancient manuscripts as they attempt

to get at the most likely reading of the original writing of the New Testament

documents. A systematic method of evaluating all this evidence becomes

essential.

3.2.2

A glance at how the experts do it

The essence of this procedure is first

to compare external evidence, that is, available manuscripts for the scripture

text. Then internal evidence, i.e., patterns of scribal writing showing

up inside the Greek text, is analyzed. When a variety of alternative "readings"

of a word, phrase etc. shows up in a scripture passage, then both the external

and internal evidence are compared in order to draw a conclusion regarding

"the most likely original reading" of the Greek text.

The possible readings are evaluated

externally by (1) how early the manuscript

support is for each reading, by (2) widely geographical regions the readings

existed in, and by (3) which text family or tradition they belong to. The

earlier a certain reading is, the more widely distributed it is geographically,

and the more text types it can be found in, the stronger is the evidence

supporting a certain reading of the text. Internally,

two areas of evaluation are use: (1) what the scribes probably did when

copying the New Testament (Transcriptional Probabilities), and (2) what

the author most likely wrote himself (Intrinsic Probabilities).

For a more detailed explanation see

my my "EVALUATION OF VARIOUS READINGS ACCORDING TO THE THEORY OF RATIONAL

ECLECTICISM" in Supplementary

Helps in Greek 202

at Cranfordville.com in the Academic Section (in pdf

file format). It is summarized by the following chart:

EVALUATION OF EXTERNAL EVIDENCE

1. Date.

2. Geographical Distribution.

3. Textual Relationships.

Summary of the External Evidence |

EVALUATION OF THE INTERNAL EVIDENCE

1. Transcriptional Probabilities,

i.e. what scribes likely did when copying the N.T.

(1)

Shorter/Longer Reading.

(2)

Reading Different from Parallel.

(3)

More Difficult Reading.

(4)

Reading Which Best Explains Origin of Other(s).

2. Intrinsic Probabilities,

i.e. what the author himself likely wrote.

Summary of Internal Evidence |

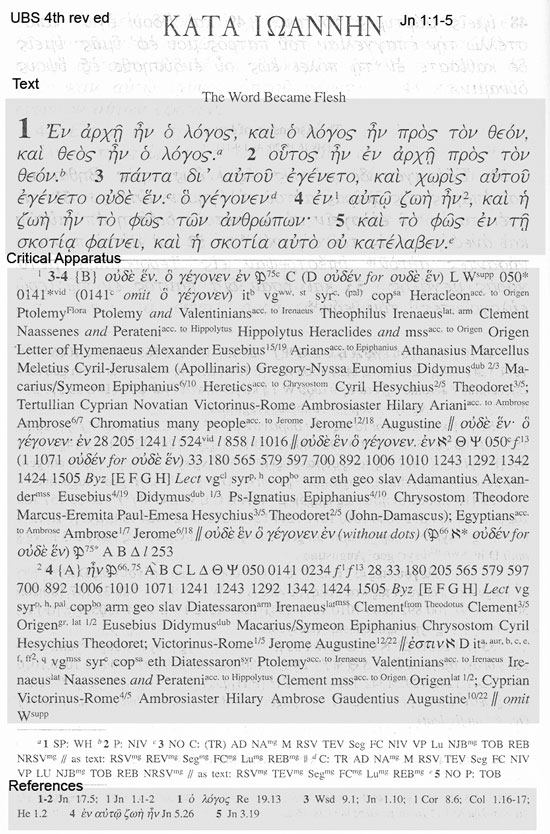

In the UBS 4th revised edition the critical

apparatus applies this procedure and then rates the reading used for the

text with a grading system. An "A" represents the highest level of

confidence and a "D" the lowest level of confidence. The descending scale

of certainty reflects a balancing of weight among the possible readings

so that one cannot be as certain about which one of the readings was the

original. The alternative readings, called variant readings, have less

evidence supporting them.

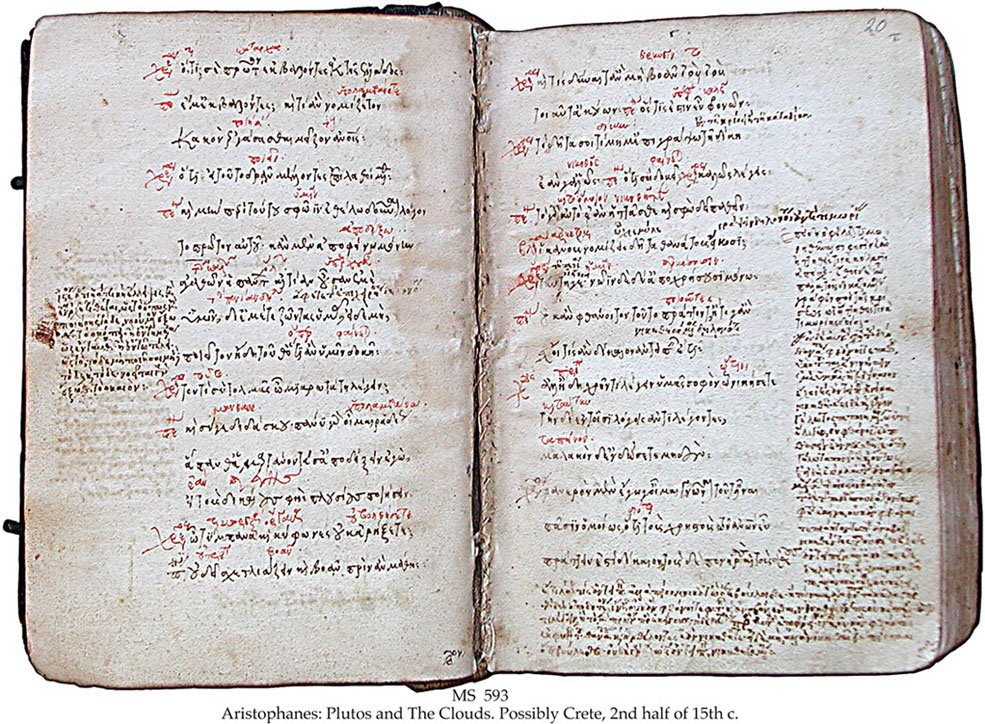

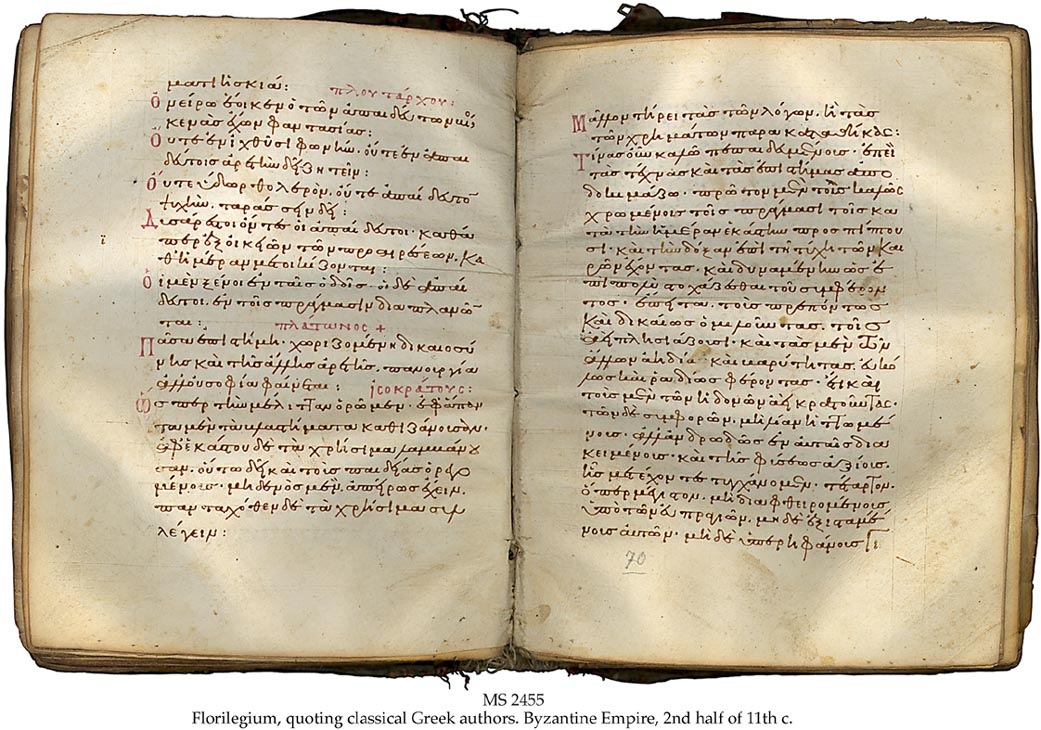

Some representative types of ancient

copies of the Greek New Testament are:

|

|

| This manuscript is Papyrus

66 that dates from about 200 AD. The all caps Greek writing was done

on papyrus, the most common writing material of

that time. P66 contains most of the Gospel of John. |

This manuscript is Uncial Sinaiticus

(01) that dates during the fourth century AD. It was written on parchment,

the material that became common after Christianity became the official

religion of the Roman Empire. It contains virtually all of the New Testament |

|

| This is a minusucle manuscript and

illustrates a later "script" style of writing that developed toward the

end of the ancient period. It became the dominant way of writing Greek

and thus most all the later manuscripts of the Greek New Testament are

written in this style of writing. Previously Greek had been "printed" using

only capital letters, as can be seen from the two above manuscripts written

on papyrus and parchment. |

3.2.3

The

results of their work: printed Greek and Hebrew texts

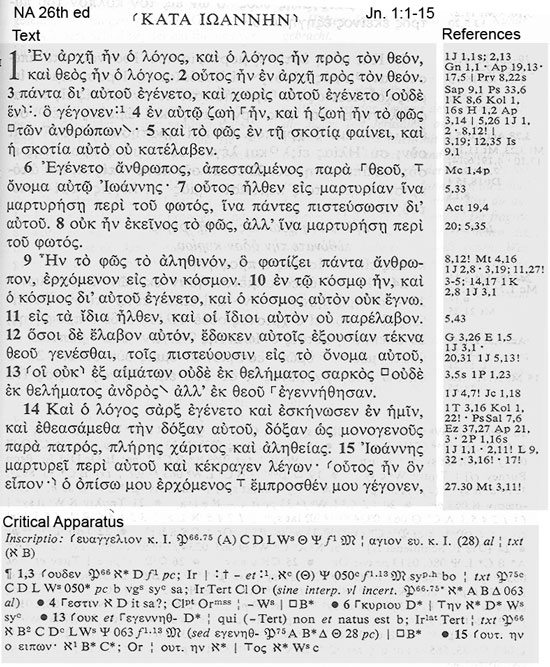

For students of the Greek New Testament,

the two most commonly used printed Greek texts of the New Testament are

The United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament fourth revised edition

and the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece 27th edition. Both provide

a "critical apparatus" at the bottom of each page that lists the major

manuscripts supporting the possible alternative readings. The Logos

Bible Software site has a helpful explanation of these features for

both the Greek New Testament and the Hebrew Old Testament. For the instructions

and examples that I use with the Greek 202 students when they begin practicing

the procedure see my "EVALUATION OF VARIOUS READINGS ACCORDING TO THE THEORY

OF RATIONAL ECLECTICISM" in Supplementary

Helps in Greek 202

at Cranfordville.com in the Academic Section (in pdf

file format). For another very helpful summation of the history of

Text Criticism, see Ronald J. Gordan's Comparing

Translations.

From these two illustrations below of

the UBS text and then the Nestle-Aland Greek texts you can see something

of what they look like. I have indicated by label and highlighting the

Greek text, then the Critical Apparatus and also the cross references to

other verses in each one.

For the really "eager beavers" in the

group Prof. Sied has created an "exercise in textual criticism" using the

English language set up to simulate what one would find in the Greek New

Testament. It's fun to go through, and also provides a "hands on" feel

for what this procedure is all about. Click on the  icon in Sied's Interpreting

Ancient Manuscripts web site. Also, professor Elliott has a very helpful

list of examples

that one can work through in order to gain a feel for doing this kind of

work.

icon in Sied's Interpreting

Ancient Manuscripts web site. Also, professor Elliott has a very helpful

list of examples

that one can work through in order to gain a feel for doing this kind of

work.

3.2.4

How

does this work impact your study of the Bible?

At least two areas of consequence will

be seen for the reader of the English Bible. First,

Bible translation means that the translators have to have a Greek New Testament

in hand as the starting point for translation. You can't "translate" without

a source text to translate. In today's world of Bible translation,

this means the use of the most reliable Greek text possible, since the

goal is to translate into English the most likely wording of the original

text of the New Testament documents. Textual criticism is the procedure

for establishing that Greek text as far as is humanly possible.

The consequence of this will also mean

that sometimes when different English translations have significantly different

wording in passages, they are working from different Greek texts of the

New Testament. This will particularly be true when comparing the King James

Version to an English translation produced in the second half of the twentieth

century onward. Also the New King James Version and the 1979 Revised King

James Version will use a sometimes radically different Greek text than

the other English translations.

Another impact

will be seen in the more recent English translations in their footnote

system. For example, the New

Revised Standard Version has a footnote in the middle of 1:18. The

printed translation reads: "No one has ever seen

God. It is God the only Son,e/F5

who is close to the Father's heart, who has made him known." Footnote

e/F5

then reads: "Other ancient authorities read It

is an only Son, God, or It

is the only Son." What

this difference in translation means is that the manuscripts of this verse

in John differ on their wording of the text. The weight of evidence is

not decisive one direction or the other. The translators of the NRSV concluded

on one reading of the Greek text and then gave their English translation

based on that understanding. But they are being honest with us readers

by inserting a footnote to suggest how the English translation would differ

if the one of the two other possible readings of the Greek text were adopted.

3.3

The

importance of the Latin Vulgate: What

Bible have Christians mostly used over the centuries?

One of the first languages that the

New Testament documents were translated into was Latin.

This language was spoken first on the Italian peninsula and then with the

establishment of the Roman Empire just before the beginning of the Christian

era it became the official language of the Roman government all over the

Mediterranean world.

3.3.1

Establishing the Vulgate

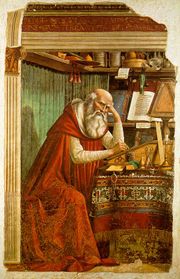

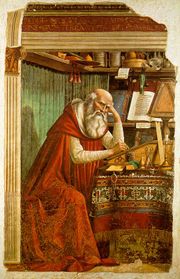

---There

were many efforts to translate the Greek original documents into “old Latin”

but from

the

available Latin translations it is clear that the majority of these

were

of very poor quality. The situation deteriorated to the point that

“in

382 that Pope Damascus (366-384) called upon Jerome (Sophronius Eusebius

Hieronymus) to remedy the situation. Jerome

was the greatest scholar of his generation, and the Pope asked him to make

an official Latin version -- both to remedy the poor quality of the existing

translations and to give one standard reference for future copies. Damasus

also called upon Jerome to use the best possible Greek texts -- even while

giving him the contradictory command to stay as close to the existing versions

as possible” (“Vulgate,” Encyclopedia

of Textual Criticism).

---There

were many efforts to translate the Greek original documents into “old Latin”

but from

the

available Latin translations it is clear that the majority of these

were

of very poor quality. The situation deteriorated to the point that

“in

382 that Pope Damascus (366-384) called upon Jerome (Sophronius Eusebius

Hieronymus) to remedy the situation. Jerome

was the greatest scholar of his generation, and the Pope asked him to make

an official Latin version -- both to remedy the poor quality of the existing

translations and to give one standard reference for future copies. Damasus

also called upon Jerome to use the best possible Greek texts -- even while

giving him the contradictory command to stay as close to the existing versions

as possible” (“Vulgate,” Encyclopedia

of Textual Criticism).

It would take him until well into the

400s to complete this project since he did a substantial amount of comparing

available Greek and Hebrew manuscripts of the Old Testament and Greek manuscripts

of the New Testament. The mandate was to use the best manuscripts but to

stay close to the existing Latin translations. This necessitated careful

translation work in trying to strike a balance. Jerome faced what modern

Bible translators have often faced. In the beginning, his work was soundly

criticized because it departed in places from accepted wording found in

both some popular old Latin versions and, even more, from the very popular

Greek Septuagint. But Jerome based his deviations on solid analysis of

available manuscripts in both Latin and Greek. Gradually, those criticisms

faded.

The copying of Jerome's Vulgate took

place from the 400s to the 1500s and resulted in lines or families of texts

in the many generations of copies. Unfortunately, the quality of the copying

process tended to become increasingly inferior and thus the quality of

the Vulgate text deteriorated substantially over time. Numerous variations

of readings of the Vulgate surfaced, so that the situation by the 1500s

became pretty much the same as that which had prompted the creation of

the Vulgate in the late 300s with the Old Latin texts of the Bible.

The Encyclopedia

of Textual Criticism offers a summary of the various "families" of

Vulgate texts that developed:

With that firmly in mind, let us turn to the various types of Vulgate text

which evolved over the centuries. As with the Greek manuscripts, the various

parts of Christendom developed their own "local" text.

The best "local" text is considered to be the Italian

type, as represented e.g. by am and ful. This

text also endured for a long time in England (indeed, Wordsworth and White

call this group "Northumbrian"). It has formed the basis for most recent

Vulgate revisions.

Believed to be as old as the Italian, but less reputable, is the Spanish

text-type, represented by cav and tol. Jerome

himself is said to have supervised the work of the first Spanish scribes

to copy the Vulgate (398), but by the time of our earliest manuscripts

the type had developed many peculiarities (some of them perhaps under the

influence of the Priscillians, who for instance produced the "three heavenly

witnesses" text of 1 John 5:7-8).

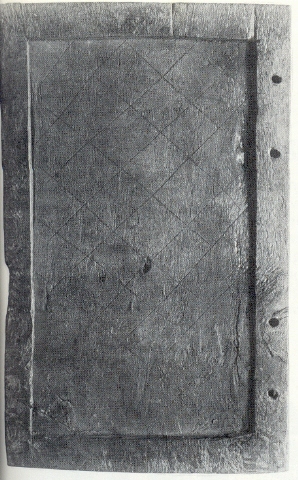

The Irish text

is marked by beautiful manuscripts (the Book of Kells and the Lichfield

Gospels, both beautiful illuminated manuscripts, are of this type, and

even unilliminated manuscripts such as the Rushworth Gospels and the Book

of Armagh are beautiful examples of calligraphy). Sadly, these manuscripts

are often marred by conflations and inversions of word order. Some of the

manuscripts are thought to have been corrected from the Greek -- though

the number of Greek scholars in the Celtic church must have been few indeed.

Lemuel J. Hopkins-James, editor of The Celtic Gospels (essentially a critical

edition of codex Lichfeldensis) offers another theory: that this sort of

text (which he calls "Celtic" rather than Irish) is descended not from

a pure Vulgate manuscript but from an Old Latin source corrected against

a Vulgate. (It should be noted, however, that Hopkins-James uses statistical

comparisons to support this result, and the best word I can think of for

his method is "ludicrous.")

The "French" text

has been described as a mixture of Spanish and Irish readings. The text

of Gaul (France) has been called "unquestionably"

the worst of the local texts.

The wide variety of Vulgate readings in Charlemagne's time caused that

monarch to order Alcuin to attempt to create a uniform version (the exact

date is unknown, but he was working on it in 800). Unfortunately, Alcuin

had no critical sense, and the result was not a particularly good text.

Still, his revision was issued in the form of many beautiful codices.

Another scholar who tried to improve the Vulgate was Theodulf, who also

undertook his task near the beginning of the ninth century. Some have accused

Theodulf of contaminating the French Vulgate with Spanish readings, but

it appears that Theodulf really was a better scholar than Alcuin, and produced

a better edition than Alcuin's which also included information about the

sources of variant readings. Unfortunately, such a revision is hard to

copy, and it seems to have degraded and disappeared quickly (though manuscripts

such as theo, which are effectively contemporary with the edition, preserve

it fairly well).

Other revisions were undertaken in the following centuries, but they really

accomplished little; even if someone took notice of the revisors' efforts,

the results were not particularly good. When it finally came time to produce

an official Vulgate (which the Council of Trent declared an urgent need),

the number of texts in circulation was high, but few were of any quality.

The result was that the "official" Vulgate editions (the Sixtine

of 1590, and its replacement the Clementine

of 1592) were very bad. Although good manuscripts

such as Amiatinus were consulted, they made little impression on the editors.

The Clementine edition shows an amazing ability to combine all the faults

of the earlier texts. Unfortunately, it was to be nearly three centuries

before John Wordsworth undertook a truly critical edition of the Vulgate,

and another century after that before the Catholic Church finally accepted

the need for revised texts.

Despite all that has been said, the Vulgate remains an important version

for criticism, and both its "true" text and the variants can help us understand

the history of the text. We need merely keep in mind the personalities

of our witnesses. The table below is intended to help with that task as

much as possible.

At the Council

of Trent in 1545, the Roman Catholic Church declared the Vulgate to

be the official Bible of the church. This was in reaction to Protestants

placing increasing stress on the original language texts of the Bible.

In 1590 the Catholic Church published the Sixtine Vulgate, but upon realizing

the sorry manuscript basis it quickly released a revision in 1592 known

as Clementine

Vulgate. Unfortunately, the quality of the manuscript basis for this

revision wasn't very much better than for the Sixtine Vulgate. John Wadsworth,

Bishop of Salisbury (1885-1911), and H.J. White, at the end of the 1800s

produced a revision in 1889. This edition had better manuscript evaluation

underneath it. The Nova Vulgata released initially in 1979 for the entire

Bible is the current official version of the Vulgate for the Roman

Catholic Church. This current edition is the product of a commission appointed

in 1965 by Pope John Paul VI at the end of the Second Vatican Council.

This edition is based on careful analysis of the many manuscripts housed

in Rome at the Vatican library. Below is a copy of the Nova Vulgata translation

of John 1:1-18. I've included in the right hand column the New Revised

Standard Version translation of the same scripture passage in contemporary

English.

| The

Latin Vulgate |

NRSV |

1 in principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum

2 hoc erat in principio apud Deum 3 omnia per ipsum facta sunt et sine

ipso factum est nihil quod factum est 4 in ipso vita erat et vita erat

lux hominum 5 et lux in tenebris lucet et tenebrae eam non conprehenderunt

6 fuit homo missus a Deo cui nomen erat Iohannes 7 hic venit in testimonium

ut testimonium perhiberet de lumine ut omnes crederent per illum 8 non

erat ille lux sed ut testimonium perhiberet de lumine 9 erat lux vera quae

inluminat omnem hominem venientem in mundum 10 in mundo erat et mundus

per ipsum factus est et mundus eum non cognovit 11 in propria venit et

sui eum non receperunt 12 quotquot autem receperunt eum dedit eis potestatem

filios Dei fieri his qui credunt in nomine eius 13 qui non ex sanguinibus

neque ex voluntate carnis neque ex voluntate viri sed ex Deo nati sunt

14 et Verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis et vidimus gloriam eius

gloriam quasi unigeniti a Patre plenum gratiae et veritatis 15 Iohannes

testimonium perhibet de ipso et clamat dicens hic erat quem dixi vobis

qui post me venturus est ante me factus est quia prior me erat 16 et de

plenitudine eius nos omnes accepimus et gratiam pro gratia 17 quia lex

per Mosen data est gratia et veritas per Iesum Christum facta est 18 Deum

nemo vidit umquam unigenitus Filius qui est in sinu Patris ipse enarravit |

1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word

was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God. 3 All things came into being

through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come

into being 4 in him was life, and the life was the light of all people.

5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

6 There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. 7 He came as a witness

to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. 8 He himself

was not the light, but he came to testify to the light. 9 The true light,

which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world. 10 He was in the

world, and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not

know him. 11 He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept

him. 12 But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave

power to become children of God, 13 who were born, not of blood or of the

will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God.

14 And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory,

the glory as of a father's only son, full of grace and truth. 15 (John

testified to him and cried out, "This was he of whom I said, "He who comes

after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me.' ") 16 From his fullness

we have all received, grace upon grace. 17 The law indeed was given through

Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. 18 No one has ever seen

God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father's heart, who has

made him known. |

3.3.2

The challenges to the Vulgate in the Protestant

Reformation

---When

Martin Luther began his "protests" against the abuses of the leadership

of the Roman Catholic Church in the early 1500s, one of his driving motives

was the life changing experience he had undergone through intensive study

of the Bible, and in particular, the letters of Romans and Galatians.

---When

Martin Luther began his "protests" against the abuses of the leadership

of the Roman Catholic Church in the early 1500s, one of his driving motives

was the life changing experience he had undergone through intensive study

of the Bible, and in particular, the letters of Romans and Galatians.

From

1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, the books of Hebrews, Romans

and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to understand

terms such as penance and righteousness in new ways. He began to teach

that salvation is a gift of God's grace through Christ received by faith

alone.[23]

The first and chief article is this, Luther wrote, "Jesus Christ, our God

and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification

... herefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us...Nothing

of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth

and everything else falls."[24]

("Martin Luther," Wikipedia

Encyclopedia)

As a university lecturer on biblical materials,

he found himself immersed in the study of the Bible. Also, haunted by his

personal uncertainty about his own salvation, this study -- at the advice

of his superior, Johann von Staupitz -- focused on the theme of Christ.

This study and the teaching especially of Romans and Galatians brought

him to a conversion experience. Increasingly, Luther realized the church's

teachings and practices were contradicted by scripture. He began lecturing

about

this and came increasingly into trouble with the Vatican. When Luther finally

broke completely with the Catholic Church in the 1520s after being excommunicated,

one of the ways Luther determined to use to spread his teachings was through

translating the Bible into the everyday German language of that day. The

complete Luther Bibel was released in 1534.

But his translation, although helping

to greatly diminish the use of the Vulgate in the emerging Lutheran churches

in central and northern Europe, was none the less dependent on the Vulgate.

For example, Luther had depended on the Greek Textus

Receptus that had come from Erasmus, but he also was careful to not

depart too far from the Vulgate as well. He consulted the Vulgate heavily

in doing his German translation. This "love/hate" relationship with the

Vulgate by Protestants would continue well into the 1800s. Long after the

Vulgate -- in public eyes -- had become the Bible of Roman Catholics and

Protestants had their own Bible in their particular native language, the

influence of the Vulgate would continue to be felt in these translations.

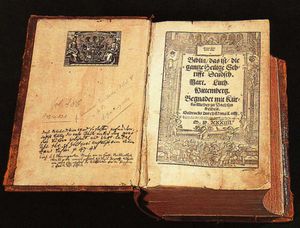

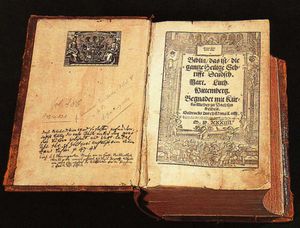

| Die Luther Bibel |

|

Over time he developed the idea of the

central role of scripture as the sole foundation for determining what Christians

should believe and how they should live. Called in the Latin

sola

scriptura, this principle gradually became adopted by all the Protestant

reformers, and has served as a central stance among Protestants until this

day. Thus Luther's renewed emphasis upon the Bible both through translation

and about its importance presented a growing challenge to the Latin Vulgate.

The translation of the scriptures into the "vernacular"

language of that time and region shifted the emphasis to the people having

a Bible in their own language so that they could read and understand it

for themselves. Increasingly, the Vulgate was associated with the Roman

Catholic Church. Protestants in general did what ever they could to distance

themselves from the Roman Church. Bible translation helped accomplish that.

The other

early reformers such as John

Calvin--- and Huldrych Zwingli---

and Huldrych Zwingli--- followed Luther's example with a strong emphasis upon the scriptures and

interpreting them to the masses of the people. Consequently, the Protestant

Reformation began the path to the identification of the Vulgate solely

with the Roman Catholic Church. For Protestantism the study of the scriptures

increasingly in the original biblical languages and then translating them

into the vernacular language has become one of the distinguishing marks

of this movement.

followed Luther's example with a strong emphasis upon the scriptures and

interpreting them to the masses of the people. Consequently, the Protestant

Reformation began the path to the identification of the Vulgate solely

with the Roman Catholic Church. For Protestantism the study of the scriptures

increasingly in the original biblical languages and then translating them

into the vernacular language has become one of the distinguishing marks

of this movement.

3.3.3

How Gutenberg changed the Bible

---Another

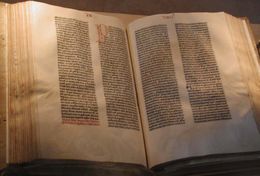

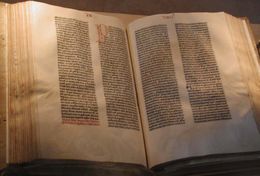

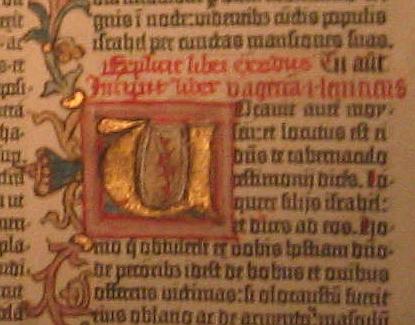

factor helping to place greater emphasis upon the Bible and its importance

for Christians generally was the invention of the printing press by Johannes

Gutenberg in 1447. He produced the first printed copy of the

Vulgate in 1455, and subsequently it is known as the Gutenberg

Bible.

---Another

factor helping to place greater emphasis upon the Bible and its importance

for Christians generally was the invention of the printing press by Johannes

Gutenberg in 1447. He produced the first printed copy of the

Vulgate in 1455, and subsequently it is known as the Gutenberg

Bible.

-----

----- ----Of

the appx. 180 copies first printed, several still exist in libraries scattered

around the world. The mass production of the Bible for a fraction of the

cost of the hand copied scriptures forever changed not only western culture

but the use of the Christian Bible as well. Books could now be produced

in large quantities and at very reasonable prices for that era. Consequently,

the distribution of the Bible expanded dramatically all across Europe.

When Luther released his translation of the Bible in German half a century

later, he took advantage of the printing press and mass produced it for

rapid distribution all across the German speaking sections of Europe. Thus,

before the Vatican could have time to stamp out Luther's movement, it spread

dramatically through the use of the printing press. Subsequently when other

translations of the Bible would be produced as time passed, the printing

press made it possible to print large quantities for wide distribution.

Increasingly, this made it possible for individuals to own their own copy

of the Bible. Previously, a single copy of the Bible could be found at

most of the churches. But only rarely would individuals own their own copy.

The printing press forever changed that. The Protestant emphasis on the

central role of scripture for Christian belief and practice was enhanced

by the availability of the scriptures for personal study.

----Of

the appx. 180 copies first printed, several still exist in libraries scattered

around the world. The mass production of the Bible for a fraction of the

cost of the hand copied scriptures forever changed not only western culture

but the use of the Christian Bible as well. Books could now be produced

in large quantities and at very reasonable prices for that era. Consequently,

the distribution of the Bible expanded dramatically all across Europe.

When Luther released his translation of the Bible in German half a century

later, he took advantage of the printing press and mass produced it for

rapid distribution all across the German speaking sections of Europe. Thus,

before the Vatican could have time to stamp out Luther's movement, it spread

dramatically through the use of the printing press. Subsequently when other

translations of the Bible would be produced as time passed, the printing

press made it possible to print large quantities for wide distribution.

Increasingly, this made it possible for individuals to own their own copy

of the Bible. Previously, a single copy of the Bible could be found at

most of the churches. But only rarely would individuals own their own copy.

The printing press forever changed that. The Protestant emphasis on the

central role of scripture for Christian belief and practice was enhanced

by the availability of the scriptures for personal study.

Bibliography

How do I learn

more about this?

Online:

Ancient

Methods of Writing and Copying

The Encyclopedia

of New Testament Textual Criticism, "Ancient Writing Materials": http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/WritingMaterials.html

"Ancient Writing":

http://dreamwater.org/bccox/writing.html

The University

of Michigan Papyrus Collection, "Learning About Papyrology : Ancient

Writing Materials":

http://www.lib.umich.edu/pap/k12/materials/materials.html

The Encyclopedia

of New Testament Textual Criticism, "Books and Book Making" : http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/BookMaking.html

Google search

of books in print treating ancient writing:

http://books.google.com/books?q=Ancient+Methods+of+Writing&ots=wjczpu5HGM&sa=X&oi=print&ct=title

Textual Criticism:

James R. Adair,

Jr. "Old and New in Textual Criticism: Similarities, Differences, and Prospects

for Cooperation":

http://rosetta.reltech.org/TC/vol01/Adair1996.html

Lengthy

article written for the SBL seminar presentation by a former student of

mine comparing similarities and differences between OT and NT Textual Criticism.

Wikipedia, "Textual

Criticism": http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textual_Criticism

General

article on the practice of copying ancient manuscripts of all kinds of

literature, including the OT, the NT, and classical writings.

Tony Seid, Interpreting Ancient Manuscripts:

http://www.earlham.edu/~seidti/iam/interp_mss.html

Very

helpful web site on Textual Criticism with numerous graphics illustrating

manuscripts and procedures.

New Testament

Textual Criticism:

New Testament

Gateway, "Textual Criticism": http://ntgateway.com/resource/textcrit.htm

The Encyclopedia

of New Testament Textual Criticism: http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/

Wikipedia, "Uncial": http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncials

Lorin Cranford, "Learning Textual Criticism,"

Cranfordville.com: http://cranfordville.com/g202TxtCritStdy.html#Wk1

Section

of fourth semester Greek studies, Greek 202, designed to introduce the

practice of textual criticism to students of biblical koine Greek.

Old Testament

Textual Criticism:

Old Testament

Textual Criticism: http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/OTCrit.html

Hebrew Old Testament,

"Textual Criticism": http://www.bible-researcher.com/links08.html

August Meek, "The

Old Testament," Catholic Encyclopedia: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14526a.htm

Article

traces the manuscript transmission of the text of the Old Testament.

Bruce K. Waltke,

"Aims of OT Textual Criticism," Westminster Theological Journal

51.1 (Spring 1989): 93-108:

http://www.biblicalstudies.org.uk/article_textual_waltke.html

Article

discusses what OT Textual Criticism hopes to accomplish by comparing various

objectives over the modern era.

The Latin Vulgate

The Encyclopedia

of New Testament Textual Criticism, "The Vulgate": http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/Versions.html#Vulgate

The Catholic

Encyclopedia, "Revision of the Vulgate": http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15515b.htm

Wikipedia, "Vulgate": http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgate

“Latin,” Wikipedia Encyclopedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin

“Bible Versions, Ancient,” The New Schaff-Herzog

Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge:

http://www.bible-researcher.com/schaff02.html

Martin Luther

"Martin Luther:

The Reluctant Revolutionary," Public Broadcasting Service: http://www.pbs.org/empires/martinluther/

"Martin Luther," Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_luther

Johannes Gutenberg

Wikipedia, "Johannes Gutenberg": http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Gutenberg

Wikipedia, "Gutenberg Bible": http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gutenberg_Bible

"Gutenberg: Man of the Millennium":

http://www.mainz.de/gutenberg/index.htm

Catholic Encylopedia, "Johann Gutenberg"

: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07090a.htm

Check the appropriate Bibliography

section in Cranfordville.com

---There

were many efforts to translate the Greek original documents into “old Latin”

but from

---There

were many efforts to translate the Greek original documents into “old Latin”

but from

---When

Martin Luther began his "protests" against the abuses of the leadership

of the Roman Catholic Church in the early 1500s, one of his driving motives

was the life changing experience he had undergone through intensive study

of the Bible, and in particular, the letters of Romans and Galatians.

---When

Martin Luther began his "protests" against the abuses of the leadership

of the Roman Catholic Church in the early 1500s, one of his driving motives

was the life changing experience he had undergone through intensive study

of the Bible, and in particular, the letters of Romans and Galatians.

and

and  followed Luther's example with a strong emphasis upon the scriptures and

interpreting them to the masses of the people. Consequently, the

followed Luther's example with a strong emphasis upon the scriptures and

interpreting them to the masses of the people. Consequently, the  ---Another

factor helping to place greater emphasis upon the Bible and its importance

for Christians generally was the invention of the printing press by

---Another

factor helping to place greater emphasis upon the Bible and its importance

for Christians generally was the invention of the printing press by  -----

----- ----Of

the appx. 180 copies first printed, several still exist in libraries scattered

around the world. The mass production of the Bible for a fraction of the

cost of the hand copied scriptures forever changed not only western culture

but the use of the Christian Bible as well. Books could now be produced

in large quantities and at very reasonable prices for that era. Consequently,

the distribution of the Bible expanded dramatically all across Europe.

When Luther released his translation of the Bible in German half a century

later, he took advantage of the printing press and mass produced it for

rapid distribution all across the German speaking sections of Europe. Thus,

before the Vatican could have time to stamp out Luther's movement, it spread

dramatically through the use of the printing press. Subsequently when other

translations of the Bible would be produced as time passed, the printing

press made it possible to print large quantities for wide distribution.

Increasingly, this made it possible for individuals to own their own copy

of the Bible. Previously, a single copy of the Bible could be found at

most of the churches. But only rarely would individuals own their own copy.

The printing press forever changed that. The Protestant emphasis on the

central role of scripture for Christian belief and practice was enhanced

by the availability of the scriptures for personal study.

----Of

the appx. 180 copies first printed, several still exist in libraries scattered

around the world. The mass production of the Bible for a fraction of the

cost of the hand copied scriptures forever changed not only western culture

but the use of the Christian Bible as well. Books could now be produced

in large quantities and at very reasonable prices for that era. Consequently,

the distribution of the Bible expanded dramatically all across Europe.

When Luther released his translation of the Bible in German half a century

later, he took advantage of the printing press and mass produced it for

rapid distribution all across the German speaking sections of Europe. Thus,

before the Vatican could have time to stamp out Luther's movement, it spread

dramatically through the use of the printing press. Subsequently when other

translations of the Bible would be produced as time passed, the printing

press made it possible to print large quantities for wide distribution.

Increasingly, this made it possible for individuals to own their own copy

of the Bible. Previously, a single copy of the Bible could be found at

most of the churches. But only rarely would individuals own their own copy.

The printing press forever changed that. The Protestant emphasis on the

central role of scripture for Christian belief and practice was enhanced

by the availability of the scriptures for personal study.